We’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

The scene looked like a combat zone. It was July 10, 2016. A wall of police officers dressed in riot gear lined East Boulevard at the corner of France Street in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Blair Imani and at least 100 other protesters stood opposite the officers in the front yard of Lisa Batiste, a resident who had invited the demonstrators onto her property for their safety.

What began that morning as a peaceful youth-led march to protest recent police killings of Black people had escalated into chaos.

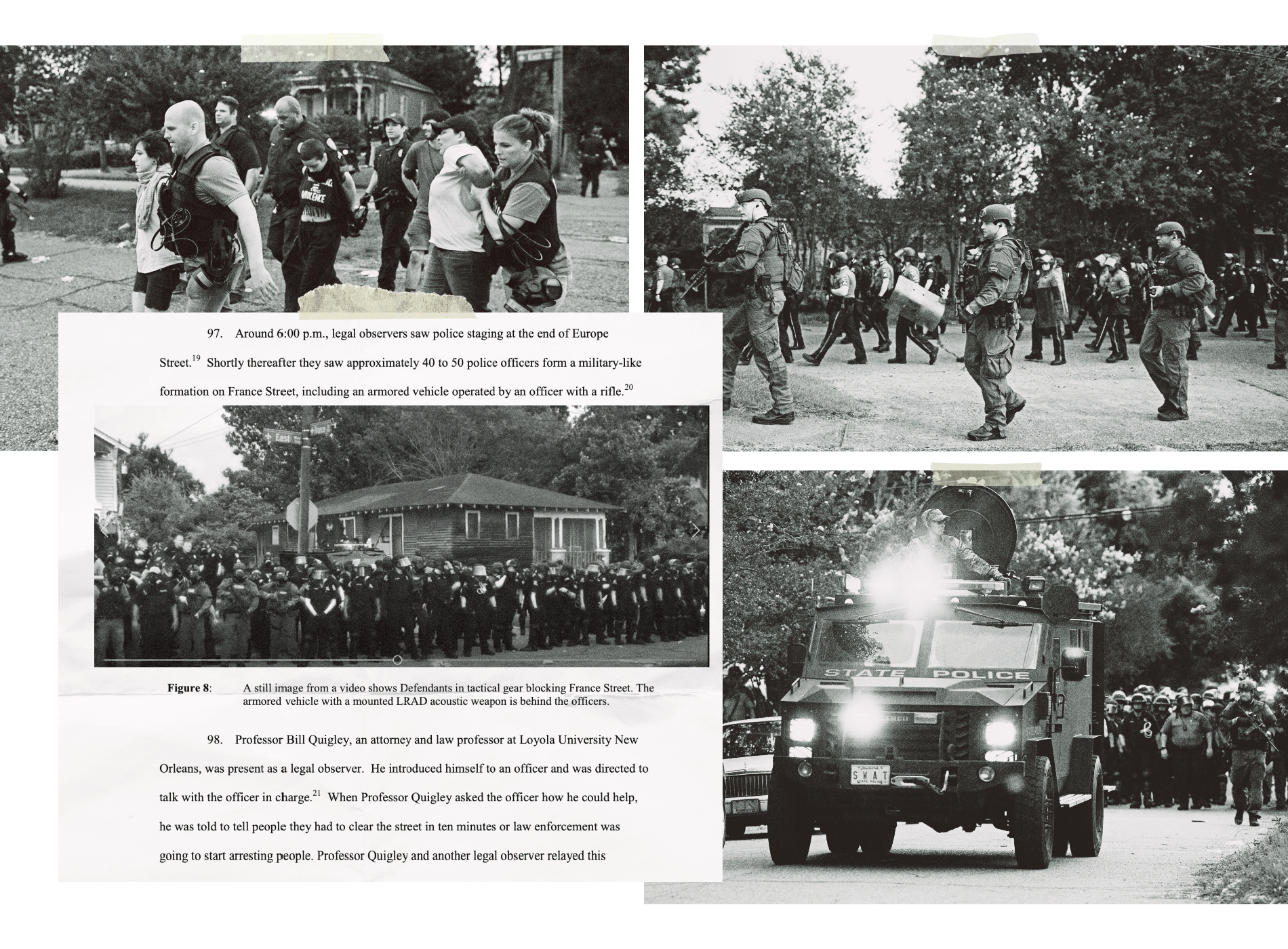

On that Sunday evening, Imani and the other protesters standing in Batiste’s yard were a short walk away from two houses of worship — Mt. Zion First Baptist Church to the north and St. Agnes Catholic Church to the south; yet Imani felt no sense of safety or salvation, only a rush of fear. Video taken by one protester showed lines of police blocking them on three sides. The officers ordered them to stay off the street and off the sidewalks. Any people they caught were arrested.

Directly behind the officers, Imani could see a SWAT vehicle with a large circular device fixed on top. She felt disoriented and overheated. What seemed to her like a four-hour standoff between the police and protesters she later learned was only about 60 minutes.

Imani did not know at the time that the circular machine on top of the SWAT vehicle was a long-range acoustic device (LRAD), developed for the military in response to the bombing of a U.S. warship off the coast of Yemen in 2000. The LRAD emits a high-pitch sound that can throw off balance, and cause nausea or permanent hearing loss at close range.

Nadia Salazar Sandi, another protester in Batiste’s yard, had seen her fair share of protests working as a grassroots organizer; however, she did not expect the level of aggression she saw from police that day.

“I was a police liaison in my work,” Sandi told The 19th. “I could have talked to cops all day and all night because I was trained to help de-escalate situations. But I remember seeing the look in their eyes. They were not willing to negotiate.”

After standing in the yard for some time, Sandi and a number of others tried to run from the center of the conflict. Sandi, who was 24 years old at the time, said she then remembers the weight of a person tackling her to the ground. MSNBC video of Sandi’s arrest showed an officer pulling her back-first onto the asphalt street. Two other officers quickly flipped Sandi onto her stomach and fastened her wrists behind her back with a zip tie.

“They came for blood,” said Sandi, who moved to the United States from Bolivia when she was 10 years old.

The clash with police that day gained national media attention and resulted in multiple lawsuits against law enforcement. Imani and Sandi joined 12 other plaintiffs, a group of mostly women and LGBTQ+ people, to sue the City of Baton Rouge, members of the Baton Rouge Police Department and the Louisiana State Police in 2017. After years of waiting and uncertainty, the city held a civil trial in February that concluded with the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Council approving a $1.17 million settlement, offering the plaintiffs some closure to the ordeal.

The Black Lives Matter protests at that time represented a new multiracial and multicultural movement that brought more visibility to the leadership of women and LGBTQ+ people in activism. The Baton Rouge lawsuit is one example of how these groups are pushing for government accountability through a combination of direct action, political advocacy and legal cases.

But the memories of that day still haunt the four plaintiffs who spoke with The 19th about their arrests at the Baton Rouge protest nearly seven years ago. And the court case brought that front and center.

“It was the most terrifying, traumatizing experience of my life,” Imani said. “So having to be in court for those two weeks was very stressful. It was just like reliving that from every angle.”

The summer of 2016 felt heavy under the weight of heightened political tension in the United States. Far-right and white nationalist groups looked to Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy as an opportunity to disseminate their rhetoric to a mainstream audience. The Pulse nightclub shooting that targeted LGBTQ+ people in June became the country’s deadliest mass shooting by an individual in history — until the following year.

And the Black Lives Matter movement received international attention, bringing more public and political awareness to racism in U.S. policing, mass incarceration and the legal system at large.

While Black women and queer people have always been key figures in movements throughout the country’s history, they gained broader recognition as leaders of Black Lives Matter. Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza and Ayọ Tometi (formerly Opal Tometi), two of whom publicly identify as queer, formed the Black Lives Matter Network in 2013 following the killing of Trayvon Martin.

The network grew larger and more politically influential after national uprisings in response to the 2014 killings of Eric Garner, Michael Brown and Tamir Rice. Though the stories of Black men and boys have received widespread attention, highlighting violence against Black women and LGBTQ+ people is at the core of the movement. This includes the death of Sandra Bland in 2015 and the subsequent #SayHerName campaign.

These efforts attracted support from people of different races and cultural backgrounds, many of whom were motivated to become activists for the first time. Despite reports of disagreements between national Black Lives Matter figures and grassroots organizers, Black women and queer people have remained engaged on criminal legal issues at the local level.

“Black women have certainly been key figures in the struggle to end police violence. They’ve taken the lead in finding alternative routes to obtaining justice and trying to achieve systemic change due to the inability of the criminal legal system to administer punishment in cases of police shootings,” said Jennifer Cobbina-Dungy, an associate professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Michigan State University.

Evidence of those women-led roots were on display in Baton Rouge in 2016 as they stood on the front lines to protest the July 5 fatal police shooting of local resident Alton Sterling. Sterling’s death was followed quickly by another: The next day in Minnesota, Philando Castile was fatally shot by the police in the presence of his girlfriend and 4-year-old daughter.

The demonstrations in Baton Rouge produced a Pulitzer Prize-nominated photo capturing the militarized police response. In the image, Ieshia Evans, a Black, 35-year-old nurse, stands calm and resolute in a long, flowing dress and ballet flats, arms crossed in front of her as two police officers in riot gear rush toward her.

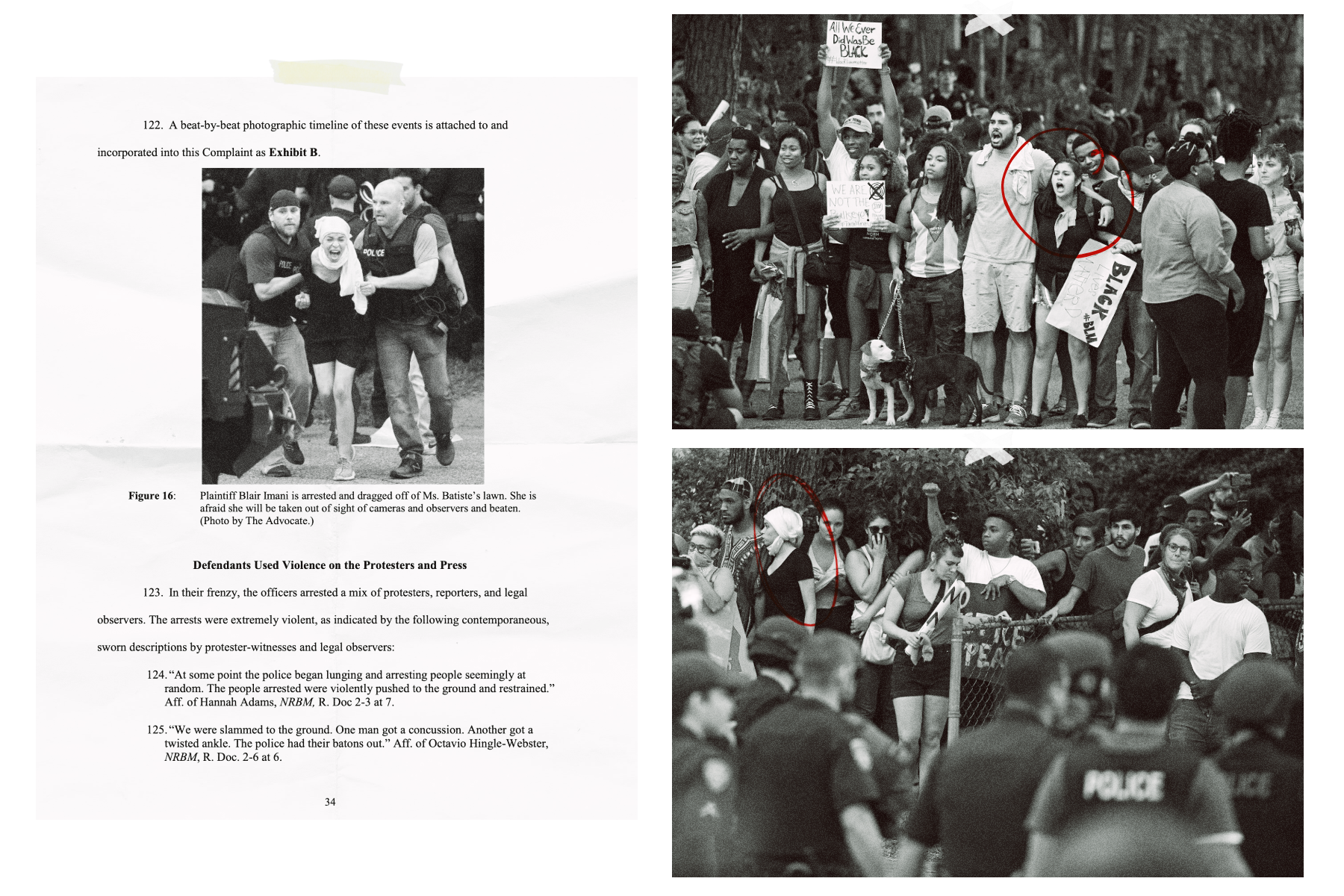

The day after this viral photo, on July 10, Imani became the subject of another striking picture. Two officers are seen holding Imani’s arms back while she lets out a scream that seems to break through the image.

Right: Images of protesters prior to the arrests on July 10, 2017 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Imani and Sandi are circled in red in both images. (The 19th; Max Becherer/AP)

“When I was finally grabbed by the police, I heard one of them say, ‘Really give it to her,’ and I just started screaming because I literally thought they were going to kick my ass or something,” said Imani, who was 22 at the time of her arrest. As a Black, queer Muslim woman who studied history at Louisiana State University, Imani thought in that moment about Bloody Sunday in 1965 and the violent police clashes in the decades since.

About a block away, Karen Savage, a journalist and one of two reporters in the lawsuit, had been photographing and filming the conflict. As she looked for a way out to safety, she was mindful to keep her camera rolling, she told The 19th. Savage could see nearby protesters’ mouths open wide as they screamed, the sounds of their voices absorbed by the shrieking LRAD.

She started to notice police attention on her as she kept walking and recording. “They looked like soldiers,” she recalled. Then she felt them following her. Savage walked through a parking lot toward a McDonald’s, but an officer grabbed her before she could make it to the restaurant door.

Savage said she identified herself and told the officer where he could find her credentials, but that only made him angrier. With her wrists zip tied behind her back, Savage said she could feel her hand throbbing in pain at the tightness.

“I remember telling the officer that I felt pain,” Savage said. “I felt like shooting pain in my arm, like I thought I was having a heart attack. I asked if he could please fix it, but he pulled it tighter.”

That day, Savage, Imani, Sandi and dozens of others were arrested and taken to the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison eight miles away. They were charged with “obstructing a public passageway” or “obstruction of a highway” and “resisting arrest,” but these were later dropped.

Among those arrested was then-17-year-old Alexus Cheney (now Alexus Swope) and her mother, Tammy Cheney. The family intended for the Baton Rouge protest to be a short stop on a road trip from their home in Florida to historic sites around the country with Swope’s then-5-year-old brother and their dog.

Swope is White, and had never protested before that year, but when she saw the news of the police shootings of Sterling and Castile, she looked for local youth-led demonstrations and asked her mother if they could go. A march in New Orleans was her first protest ever. She described it as the “most amazing experience,” filled with unity and mutual support. Her second protest in Baton Rouge a couple of days later was a different experience entirely.

Swope told The 19th that the day started off great, like the New Orleans demonstration, but the police presence and aggression escalated as the march was winding down. Swope’s family decided to leave, but could not find a way around the police roadblocks, she said. Parked at an intersection about a block from the yard where other protesters were gathered, Swope’s mother stepped away briefly to assess the situation around them.

(The 19th; Max Becherer/AP)

Three officers then approached Swope at the car with her brother inside and arrested her. Video from Swope’s mother’s cell phone shows Cheney running back to the car as nearby protesters chant “Let her go!”

Back at the car Cheney asks the officers why they took her daughter. After Cheney questions them several times, the officers are seen arresting her as well.

At the adult prison, teenage Swope, along with the others, had to strip down naked, bend over and cough as part of the search. “I’ve never had to be naked in front of that many people against my will before,” she said “So I tried to dissociate, focus outwards, and not on anybody or anything just to get through it.”

Swope was released from prison at 5 p.m. the next day and her mother joined her around midnight. However, her brother had been taken by child protective services and their dog taken to animal control. The family was reunited two days later after a court appearance during which the judge dismissed the case.

Ultimately, Savage, Imani and Sandi were all released by Monday, July 11, and the turbulence of the previous hours began to settle. They each returned to their lives to sit with the reality of what happened to them — and the question of what to do next.

The idea of suing a major city and its police department was nerve-wracking, Sandi and Imani said, particularly when police were telling the media in the days after that the protesters had been acting violently.

One week after their arrests, a man shot six police officers in Baton Rouge, killing three of them and hospitalizing the others. Imani helped organize a community vigil for the officers, which received praise from the late Democratic U.S. Rep. John Lewis of Georgia.

The shooting added a new level of tragedy and tension, but those arrested on July 10 still wanted to see accountability from the police department and the city. By July 2017 the 14 plaintiffs had filed their legal complaint, represented by longtime civil rights attorneys John Adcock and William Most.

Their suit argued that the police had violated their 1st, 4th and 14th Amendments of free speech, protection from excessive force and the right to a fair judicial process. But the court process moved slowly over six years. In that time the plaintiffs wrestled with the emotional and legal aftermath of their arrests. Sandi said she was strongly triggered by any police presence to the point that she could not do organizing work. She hopped from job to job and struggled to find stable work for years. The arrest record did not help.

In the years leading up to the trial, Imani gained an online following of hundreds of thousands, using her platform to educate and raise awareness about racial justice, gender and cultural issues. But she remained unsettled and fearful after her experience in Baton Rouge, a place she previously loved and had spent her college days, but could not return to for years.

“I wanted to become a public figure because I felt like if I was more visible, then I would be safer. That is arguable, but it is one of the things that I thought. I also felt like if I had my own platform, then I could correct the story the police were telling,” Imani said.

Savage said she fixated on her role as a journalist and tried to take herself out of the narrative. As an older White woman, Savage added that she also felt her trauma in Baton Rouge did not compare to what many others throughout the country experience regularly.

Swope tried to remain politically active after her arrest by organizing another demonstration in hometown Naples, Florida. Animosity from residents in her conservative community — including family that stopped speaking to her — eventually made her afraid to speak out.

The long-term emotional and psychological effects experienced by plaintiffs in the Baton Rouge case are not unusual for protesters over the last decade, Cobbina-Dungy said. Those associated with Black Lives Matter protests in particular have encountered similar levels of aggression from law enforcement in Ferguson, Missouri; New York City; Los Angeles; and Washington, D.C.

As a result, some, like Sandi, step away from activism that involves direct contact with police and instead may choose other forms of civil or political engagement, Cobbina-Dungy said.

As the years went by, the plaintiffs questioned whether anything would come from their lawsuit. Then, in February, the trial began. It offered a chance for them to get the accountability they wanted, but threatened to undo the work they had done to heal emotionally.

“The first day that I went in and sat down, within the first 10 minutes, I was already completely broken down in tears,” said Swope, who is now 24 years old. “I don’t think I was expecting how emotionally charged things would be. Even though I read papers and documentation on the evidence, I didn’t know how much video they had.”

But Most’s legal team chose to keep their arguments focused on the officer’s conduct — documented by video and photos — and rather than the emotional harm caused by the arrests.

One argument from the plaintiffs was the prolonged use of the LRAD machine, which the department borrowed from the state police without properly training their officers, Most told The 19th. A representative of the police department said in court that they were “messing around” with the machine when using it against the protesters.

In recent years police have used LRADs as a tool for crowd control during protests, highlighting the decades-long militarization of U.S. police forces. Since the 1990s, dozens of U.S. police departments have participated in exchange programs with Israeli police to learn about counterterrorism, which has included briefings with members of the Israeli military.

Local police departments also receive billions of dollars in surplus military equipment like armored vehicles and high-powered guns thanks to a federal program established in the 1990s. Access to this has expanded in recent decades and gives departments a lot of discretion, said Karen Pita Loor, a clinical professor of law with Boston University who is not affiliated with the Baton Rouge case.

“There is no requirement to undergo any particular type of training before a department receives or uses these weapons. That’s why it’s terrifying but not surprising when you hear that police officers are not trained on how to use them,” Loor said.

The trial also revealed other notable details about the police’s approach to the protests. In general following an arrest, police must submit a warrant from a judge or an affidavit of probable cause listing the alleged crimes. Most’s team learned that instead of writing these affidavits after the arrests, as expected, the officers had written them with the list of alleged crimes before the protest happened. One officer testified at trial that his name had been forged on an affidavit.

Another striking moment for Most came when officers invoked the Fifth Amendment during trial to avoid incriminating themselves. “It’s an acknowledgement that there’s the potential risk of criminal prosecution for what the police did,” Most said.

The Baton Rouge Parish Attorney’s Office did not return The 19th’s requests for comment about the case, but during the trial lawyers for the city argued that protesters ignored orders to disperse.

The city’s settlement of $1.17 million is one in a long list of police settlements around the country. A March 2022 report from The Washington Post analyzing data from the country’s 25 largest police and sheriff departments found that they collectively spent more than $3.2 billion in settlement payouts within the last decade. Claims against them ranged from illegal search and seizure to excessive use of force.

Beyond the money, the plaintiffs said they hoped to see written changes in policy and practices from the department. These were not included in the settlement and the city would not commit to policy changes. Most said so far there has not been evidence of any policy changes, but he hopes the lawsuit and settlement will be a deterrent from future misconduct.

Sandi said that money can be a powerful incentive for government institutions to make changes, but she recognizes that substantive change is a slow process. She, like thousands of others around the country, witnessed the televised scenes from the 2020 protests against the police killing of George Floyd. She saw the reports of rubber bullet injuries and other instances of police brutality, four years after she experienced her own.

More than anything, Sandi said she wants the Baton Rouge settlement to send a message to other activists that they have rights and can fight back in court. She also hopes the settlement can serve as legal precedence in future lawsuits.

Sandi now works as an organizing director for a labor advocacy group in Washington, D.C. Her family and community have been big support systems during the difficult years after her arrest. She also reconnected with Bolivian folkloric dancing, Caporales, which she said helped her regain a sense of power over her body that was taken that July day.

“I feel myself healing,” Sandi said. “I felt like this lawsuit was an impediment. I felt like I couldn’t move on or fully heal without there being a resolution and answer.”