This AAPI Heritage Month, we’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

In 1998 Susan Oki Mollway was surprised to make history when she became a federal judge. Growing up in Hawaii, Mollway was accustomed to seeing Asian people, particularly those of Japanese descent like herself, in positions of power in state and local government.

Mollway was the first Asian-American woman to become an Article III judge. Judges on Article III courts are nominated by presidents and confirmed by the U.S. Senate; they include judges on the U.S. Supreme Court, federal courts of appeals, federal district courts and the U.S. Court of International Trade. Prior to Mollway’s appointment by President Bill Clinton to the U.S. District Court for the District of Hawaii, just 11 of the previous 2,840 Article III judges were Asian American, and all 11 were men.

It would be another decade before a second Asian-American woman, Kiyo A. Matsumoto, followed Mollway to the federal bench.

Since that time the number of Asian-American women represented in federal court has surged in recent years. To date, 29 total women have been nominated and confirmed to sit on Article III courts. In his first two years, President Joe Biden appointed 12 Asian-American women, two more than the 10 appointed by President Barack Obama in eight years and more than double the number appointed during President Donald Trump’s four years in office.

Among these judges are Neomi Rao, a Trump nominee, and Florence Pan, a Biden nominee, who both sit on the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, a stepping stone for the U.S. Supreme Court, where Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson once sat.

The increased pace of Asian-American women appointed to judgeships reflects the growth of Asian Americans as a demographic and as a political influence.

“President Biden appointed five Asian-American women to the circuit courts and has nominated or has appointed more Asian-American women to the bench than than any president in history,” said Chris Kang, cofounder and chief counsel of the progressive judicial advocacy group Demand Justice.

The latest wave of appointments is in many ways the long-term fruit of work by Kang and other advocates. In “The First Fifteen: How Asian American Women Became Federal Judges,” Mollway’s 2021 book about her journey to the judiciary, she notes Kang’s efforts to expand judicial diversity broadly during his years working in the U.S. Senate and the White House during the Obama administration. He and others also actively supported Asian-American women judicial nominees throughout the process, Mollway wrote.

Historically Asian-American women have faced a variety of challenges that can affect their advancement in the legal profession and ability to receive a federal judicial appointment. These challenges can come from cultural and gender expectations as well as institutional barriers, said Democratic Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawaii, who is the first Asian-American woman senator and currently sits on the Senate Judiciary Committee.

AAPI Heritage Month: Our legacies, our experiences, our future

This story is part of our AAPI Heritage Month coverage. From recommended reading to staff reflections and historical data, we’re focused on telling stories highlighting the past, present and future. Explore our work.

“I think it has to do with both our own aggressiveness in pursuing the jobs and people's expectations,” Hirono told The 19th. “Growing up I was really curious to be vocal or aggressive … so I encourage AAPI women to use their voices more in whatever place they are at.”

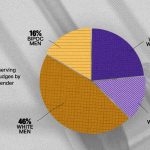

The pipeline problems for Asian-American women in the judiciary begin with the underrepresentation of Asian-Americans among lawyers more broadly. The American Bar Association’s 2020 profile of the legal profession determined that 86 percent of U.S. lawyers are non-Hispanic White people. Two percent of U.S. lawyers are Asian, even though Asian people represent 5.9 percent of the country’s population. A study from 2022 found that Asian and Native American women received the least amount of business from corporations hiring outside legal counsel.

To be considered for a federal judicial appointment, Asian women often have to move beyond their law firms or companies to navigate the political dynamics of getting the attention of a senator or the president.

“Our courts were predominantly White male corporate partners and prosecutors. … Many of them are in these so-called ‘elite’ legal circles where they would get on the radar of a senator or the president to even be considered for a nomination,” Kang told The 19th. “When you start looking at a broader range of experiences — not only race and gender and sexual orientation, but also professional experience — you're starting to look at a much wider range of candidates who traditionally had been excluded.”

Like Kang, a number of lawmakers and organizations work behind the scenes to help expand the scope of people considered for nominations. Mollway wrote that Democratic Sens. Daniel K. Inouye and Daniel Akala, both representing Hawaii at the time, included her name in their list of four names for potential nominees they recommended to Clinton.

“When I decided to seek a judgeship, being the first Asian woman Article III judge did not enter my mind,” Mollway wrote. “Not only did I lack any confidence I would actually be selected, but I had no thought that any Asian woman selected to fill the Hawaii vacancy might be the ‘first’ of anything in the nation.”

But others would follow. For years, the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (NAPABA) has taken advantage of members with powerful contacts to increase the number of strong potential nominees. The organization also helped prepare and walk nominees through the process, Priya Purandare, executive director of NAPABA, told The 19th. Current and former judges also serve as mentors for subsequent nominees and those interested in the process, she added.

“I don't think the process looks the same for any of them,” Purandare said. “It's a highly scrutinized, political process, and so I think that they do find a lot of comfort and support from each other.”

Mollway said in an interview with the Ninth Judicial Circuit Historical Society that she believes that as more Asian women gain seats on the judiciary, the current and former judges can play a key role in encouraging others to consider a judgeship.

Even as the number of Asian-American women judges and Asian-American judges generally rises, efforts to address systemic and cultural barriers continue. To this day a person of Asian descent has not held a U.S. Supreme Court seat. And those from East Asian background hold more judicial seats compared with South Asian people.

Purandare and Hirono said improving on current numbers will require thoughtful approaches at multiple levels of the legal industry.

“We need to get a lot more people in the pipeline everywhere at our law firms, and the judiciary and once you decide, and so it becomes intentional,” Hirono said. “Diversity doesn't happen because it sounds like a good thing or a good idea. You have to be intentional about it.”