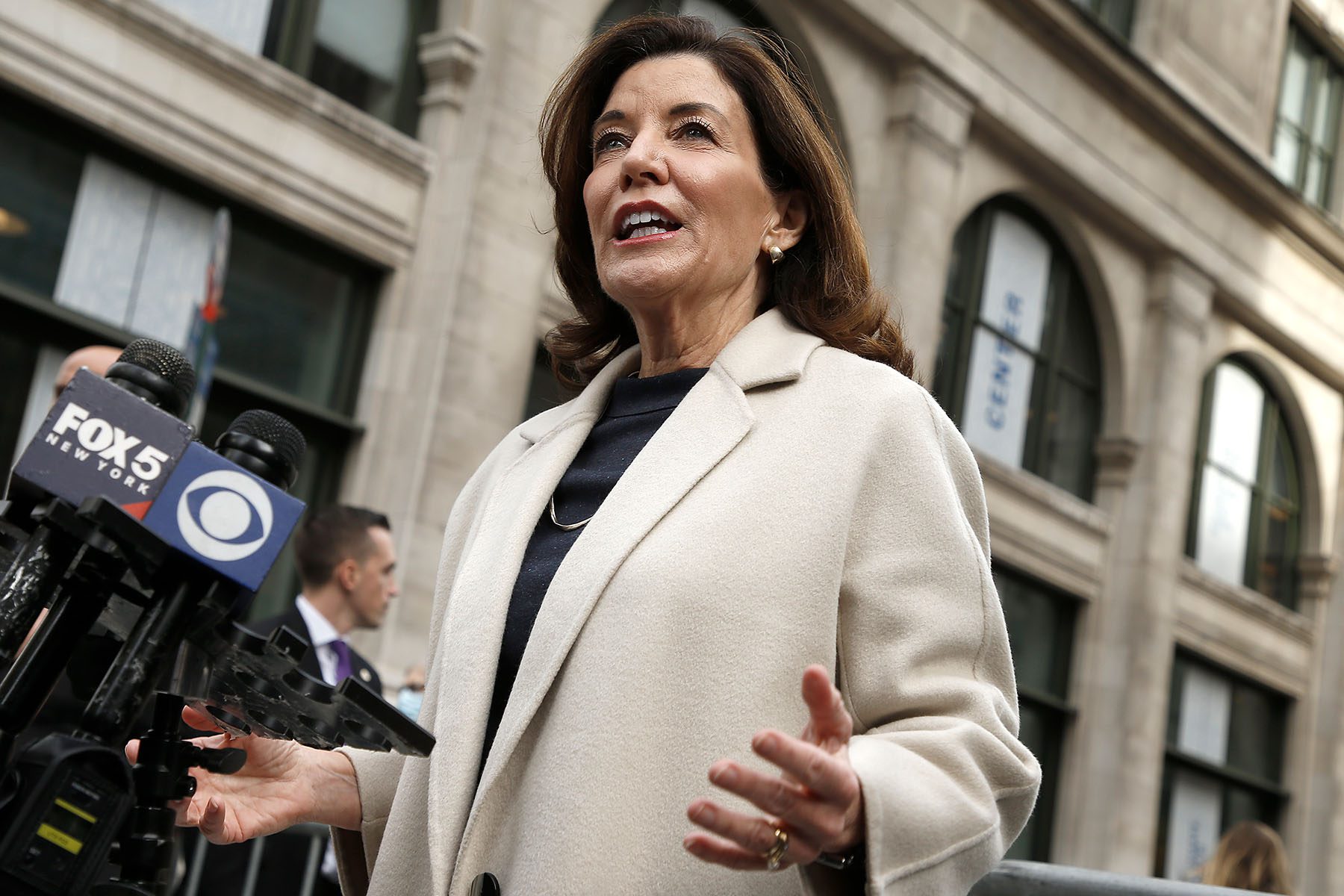

When New York Gov. Kathy Hochul announced last week that she would support legislative efforts to install term limits on statewide positions, including her own, she framed it as good governance.

“For government to work, those of us in power cannot continue to cling to it,” she said Wednesday during her first State of the State address.

Hochul was alluding, at least partially, to her disgraced predecessor, Andrew Cuomo, who as part of a political dynasty served as the state’s attorney general before he was elected to three consecutive terms as governor. Cuomo resigned last year as he was being investigated for sexual harassment and mismangement. He has largely denied wrongdoing.

But term limits may have an added benefit: increasing women’s political representation in New York.

“Term limits in and of itself sort of incentivize more women to run,” said Samantha Pettey, an assistant professor of political science at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts who studies the effects of term limits in statehouses. “So if more women are running right off the bat, then you already have a greater chance of a female being elected.”

Hochul, whose ascension from lieutenant governor made her New York’s first woman governor, wants a limit of two four-year terms for the offices of governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general and comptroller. She also proposed mostly banning those officials from receiving outside income while in office, another nod to Cuomo, who signed a multimillion-dollar book deal during his tenure. Hochul has proposed adding term limits through a constitutional amendment, which will require backing from lawmakers and voters over several years.

Research shows that incumbency overwhelmingly influences reelection. Since men have long held a majority of elected seats at all levels of government, it has effectively created a cycle of men incumbents in American politics that can be difficult for first-time women candidates to break. Forms of term limits — including limits to consecutive terms or a more restrictive lifetime ban — can help disrupt that.

“When it comes to incumbents, the majority of them tend to run and win,” said Rachelle Suissa, founder and president of Dare to Run, a national group that helps women run for all levels of office, including for seats in New York. “So if you’re a new candidate, whether you’re a woman or a man or a person of color, the reality is most likely you’re not going to win because the incumbent tends to win the race.”

In the Nevada legislature, term limits are partially responsible for recent gender parity gains, organizers said. The state has 12-year term limits for both chambers.

But term limits, which gained popularity in some statehouses in the 1990s, have historically produced a mixed bag when it comes to women’s political representation. A study published in 2006 concluded that term limits in statehouses had “virtually no effect on the types of people elected to office.” Some statehouses with term limits still remain male-dominated. Women overall only make up a little over 31 percent of legislatures.

And states with term limits on governors haven’t always fared better. Virginia, which prohibits its governors from running for two consecutive four-year terms, has never elected a woman. (Former Virginia Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe sought the office again last year and received more votes than two women primary challengers; he lost in the general election.)

Some recent examinations on the impact of statehouse term limits on policy making and demographics have reiterated previous findings. But Pettey challenged established assumptions about term limits’ effects on gender. She highlighted Nevada, and noted that a handful of other statehouses with higher representation of women in recent years, including Colorado, have term limits.

“I think a lot of the research is dated, and because term limits aren’t like the hot topic these days, there hasn’t been a lot of newer research on it,” she said.

The effect of term limits on statewide offices is less understood in part because there are fewer women in those roles compared to a statehouse, according to Pettey. Hochul is one of only nine women governors in the country — and one of four who first reached the position through succession rather than election.

It also may not take into account the evolution of women’s recruitment groups, which have prepared candidates when an elective seat opens up. Cynthia Richie Terrell is founder and executive director of RepresentWomen, which advocates for structural changes to help elect more women. She said more intentional organizing by such groups could be shifting what’s understood about what term limits could do for women’s representation.

“I see it as a reform whose time has come, in the sense that there are now groups that are ready to take advantage of those openings,” she said.

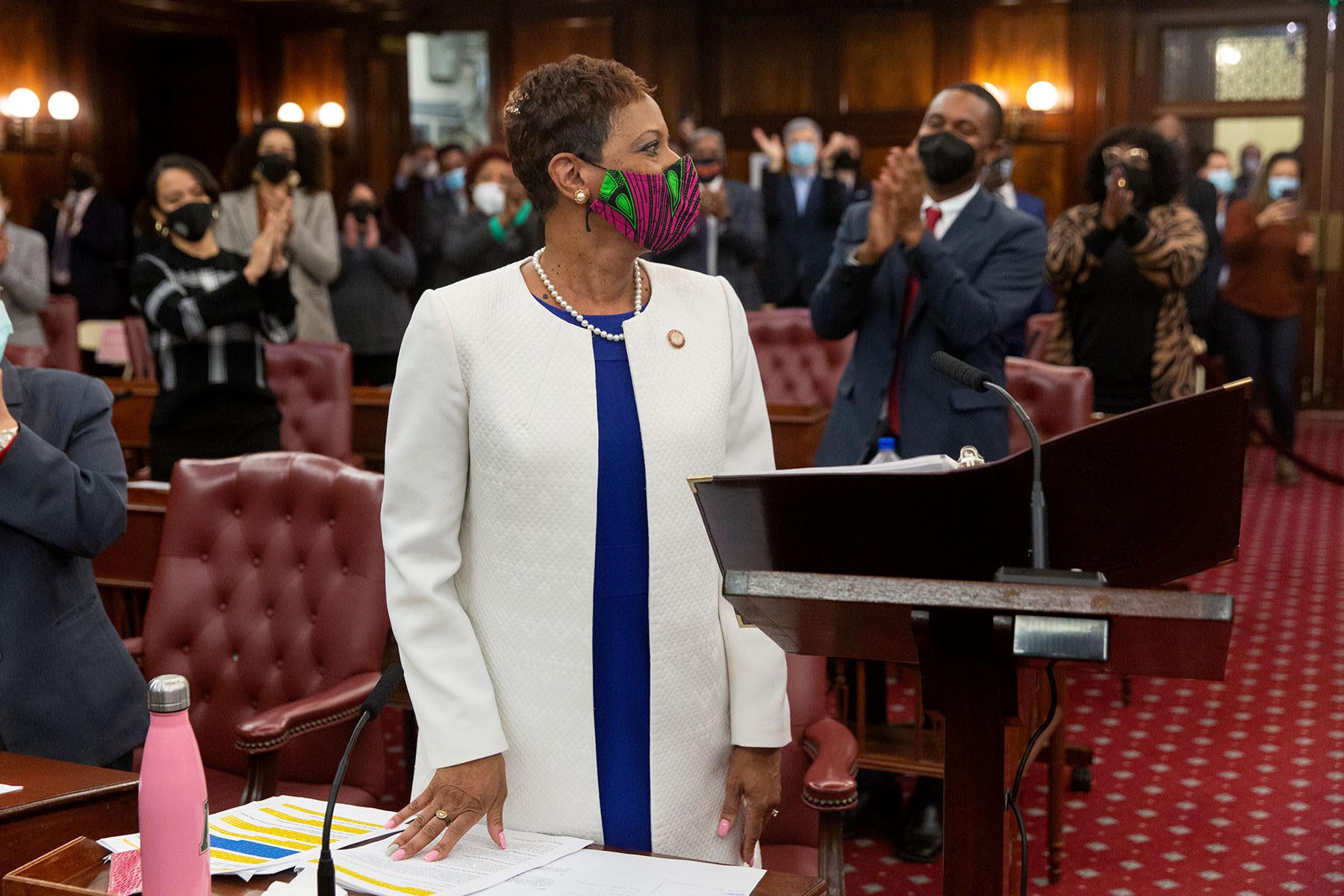

In New York City, where the new 51-member city council is women-majority for the first time ever, organizations like 21 in ‘21 intentionally focused their attention on races without incumbents. More than 30 council seats were open because of term limits.

“Open seats were the only places that we chose to play, because those were the places that we knew there was tremendous opportunity,” said Jessica Haller, executive director for the group.

Sophie Nir is executive director of Eleanor’s Legacy, which helps elect Democratic women in New York who support abortion. She applauded Hochul’s efforts, though noted in the end it will impact just a handful of offices, since term limits on legislative seats are not part of Hochul’s proposal. But Nir sees another potential benefit — a change away from what she described as “ego driven power hoarding” in statewide office in New York. That ultimately could make behind-the-scenes government work more welcoming to women.

“That will allow opportunities for a real shift in the culture of Albany,” she said. “The cultural shift is what will empower women.”

Michele L. Swers, a professor of American government at Georgetown University, said the real impact from open seats created by term limits is more contingent on society addressing longstanding barriers to women running and winning elective office. That includes supporting them financially in primaries and allowing them to use campaign funds for child care. Swers, who has extensively studied women’s political power in Congress, noted some policy proposals that suggest candidates use campaign funds for income or health insurance, since seeking a high-profile seat can greatly disrupt a person’s livelihood and wages. That disproportionately impacts women, women of color and people from marginalized communities.

“There’s a lot about campaign infrastructure that favors people who have money or connections to different types of political advisors that help them run a campaign,” she said.

It’s unclear if Hochul’s proposal will get enough support to advance through the legislature. Political leaders have so far offered a mixed response, and its chances could hinge on Hochul’s own election bid.

But Haller noted the necessity of jumpstarting these structural conversations. She pointed to research that shows it will take the United States at least 200 years to reach gender parity.

“We need to disrupt the rate of change,” she said. “And that’s what 21 in ‘21 did. And the only way to do that is with something like a lot of open seats, which comes with term limits.”