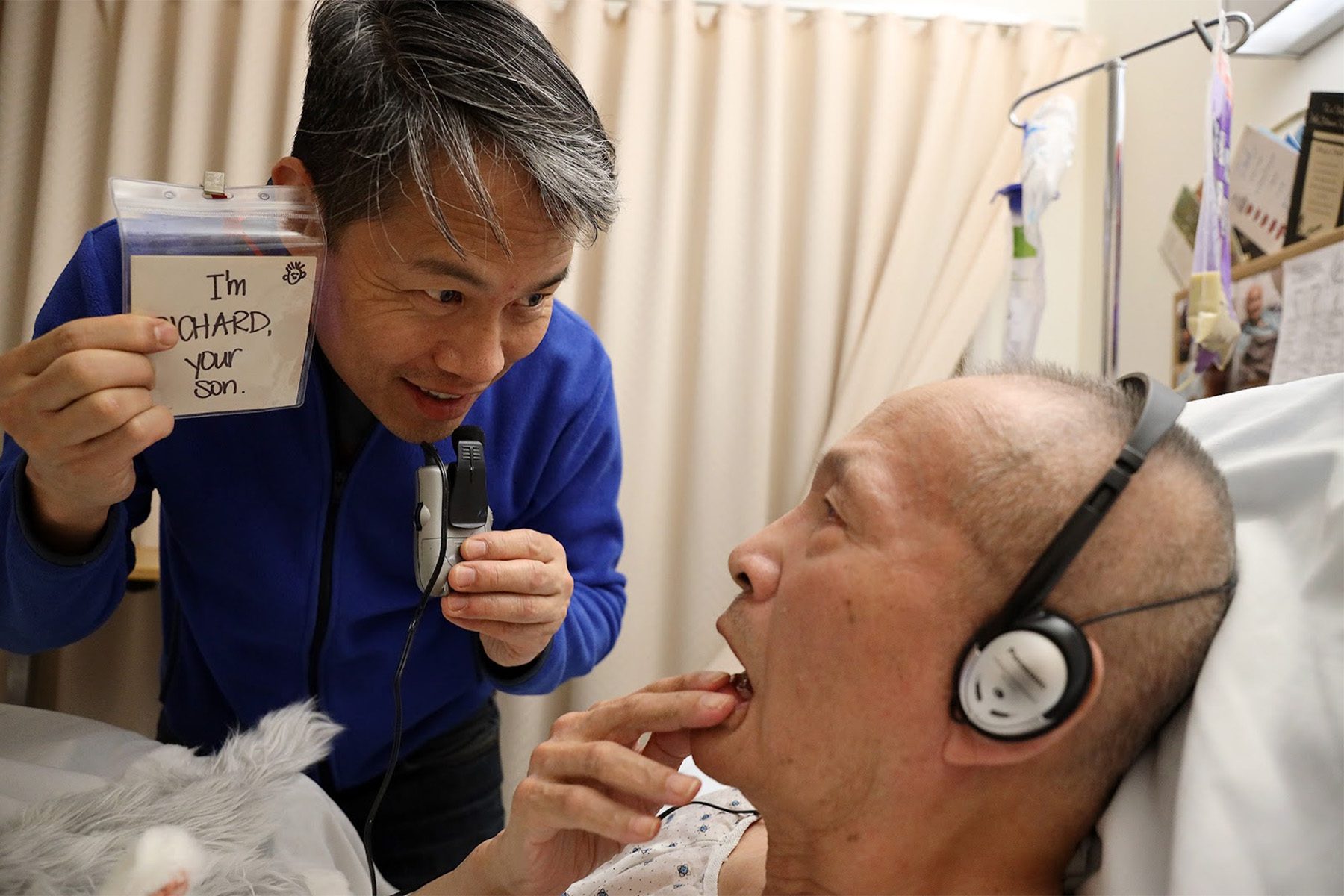

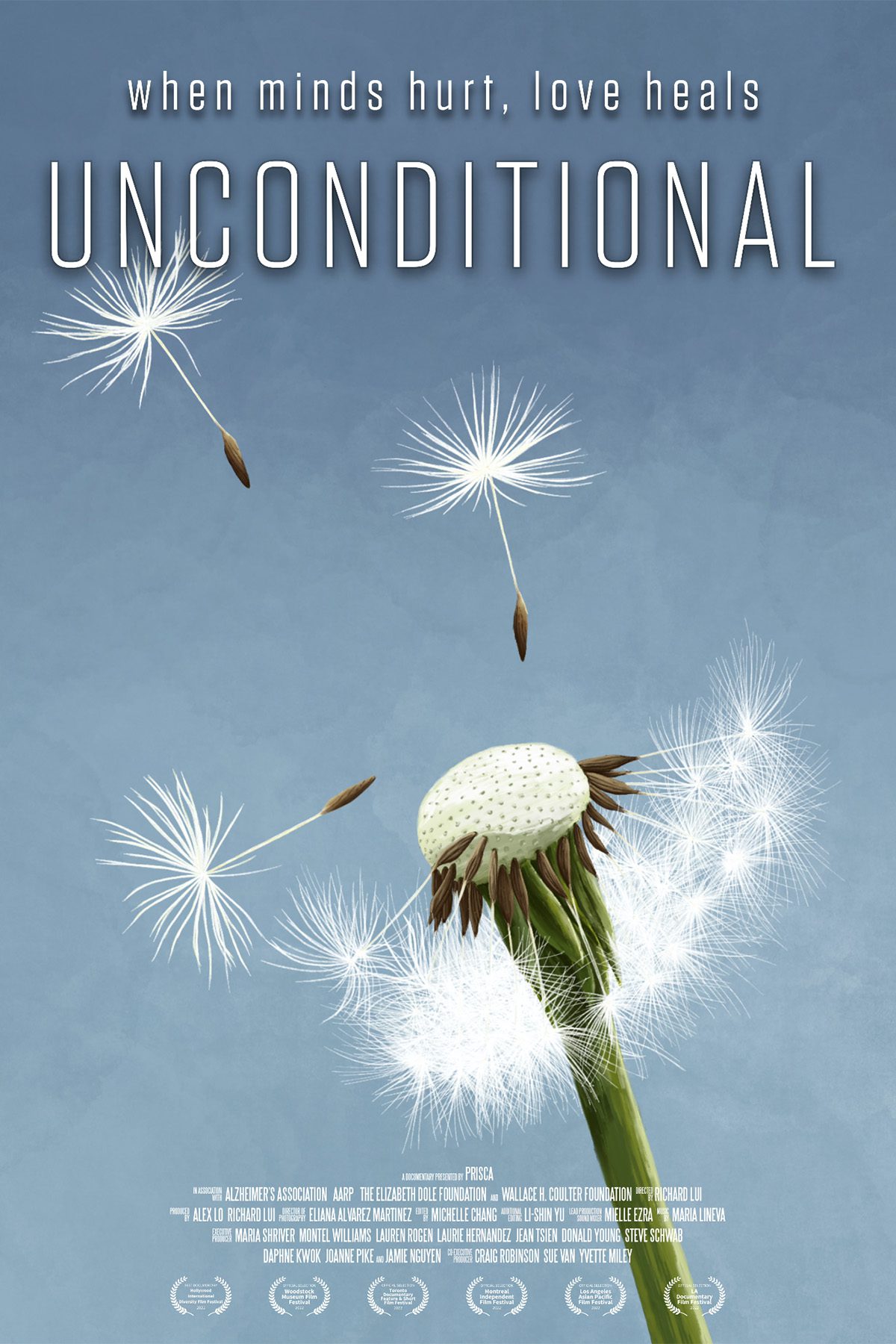

TV news anchor Richard Lui’s second film, “Unconditional,” is personal. It follows half a dozen family caregivers as they navigate emotional and bureaucratic minefields. The film follows a diverse array of caregivers from all different backgrounds, across the United States. It also follows Lui himself, after his father received an Alzheimer’s diagnosis in 2014. Lui’s father passed in 2021. He and his siblings are now caring for their mother.

Lui was the first Asian-American man to anchor a cable news show in the United States, although not the first Asian-American person to do so – that honor goes to Connie Chung. In 2013, Lui won the Asian American Journalists Association’s Member of the Year Award.

The 19th spoke with Lui about his journey as a family caregiver, telling the stories he wants to see and the process of making a film he described as, “finding a way to live and embrace both the bad and the good.”

“Unconditional” will play at select theaters May 3-9, as well as stream on PBS.org through July.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sara Luterman: Tell me a little bit about your caregiving journey. How did caregiving become a part of your life?

Richard Lui: I didn’t know that I was a caregiver when I started, when my dad was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

The big indication was when his youngest sister — and he comes from a brood of 13 kids, he was number eight — when his youngest sibling came over to me at our Christmas dinner, and said, “Hey, your dad just forgot my name.”

And then I knew it hit a point. There’s layers to what you start to forget first. And the layer that he started to lose, which was very surprising, was his siblings, because they were super close.

So that’s the point where I reached out to my boss [at MSNBC/NBC] to see if I could work in a different way. I knew that the answer was probably going to be, “No.” The answer was probably going to be, “You’re a great guy. We like you, Richard. But when you’re done with this journey caring for your father, then call us.”

That was the beginning of being a caregiver. That moment I made the decision. But I didn’t know I was a caregiver. I didn’t self identify with that term until I did a video with AARP on Asian Americans and caregiving.

When they first asked me about the video, I asked, “Why would you do this?” And then they said, “There’s a lot of you folks out there doing this, you know.” I didn’t know at the time that there were 48 million caregivers out there — 2.7 million Asian-American caregivers. I think it’s probably gotten higher in the past three years [because of the pandemic]. So that’s when I started thinking of myself as a caregiver.

AAPI Heritage Month: Our legacies, our experiences, our future

This story is part of our AAPI Heritage Month coverage. From recommended reading to staff reflections and historical data, we’re focused on telling stories highlighting the past, present and future. Explore our work.

It took you a while to identify as a caregiver. Do you think there’s a gender angle to that? Many people don’t think of men as caregivers, necessarily.

My father was a pastor, but he was also the kind of person who would do things that weren’t necessarily, stereotypically associated with being a man. He’d express his weaknesses. He would talk to me about the difficulties of working through a 50-year marriage. He would cry in front of me. But he would also laugh with me, he would also fight for me. I would say that the way he expressed himself did not fit the stereotypes of gender. And when you add on the layer and the intersection of race on top of that, both of those together, those two intersectionalities — he honestly lived by his heart. And that was what shaped my sense of myself as a man.

I think that’s part of why I’m here talking about [caregiving]. Seven, eight years ago, I never thought I’d be talking about my mental health or my emotions. About 25 percent of family caregivers are men, but we’re less likely to talk about it. That’s not helping to offset the stereotype that caregivers can only be women, or that they need to be women. That’s not true, and it’s unfair to women.

My mom, because of the time she grew up, she had to become a schoolteacher. I respect it fantastically. But I believe her heart was in being an artist. She was the youngest daughter, the one who cooked, the one who did the books and closed down the corner store for the family. And later, when my dad got sick, she stepped up to that too. She always had a brave face.

When I started staying overnight, caring for my dad, I realized what a big job it was. She had been sleeping on the couch, because my father would get up at all hours of the night and try to wander out the front door. She never slept in the bed again until he passed, even when I was there. That was the level she gave of herself.

Was it frightening to ask your employer if you could work fewer hours? I know a lot of employers would probably let someone go for that. Or pressure them to quit.

It’s crazy. Especially in our business. I walked in the room knowing I needed to take care of my dad, because I wasn’t not going to do it. He would have done the same for me.

It’s still very vivid in my mind. I walked in. My boss, Yvette Miley, is a consummate journalist and an amazing editor.

I remember her looking over at me. She had her glasses on. And I said, “I think I need to be back home. And I don’t know what that means for what I’m doing here.”

At the time I was working a lot. Maybe seven days a week. She could call me any time. And I would fly out to stories: Michael Brown, the Paris Bataclan shooting. If I was going home and wasn’t available to work, that meant I was no longer going to fit that role.

Yvette looked over at me and pulled her glasses down her nose.

She said, “I’m a long-distance caregiver too. I shouldn’t say I’m a long-distance caregiver. I also take care of my mom. She’s in Florida.”

So my first thought was that it was the first time she’d ever told me about her family.

My second thought was the realization that she was going through what I was going through. She was doing the same thing I was doing. I couldn’t believe it.

So she pulled out her reporter’s notebook and said, “Let’s come up with a list of ideas together, Richard, for how we can keep you on. Let’s both think and meet again in a week.”

And that’s how it began. She helped me keep my career.

What kinds of tasks were you doing to help care for your father? How did you share those responsibilities with your siblings?

I was flying from New York to California two or three times a month. And we, three of the four of us siblings, would help out to split the duties. But in the beginning, it was mostly me that would stay overnight — two or three nights in the beginning.

The tough part was that we didn’t have all siblings on deck. We still don’t, even today, caregiving for our mother. We’ve always had a majority helping, though.

You have a documentary coming out called “Unconditional.” Can you tell me a little bit about it?

It took me two years to edit. It was almost like a therapy session we had every week. I would sit with the editor and the other producer, and we’d be making editorial decisions down to the second. I would have to describe the dynamics of caregiving out loud for the first time. One of the biggest things for me was making sure to include joy and not just difficulty. I put it in our treatment, I put it in our press kit, I put it everywhere, because I didn’t want us to think that caregiving was only reductive. Caregiving is a one plus one equals three. You don’t know it during it sometimes. But it’s happening.

I’m not a person that uses the word “love” a lot. I believe in it. I practice it. I see it. It makes me cry, makes me laugh. I don’t shy away from it. I just don’t say it. I do it instead.

But this film got me to say things I’d never said before about caregiving and the complexities of it. During the last two or three years, when I had to say what mental health meant in this journey for me, for the documentary, I’d say, “I don’t know if I’m OK.” But it’s OK if I’m not OK. It’s important that I admit it.

Caregiving isn’t negative all together. And it’s not positive all together. It’s 50/50. An earlier title for “Unconditional” was “Hidden Wounds.” I thought it was a good working title, because there are hidden wounds on the caregiver side and on the recipient side. But it was missing something.

Do I want people to think about wounds? Just be really simplistic about it? No, I don’t, because that’s not the truth.

You’re flying home now to care for your mother. Her arc is also a big part of “Unconditional,” going from a caregiver to someone who needs care herself. How is she doing?

My mom was officially diagnosed with Alzheimer’s a few months ago. She’s coming up on 90 and she’s a brave woman. She has low blood pressure and sometimes it will cause her to be unable to function. Which is complicated, because she’ll still try to walk. It’s difficult. But also empowering. She’s still trying.

Is there anything I didn’t ask about that you think is important for people to know?

The one great thing about caregiving is that it highlights the empathetic parts of ourselves. We all have differences, based on our backgrounds. Socio-economic, regional, race, gender, all of these things. But at the end of the day, what I love about talking about caregiving, is that it erases all of those differences in ways nothing else that I’ve reported on has. It’s something that impacts everyone.