This AAPI Heritage Month, we’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

Connie Wang is a legend in the world of digital media. As the former executive editor of fashion and culture site Refinery29 and the host and co-producer of the Refinery29 documentary series “Style Out There,” Wang not only helped shape an entire generation of Internet content, but has for decades now been a foremost voice in fashion and culture reporting.

But if you ask Wang, the real legend and ur-influencer is her mother, Qing Li.

“Anytime I would write an essay about my mother, those would be the pieces that people would always bring up to me, that people would email me about,” Wang told The 19th. With her penchant for middle of the night cleaning sprees, love of extreme fashion choices, propensity for serving ice cream Drumsticks for breakfast, and obsessive love of all things Magic Mike, Qing’s presence has always loomed large, at home in suburban Minnesota, or wherever the Wang family’s life travels have taken them, despite some unexpected twists and turns.

Qing Li thought she was coming on an extended vacation in America when she arrived in 1989 to visit her husband, Dexin Wang, who was completing his doctorate in nanomagnetics at the University of Nebraska. The fashion-loving Li planned to eventually return to her job as an editor of nonfiction books with a prestigious Chinese press and be back with her young daughter, Connie, who she left in the care of relatives.

Then, the Tiananmen Square protests happened back in Beijing. Dexin Wang was photographed showing his support for the demonstrators. After the protests ended in dispersal and death, it quickly became clear the couple could not return to China. They sent for 2-year-old Connie, and just like that, the Wang family found themselves as new immigrants in America.

AAPI Heritage Month: Our legacies, our experiences, our future

This story is part of our AAPI Heritage Month coverage. From recommended reading to staff reflections and historical data, we’re focused on telling stories highlighting the past, present and future. Explore our work.

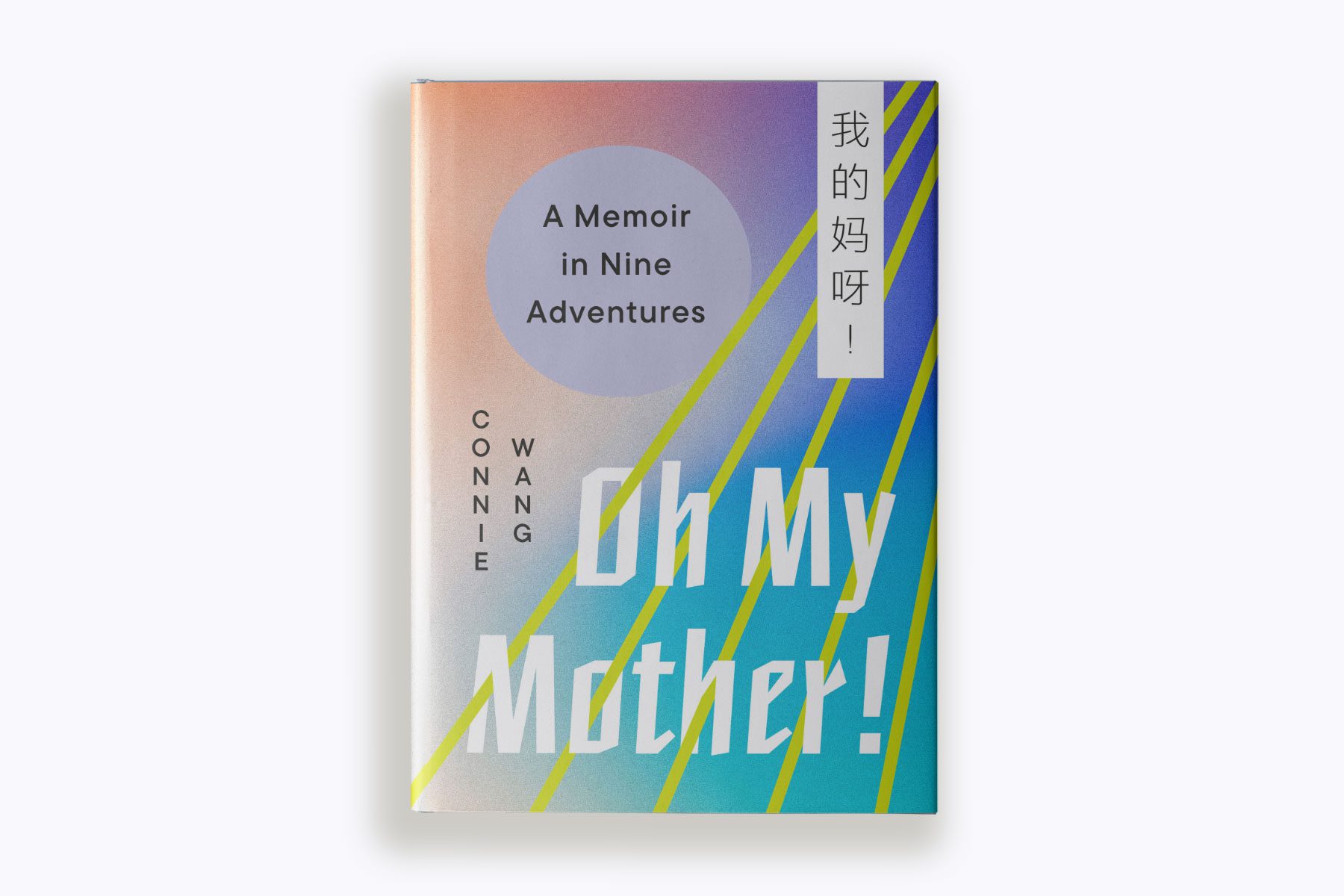

In her debut book “Oh My Mother!,” Connie Wang writes a kind of memoir of her relationship with her mother through a collection of essays about seminal moments in their lives when their travels took them outside of their comfort zone.

Wang spoke with The 19th about her new book and how writing it helped her understand her mother in relation to her own immigration experience and the concept of Asian-American identity.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What did you realize about your mother that you didn’t know before sitting down to write this book, and what did going through this process of trying to understand her tell you about yourself and the identities you carry?

I had always assumed that my mother was intentional in the way she set out living her life — that every single sort of chapter and phase of her life was mapped out and that she had meant for it to happen and then it happened. I think this was because growing up, things were very strict. There was always this pervasive sort of fear of disaster looming around the corner, and if you weren’t prepared, if you didn’t know what was around that corner, if you didn’t do your homework and know what was coming, the surprises would happen. And you absolutely don’t want that.

I always thought that my parents have always been this way and I never realized that they were only this way because of the gigantic sort of shifts and pivots in their lives, and what happened because they just weren’t prepared and they didn’t know. Even the fact that we were in America was somewhat of an accident, and then there were all of these huge consequences of what came next — how it affected my mom’s career and her sense of security, her ability to have access to friends who spoke the same language as her and had the same interests as her.

In writing this book, I realized that parents are just adults and, especially when it comes to parents of the previous generation, really young adults. They don’t so much make decisions as they just survive their lives.

In writing about your mom, how did you come to understand how her identity was shaped by her immigration experience?

When my parents came to the United States, the idea of being a minority was a completely foreign concept. Their community at the time [in China] was so very homogenous — it was politically mandated to be homogenous. There had been decades spent of people really trying to just clip off the edges, to make sure that there were no classes, no differences between groups, that everyone lived the same way.

When they came to America, thinking about being Asian in America and what it would mean to be Asian American was not something that they really thought about. It was more just, “How the hell are we going to do this?” They were focused on what skills transferred and how they were going to be able to make money and find careers, and then, secondarily, maybe find a community.

How did this help you think about what it means to be Asian in America, and what the term “Asian American” even means in navigating American life today?

In the book, I talk about how my family always went on these road trips, and on these, we have traveled to Chinatowns throughout America. We went to San Francisco and New York and other major Chinatowns throughout the country, and as a kid, I was always so confused by the fact that my parents weren’t more excited about this. I couldn’t understand why visiting these Chinatowns didn’t feel like a homecoming to them, and why they always seemed to feel very distant to them and a little dismissive of them. I was always like, “Aren’t you so excited to eat chop suey?” And they would be like, “No this is not our generation, this is not even the region of China that we come from.”

This may be dirty laundry among Asian Americans, and Asians in Asia too, but Asian Americans don’t see themselves as some sort of collective group.

“Asian American” is such a strange phrase. There’s a lot of resentment and anger and historical feelings between countries and people’s own histories in their home countries and outside of it too. And then all of that gets transported when you immigrate.

So when my family first immigrated, there were Koreans and Japanese people in our community, and they’re like, “Well, those aren’t our friends.” My parents didn’t speak English, and they weren’t going to be friends with the other people who also didn’t speak English, and who they also didn’t share a language with. They were not more inclined to be friends with people who were “Asian American” who weren’t Chinese than they were to be friends with White Americans or anyone else.

But anyone who had a face like ours would end up clumped together. So you would try to seek out opportunities within that and be like, “OK, so I know we are all ‘Asian American,’ and what are the stereotypes that work in our favor?” It was about using the tools you had in order to keep going.

In taking this time through this book to think about your mom and her life — and what you have learned from her — what do you think is the biggest lesson you realized she taught you?

I know this sounds so highfalutin, but self-actualization is so important — the ability to be able to dream about a thing in the distance and then knowing you can get there if you try. Luck can affect it, the resources that you have to support you come into play, knowing that something coming out of left field isn’t going to take you down — but being able to have a dream in the first place is so important.

My entire career as a writer, whether I was applying my words to fashion or culture or politics, I found that the lack of actualization is just the most crushing thing a person can experience, whether it’s through formal public policy or through familial or social pressures. I have always looked at the intersections where people weren’t able to actualize and the ways in which they then pushed back against those forces, and I have tried to celebrate these people because it’s a really brave thing to do, to push back. And sometimes, the way people push back takes really beautiful forms. I think the most beautiful, creative art is made in these moments. But I think if you ask any of these people in any of these communities who are experiencing oppression at any sort of level, would they rather not have to do that? They would be like, “Yeah, for sure.”

I think we forget how often people are making the best out of shifts or situations that they can’t control.

As a new mom, how do you feel the way you feel that idea of self-actualization now translated into your own life?

As a mom, there’s so much that happens outside of your control. I see my son already is so clearly his own person with his own ideas and his own dreams and his own path. I want him to be able to get to where he is going. The idea of him not being able to get there because of something that’s outside of his control is terrifying to me. I feel that in my bones and I know that’s because of how my mom also sees my life.

As a new parent myself and having a very good relationship with my own mother and understanding how she sees her own life, she has such an incredibly optimistic perspective on her own life. I think that is really unique, especially for women in her circumstances and at her age.

It’s been possible because she’s been very lucky to find herself in a country that allows her to do that. She found herself in a city in Minnesota that allowed her to do that. She knows that she has the right to vote and believes she can vote her way out of certain circumstances.

Learning about my own mother has taught me that we can help each other self-actualize. I saw how it was possible for her.