Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month is a time to celebrate the contributions made by the generations before us, and to honor those whose struggles paved the way. Growing up here in the United States, most AAPI had relatively little access to the history that shaped our parents, and in school we learned virtually nothing about people who looked like us. We’re still learning our own stories even as we carve out our own path.

As we grow more visible, we are claiming our place economically, socially, statistically, politically. We do not do this alone. We lean on not just our families but also the storytellers and community leaders among us who give us the strength and inspiration to keep going.

Several AAPI staffers at The 19th have come together to reflect on that strength and inspiration. We look to our families, to educators, to journalists and advocates who pulled threads from the old world and wove the familiar into something new.

‘Why didn’t I know about it?’

I always struggled to learn more about South Asian history, and the history of Pakistan in particular. Many history books available in English are written by White men. Other books demonize one side or the other. It wasn’t until college that I learned about Partition and how it divides some immigrant communities. It’s been a deep source of shame for me that I do not know more about my culture’s history, and in the worst moments I feel unmoored, too unlike any part of my heritage to cobble together a cohesive identity.

My cousin Neha Aziz changed that. In 2022 she created a podcast called “Partition,” 75 years after the division of India and Pakistan, to tell this important history. She made an incredible series by interviewing artists, survivors and academics, paying particular attention to the experiences of women, creating a resource for people like me. It is also special to listen to her interviews with our shared family members.

Neha, a journalist and filmmaker, had never heard of Partition until visiting Pakistan and was motivated to learn more about this trauma that has reverberated across countries for generations. She unapologetically called attention to this history and asked, “Why didn’t I know about it?” Her sharing her own experience affirmed my own. I’m proud of her, and her work inspires me to write stories focused on communities who are often left out of the narrative. – Jasmine Mithani, data visuals reporter

AAPI Heritage Month: Our legacies, our experiences, our future

This story is part of our AAPI Heritage Month coverage. From recommended reading to in-depth Q&As and historical data, we’re focused on telling stories highlighting the past, present and future. Explore our work.

A way forward for Cantonese

Language anxiety is something that all migrants grapple with and that diasporic children can’t often articulate — like your breath catching when you just want to say thank you, because what if you pronounce it wrong? If I can’t communicate properly, am I really enough? As a heritage speaker of Cantonese whose family moved from Hong Kong to North Carolina, my own language anxiety comes in waves and has gained an additional layer of urgency as Hong Kong moves onto a path not entirely of its own volition.

Cantonese is in danger of being lost as a language, and with that comes the loss of creativity, communication and community. Which is why I’m so thankful for people, often through social media, working to preserve, expand and teach Cantonese. With new children’s books and textbooks being published, colorful Cantonese slang being explained alongside classic movie clips, and pressure to create and maintain Cantonese language courses in universities, there are more access points now. Two projects in particular embody what that could look like: Cantonese Connection, a community built by artist Pearl Low that not only provides resources, but a compassionate framework for learning Cantonese as a diasporic person. And BLM Cantonese, a project “to confront racism in our communities by removing language barriers in social justice conversations.” They, and others, can lead the way forward in our globalized society. – Wynton Wong, multimedia events producer

Embracing American fashion and absurdity

My mom’s mom, my popo, loved purses. They were all she wanted to look at, her reason for shopping. Her keen eye and sharp memory meant that she could tell whenever anyone added a new player to their lineup.

“Is that a new purse?” she’d interrogate in Cantonese. “How much?” she would ask, kicking off our own version of “Price Is Right.”

“Guess!” I’d demand, and the game would end in either trills of delight at a good deal or tuts of disapproval for overpaying.

To my popo, who arrived when she was 55, purses weren’t just a fashion accessory, but something to browse and covet while wandering the giant malls of America.

My popo found a lot of American culture to be hilarious. (Why did Mister Rogers take his shoes off at home just to put on another pair?) And when things didn’t make sense to her, she’d just sit back and cackle. Watching TV with her taught me to consider how absurd life could be and how to laugh at it.

However, I always got the sense that she might’ve been lonely here. My popo lived a pretty full life back in Peng Chau, an island off the coast of Hong Kong. She was able to create some social circles in San Francisco, but nowhere near the same scale. And she never really took to English.

But she gave it her best. The fullness to which my grandma laughed, lived her life, bought her purses and made the most out of what she had is what sticks with me still and gives me strength. – Julia B. Chan, editor in chief

5 feet, 9 inches of tenacity

My father’s mother — my nainai — lived a long, tough life, outrunning the Japanese, the Communists and even COVID-19, briefly. Nainai was 5 feet, 9 inches of tenacity. She pursued her studies through years of air raids. (“You just evacuate with the school.”) She braved checkpoints alone to find her father in the middle of a war. (“Carry breakable gold jewelry for bribes.”) She was fierce and frugal, constantly micromanaging her sons but also saving every penny to pass on to their families. As her favorite grandchild, I received only the upside of Nainai’s love. She lived far away, but visited often enough to know all my childhood friends. A career teacher, she read my painstakingly written Chinese letters, and sent back edits with her replies. She was strong not just in body and spirit, but in her genes: Her face, my father’s, mine and my daughter’s might as well all be mirrors of one another. Nainai’s strength gave my family what we needed to flourish here. It’s my job to pass that on to my children. – Flora Peir, news editor

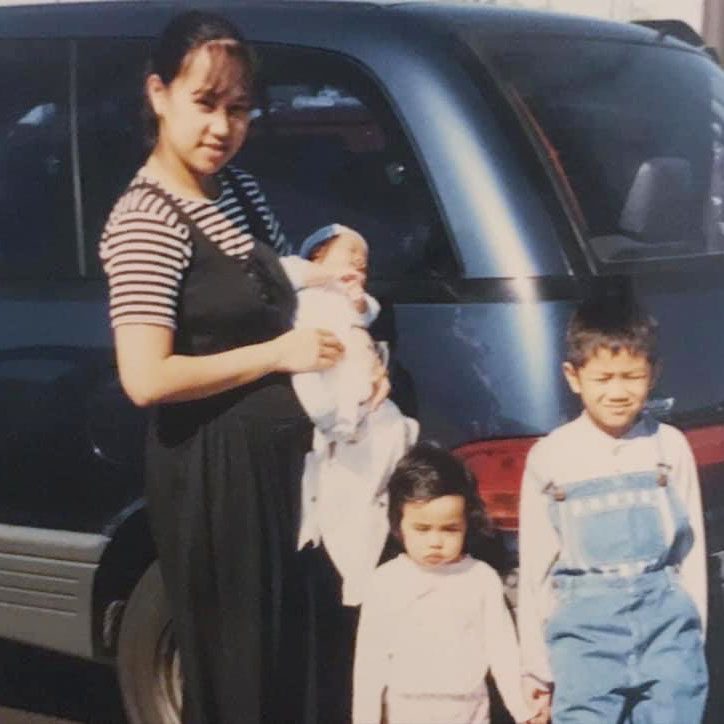

Where our resilience took root

We affectionately refer to it as “The Blue Whale,” a blimp-shaped, clunky minivan that somehow still passes as street legal. But the 1991 Toyota Previa DX — a model discontinued in 1997 — was sleeker and brighter in its youth. My parents, Filipino immigrants who met at graduate school in Ohio, bought it used in the early ‘90s.

The van became an important member of the family, a reliable transport and safe haven on our countless road trips. I joke that I grew up on the road with memories of my nomadic parents shaking me awake to climb into the makeshift bed in the back, sandwiched between my two brothers. I watched the stars through the back window; I saw my first mountain and waterfall from the passenger seat; I developed a wild animal phobia after monkeys pulled the wipers off at a drive-thru safari. Our family laughed, fought and learned in that 15-by-6 foot box on wheels — and whatever was created in that space continues to give me strength.

Last year, my parents sold my childhood home and carted decades of memories into dumpsters, but when they tried to send The Blue Whale to wherever vehicles go to die, my younger brother — expecting his own first child soon — stepped in to adopt it. – Mariel Padilla, general assignment reporter