We’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

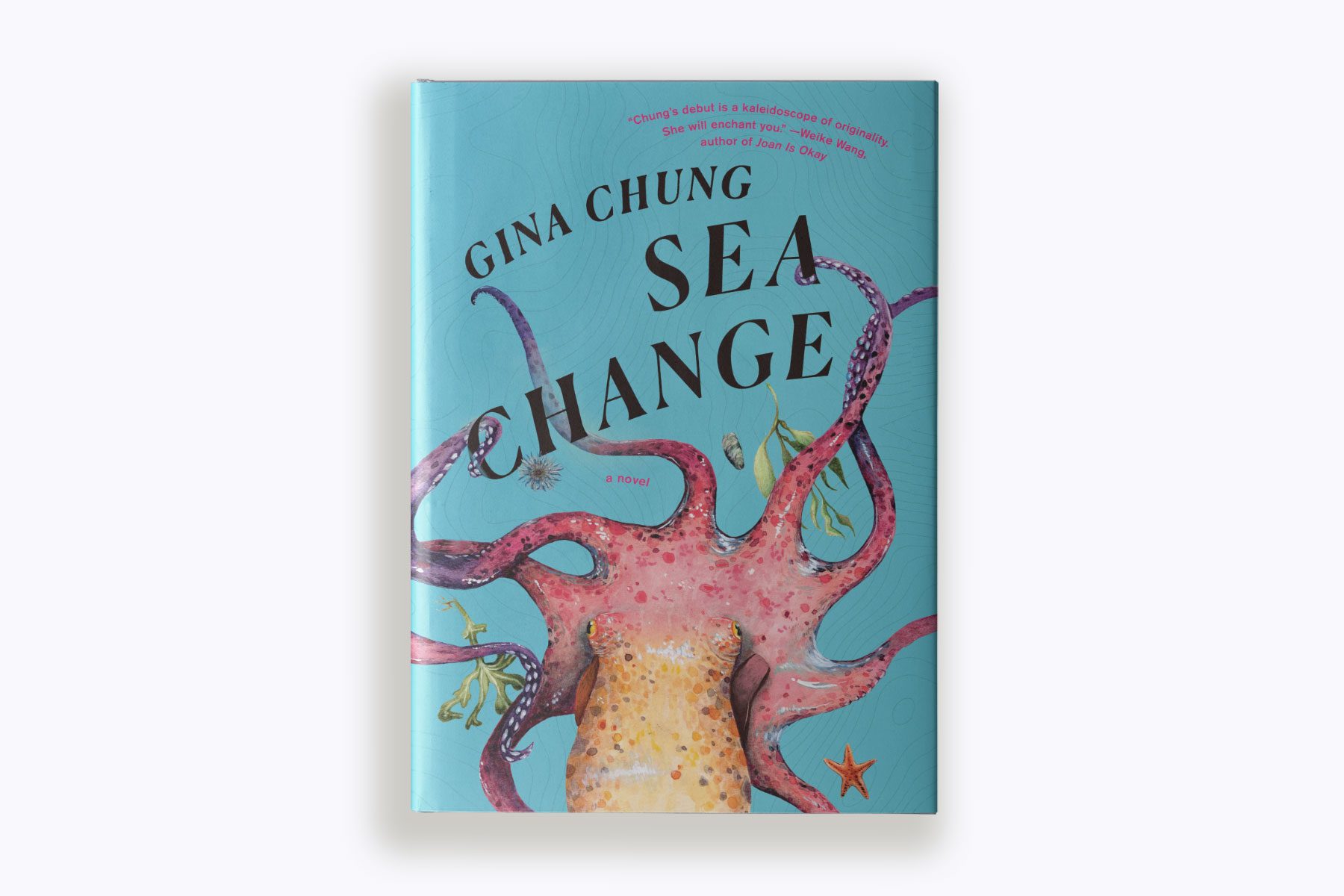

Ro is having a hard time. The protagonist of Gina Chung’s debut novel “Sea Change” has recently turned 30, and nothing in her life feels on track. She’s been working at a mall aquarium in New Jersey since she graduated from college and sees no path forward for her career — and now the failing aquarium is thinking about selling the creature she considers to be her best friend, a giant octopus named Dolores who was discovered by her father shortly before he disappeared on a subsequent research trip.

When it comes to her human relationships, she’s not faring much better. While Ro stalls, her childhood best friend Yoonhee is racking up wins in and out of the office and leaving Ro behind as she does. Ro is more or less estranged from her mom, who suddenly very much wants to see Ro after another routine, prolonged period of not being in regular communication. And Ro’s boyfriend Tae has broken up with her to join a privately-funded mission to colonize Mars as climate change ravages the planet (and after Ro told him she wasn’t ready to move in with him). Dirty dishes and empty beer bottles are piling up in her sink, and her only non-work plans are either drinking Sharktinis (Mountain Dew, gin, and jalapenos) from her couch or drinking by herself at night at her local bar and daring herself to see if she can safely drive home. It’s safe to say that things could be going better.

In her enveloping and imaginative speculative novel, Chung has created a richly detailed and beautifully emotive portrait of what it means to be lost in your early 30s when you’re not sure if you want to be found. At the same time, the novel serves as a nuanced portrait of what it means to be a Korean-American daughter of immigrants reckoning with the legacy of immigrant trauma and to live within — and beyond — the expectations put on you as a result of your gender, race and ethnicity.

Chung spoke with The 19th about what it means to write at the intersections of identity while exploring what it means to be yourself in a world where the bottom keeps collapsing.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jennifer Gerson: In your novel you have this woman protagonist who is messy. She’s also the child of immigrant parents and is Korean-American and grew up in New Jersey. What did it mean to you to write this kind of character and think about taking on so many aspects of identity through writing fiction?

Gina Chung: In writing Ro, I really wanted to write a character who was Asian American — who was Korean American — and who was like a version of people I’ve known all my life, but I feel that I don’t get to see depictions of in popular media. I think there has been a push lately towards way more depictions of messy women, women who are experiencing really uncomfortable and not “feminine” types of experiences and feelings, but I think a lot of those depictions are still largely created by and mostly for White women.

With this character, you also see the legacy of immigrant parent trauma and how you’re also not really able to express the full extent of the emotions that that brings up because there’s often this sense in immigrant families of inter-family solidarity through keeping silent about the things that are not so pretty and that are uncomfortable for everyone to talk about. [With immigrant parents], there can be a pervasive sense of, “We have gone through all of these things so that you, in turn, can supersede us and go beyond all of our expectations,” which is an immense pressure for anyone to have to live up to.

In writing this novel, how did you think about the pressures women feel to appear to be different things to different people — especially when they feel so messy and unsettled inside, to themselves?

I think [Ro’s] experience of being someone who doesn’t really have it all together and is really not that good at taking care of herself or always making the right decisions is something that so many of us as girls and women really relate to, especially as we are coming of age, especially when we don’t really know who we are yet.

Ro has so committed to the bit of doing her fun escapist thing, where she goes to her local bar and drinks until she almost passes out, that she doesn’t realize yet that it’s not actually any fun for her. I think that’s an experience that so many women have, where you’re just taught that you have to be ready to have a good time at all times and that you also have to be ready to be the recipient of this kind of not-necessarily-wanted male attention and to think that if you don’t get it, you’re somehow worse off. If you don’t get it, you might as well be nonexistent.

This is a novel written through a very specific cultural lens. When you look at the current literary landscape, how did you feel in writing a story that is so palpably about being proud of your identity and heritage?

There’s this thing that I think happens to immigrant kids, where [you want] to write about the world you come from, but feel that maybe you don’t quite have the authority to write about that world or the ability to really access it. That was something that really held me back a lot in my early years of writing.

It was really important to me in writing this story as someone who is Korean American. When I was growing up and reading — which I was always doing — a lot of the books and stories that I first encountered were about White kids. This just became more and more true as I got older and read a lot of classic literature. So I grew up mostly thinking and reading about White characters. Then when I started writing my own stories, all of my characters were White. It was just a reflection of what I was thinking about and reading.

It wasn’t until I got older and was able to access Asian-American writers and writers of color — and after not necessarily being taught about these writers in school, but just coming across them on my own at the local library or the bookstore — that I realized, “Oh wait there’s a whole other way to write about us.”

This novel really digs into the question of what it means to be a daughter in terms of the assumed binary of “not-a-son.” How did you think about gender in trying to understand the definition of “daughter” in writing this novel?

Most of the time when we think about the role of daughter, whether in fiction or in film or TV, it’s usually through the lens of mother-daughter relationships, but there’s also so much to unpack with the specific gender roles that exist within a family and how you might relate to your own father as a woman coming of age.

There’s a way in which women and girls, from a very young age, are expected to fulfill a lot of not just the domestic tasks, but also the care work that sons and boys are not often expected to do. I don’t have brothers, but when I was growing up, my mom always used to say to me that in traditional Korean culture, sons are very valued — but daughters are the ones that bring families together. I always thought this was fascinating, because it was clearly meant to be a very positive thing that daughters get to do. But I also always thought that was such a burden.

The fact that that expectation does not exist for men and boys is really fascinating to me, the idea that boys will grow up, get married, and start their own families and then that’s kind of the end of it — but that for girls, no matter where they go in life, are expected to always be tied to their parental roots.

The novel is also a very nuanced portrait of female friendship and the significance these relationships play for women and how they figure out and move through the world. What felt most important to you to call attention to in writing how imperfect but important these relationships are?

Growing up, I always looked to other girls and other women who were my age or even just a little bit older as models for how to live my life. Girlhood is such a fraught thing and to be going through that with friends is such a gift. I have friends who have known me since I was like 10 years old or younger, and as you get older and your lives maybe diverge you may not necessarily be as close as you once were, but whenever I get together with those friends it’s such a gift to know that they have access to those past versions of me and that I can do that with them as well.

I think we live in a world in which romantic relationships are still very much prioritized over platonic relationships and friendships, but for me — I don’t know where I would be without my female friendships, and I really wanted to explore that in the novel.

This is also a novel about grief and what it means to incorporate loss into your identity, day to day. How did you think about gender and what it means for a person to figure out who they are, relative to their grief?

I think a lot of the time, women are expected to be the containers of feeling in our communities, holding all of the losses and grief. This isn’t to say that men don’t experience these feelings too, but there’s always a sense that women are still seen as the emotional caretakers of all of our feelings.

I read once in an article that whenever there is ambient shame in a room, it usually lands on the women in the situation. I feel that way about grief too — whenever there is sadness or loss, there’s this sense that if you are the daughter or you are the mother, you have to be the one to carry it with you always.

This is also a novel about climate change — why did taking on that idea feel like an important part of telling this character’s story about understanding her own self?

I was inspired in part by the idea of the floating plastic islands out on the Pacific Ocean and also I was inspired by a short story by Karen Russell called “The Gondoliers,” which is sort of a post-apocalyptic narrative about Florida and the aftermath of rising sea levels. In that particular story, it’s about how sisters act and create this one kind of family structure in what we would call a wasteland. I was really captivated by the idea of how you could take something like a climate disaster and make it into something that isn’t necessarily like an ending.

I wanted to think about what the end of the world would look like, but instead of through a lens of, “How are people going to live in the midst of this?” I mean, we are kind of all living in the midst of it right now. But how would that change our relationships to each other and to our environment?

That’s what brought on the idea of Ro having gone through this breakup and the breakup itself being extraordinary in that the man who is the love of her life is not just leaving her, but he’s leaving the entire planet. Living in these times, I think a lot about our human responses to how complicated this all is.

How do you think about how genre works in telling the kinds of story you wanted to tell here and the way you got to explore these questions about identity and self?

I personally just really love when fiction can put us into a world that is ever so slightly off-kilter from ours, where the day-to-day fabric of life might look similar, but the technology is slightly heightened to make it so that we don’t have to think about making certain choices. For example, the dating app I write about in the book — I really don’t think we are that far off from something that analyzes all of your private bio data in the name of granting you your “perfect match.”

I do think we are already living in a speculative world where almost every day, you’re hearing about these new technological innovations that would have been unthinkable five, 10, or 20 years ago. But at the same time, there are obviously still so many issues that those innovations don’t really address in people’s day-to-day lives, like how to heal from a broken heart or how to get over a misunderstanding with your closest friend. I think that those are the issues that are always going to stay with us.

Chung’s recommended reading

For more novels about complicated, messy women as they navigate the many facets of their identity, here are a few that Chung recommends.

“Severance” by Ling Ma

It’s a millennial coming-of-age story about work and what work means in the face of late-stage capitalism, but it’s also a zombie novel. I found it to be such a poignant, layered and textured way of looking at the complications of being a woman and of being Asian American and being an immigrant and trying to make your way through all these various situations of dealing with identity while also dealing with the extremely extraordinary circumstances of that book, which are that zombies are taking over the world.

“Chemistry” by Weike Wang

This is a seminal text for me, even though it doesn’t have post-apocalyptic vibes. It’s a story about a young woman who’s a chemistry Ph.D. student and she ends up having to drop out of her program because of the attendant pressures of being in a really difficult field and of being a woman in the sciences. She’s also struggling to live up to the immense expectations that her immigrant parents have put on her, and I realize this all sounds very serious, but it’s such a funny and poignant read. It was one of the first books I read that made me want to be a writer.

“Pizza Girl” by Jean Kyoung Frazier

This is another book I think of as being a critical part of this new loose subgenre of books about the complications of growing up and being a woman and being uncertain as to what you want. The main character is around 18 or 19, and she’s pregnant, and she’s working at a local pizzeria and in a state of frozen staticness about her life. It’s a very funny kind of millennial slacker story. She unexpectedly comes face to face with a woman who ends up changing the course of her life. It’s also an examination of father-daughter relationships because she’s also dealing with the legacy of a father who is no longer in her life.