After eight years of politics reshaped by President Donald Trump, Democrats went from being in disarray to putting forth a united front and big tent opposing him. And they lost anyway.

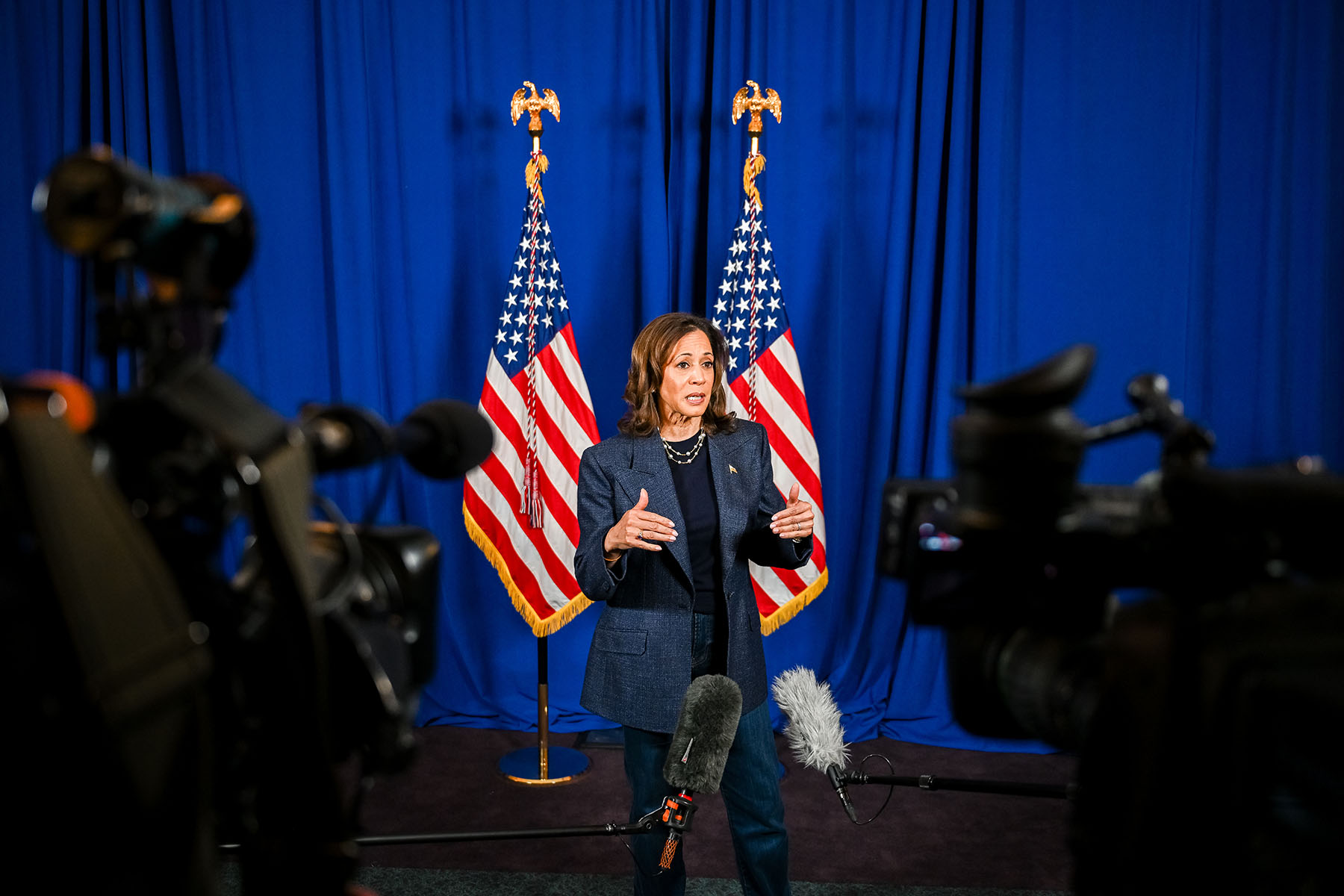

Vice President Kamala Harris’ loss after an unusual and truncated campaign marks the second time the American electorate has selected Trump over a Democratic woman. This time, returns indicate a broad repudiation from voters not only of Harris’ candidacy but also the Democratic Party’s policy agenda, messaging and broader vision for the country.

In defeat, 2016 Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton still won the popular vote, giving Democrats hope that Trump’s victory was an aberration that wasn’t representative of the people’s will. Those hopes were bolstered by big gains in the 2018 midterms. Eight years later, in 2024, Trump is poised to sweep all the major battleground states and become the first Republican candidate to win the popular vote in 20 years. Exit polls and county-level results show a sizable shift to the right, one that appears to be driven in large part by younger voters and Latinx voters.

After 2016, shaken and demoralized Democrats endlessly dissected the reasons behind Clinton’s loss — and prized the elusive and often gendered notion of electability above all else. The party’s choices since — from nominating President Joe Biden for president in 2020 to pushing him to step aside after his disastrous June debate performance against Trump — came from the desire to beat Trump at all costs.

While polls showed a tight race, Harris’ loss in a high-turnout, high-enthusiasm environment shows how the party’s messaging fell flat across the board. It wasn’t that Democrats stayed home, but rather that many, especially in blue states, voted for Trump — and embraced his campaign vision, which appealed to voters for different reasons. He offered a mix of promises to improve people’s lives and punish America’s enemies through an aggressive vision of masculinity.

In 2016, the American electorate was taking a chance on Trump, an outsider who rode the wave of emerging economic populism and capitalized on Clinton’s unpopularity and a lower-enthusiasm environment. But in 2024, voters have decisively welcomed back a former president who, since his first election eight years ago, has been impeached twice, including for inciting the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the Capitol; was convicted by a jury on 34 felony counts; and has been found liable of sexual abuse, fraud and defamation.

Experts say that persistent gender biases against women candidates played a role in both Clinton’s and Harris’ losses.

“Kamala Harris’ candidacy exemplified a good deal of what our research tells us about women’s advantages as candidates and officeholders. She was a formidable fundraiser. She connected with voters on issues important to her and to them. Her identity provided her with unique perspectives on overlooked issues,” according to a statement by the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, released on Wednesday.

“Unfortunately, this contest also exemplified research on the obstacles women face when running for office, chief among them the unequal expectations placed upon women, and women of color in particular, who run for office,” the statement added.

Clinton came into the 2016 campaign with a national profile and a wealth of experience as a U.S. senator and secretary of state. But she was weighed down by an FBI investigation into her use of a private email server that reopened just days before the election. The probe — and a damaging and embarrassing hack of her campaign over the summer — added to the baggage that came with her decades in the political spotlight. Those factors, aided by bias against women candidates, contributed to her negative favorability ratings. A degree of hubris and unwarranted confidence within the campaign led to a series of well-documented strategic missteps.

The 2016 general election came after a bitter and bruising primary fight between Clinton and Sen. Bernie Sanders that left the party deeply fractured. Democrats pointed to third-party candidates and the “Bernie or bust” voters who stayed home as factors contributing to Clinton’s Electoral College loss.

Turnout in 2016 was also relatively low, giving Democrats room to both repair and expand their coalition. The popular resistance to Trump’s first term gave them a roadmap to gain ground in special elections and the 2018 midterms, which became a blue wave. And Democrats, including Biden, catered to the progressive wing of the party with appointments and an ambitious legislative agenda, including several major economic spending bills.

In 2024, the Democratic establishment coalesced in support of Harris within hours of Biden’s dropping out — but the party unity didn’t carry the day. For all the attention devoted to third-party candidacies like Jill Stein and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., their impact on the race appears to be marginal.

In her 107-day presidential run, Harris ran a fast-tracked but highly disciplined campaign with few mistakes or gaffes and fueled by a groundswell of grassroots support and enthusiasm that was lacking from Biden’s reelection effort. She barnstormed battleground states and poured money into ads on highly popular and galvanizing issues like abortion.

Harris, unlike Clinton, also did not emphasize her gender and the history-making nature of her candidacy. Positioning herself as a new generation of leadership, she pivoted to the center and made a concerted effort to reach across the aisle to disaffected Republicans in key swing states.

Harris was also more popular than Clinton and even improved her favorability ratings over the course of her short campaign — a remarkable feat for a national candidate in a highly polarized national environment, making the scale of Harris’ defeat that much more striking.

After she became the nominee, Harris gained on Trump in polls on the defining election issue of the economy and inflation.

An October survey from KFF, a nonprofit health policy research, polling and news organization, found that a greater share of women voters said they trusted Harris more than Trump when it came to the economy, which they also named as their top concern. When the survey was conducted in June, Biden was still the Democratic nominee and women voters were evenly split on which party they believed could better help them manage rising costs.

The KFF survey also appeared to validate the logic behind the nominee switch. It found that since Harris became the nominee, 64 percent of women voters say they were satisfied with their choice of presidential candidates for the 2024 race. Only 40 percent said the same in June, when Biden was still the Democratic nominee.

The results so far show Harris put up the strongest showing against Trump in the battleground states where she and her allies invested the most time, travel and ad spending. But the results in safe blue states show the extent of the collapse in Democrats’ support.

“It was closest in the places we competed,” Harris campaign chair Jen O’Malley Dillon said in a Wednesday memo to campaign staff. “That speaks to both the work you did, and the scale of the challenge we ultimately couldn’t surmount.”

In states across the Northeast and mid-Atlantic, Harris only leads by single-digit margins — far underperforming Biden’s 2020 margins in those states. Signals of Harris’ collapse in the Blue Wall can also be seen in other Midwestern states like Illinois, which Harris carried by only eight points and Biden carried by 17, and Minnesota, which she carried by five points and Biden carried by seven.

Harris is also running behind Democratic Senate and other statewide candidates in both critical battleground states and safe blue states. At least two states, Michigan and Wisconsin, will split their tickets between Trump and a Democratic Senate candidate, with Arizona on track to do the same.

The 2024 campaign has also upended conventional wisdom about campaigning. Harris lost despite raising over a billion dollars — far outraising and outspending Trump — and building up a far more robust ground game. Trump, meanwhile, largely outsourced his field operation to outside PACs, including one run by billionaire Elon Musk. Toward the end of Trump’s campaign, he showed up to his signature rallies hours late and went off on rambling tangents, leaving many of his supporters heading for the exits.

Other polling data illustrates the challenge that Democrats, as members of the incumbent party, had in overcoming a largely pessimistic national mood. A record-high share of Americans — 80 percent — say they believe the nation is “greatly divided,” according to Gallup, which also found that 72 percent of Americans are dissatisfied with the direction of the United States and just 26 percent are satisfied.

In 2016, Democrats still flipped two U.S. Senate seats, six U.S. House seats and a few state legislative chambers. The 2020 and 2022 results were also mixed. In 2020, Democrats captured the White House and Senate while losing ground in the House and state legislatures. In the 2022 midterms, Democrats held the Senate and gained ground in state-level races while losing control of the House, with seats flipping in both directions.

But in 2024, voters have rejected Harris’ candidacy and many down-ballot Democrats across geographic and demographic groups while handing Republicans control of the U.S. Senate and possibly the U.S. House, which as of Wednesday evening, remained too close to call. A New York Times analysis of reported county-level results shows a uniformly red shift across the Eastern, Southern and Midwestern United States, permeating across urbanity, age, race and education.

Counties that are over 25 percent Latinx, less than 50 percent White and more urban saw the biggest shifts toward Trump, The Times found. Counties that are over 90 percent White, over 50 percent college-educated and more suburban shifted toward Trump the least. Counties with large populations of voters 18-34 shifted to Trump by 5.6 points, while those with large 65+ populations moved toward Trump by 4.9 points.

Mel Leonor Barclay contributed reporting.