This column first appeared in The Amendment, a biweekly newsletter by Errin Haines, The 19th’s editor-at-large. Subscribe today to get early access to future Election 2024 analysis.

Five weeks ago, Vice President Kamala Harris was a loyal running mate to President Joe Biden — and both their political futures were in doubt after his disastrous debate performance led to growing calls for him to exit the race.

In conversations about who should replace Biden, Harris was frequently overlooked, her readiness questioned despite her role as his understudy for nearly four years, as critics suggested governors, senators — even Mitt Romney — as a better alternative.

On July 21, Biden finally relented. His announcement was two-fold: he would exit the race and endorse Harris as his heir on the ticket.

Just over two weeks later, Harris is Biden’s clear successor as the 2024 Democratic presidential nominee, having secured the necessary delegates in a virtual vote and making history as the first woman of color at the top of the ticket for a major political party. But the flawless execution, breakneck speed and remarkable enthusiasm around her ascent belies the rocky path to this milestone.

It was a moment that was not a guarantee, but one that was willed into existence by a candidate who is four years and a lifetime away from her 2020 campaign for president, backed by a determined and dogged group of Black women working to write her into history.

It started even before Biden dropped out, as Harris took on a more public role and was increasingly visible across the country on the 2022 and 2024 campaign trail. She became the administration’s main spokesperson on abortion. When Biden stepped aside, Harris spent 10 hours on the phone with more than 100 party leaders. Her immediate pitch to voters, that she was a prosecutor taking on someone with criminal convictions, and the massive fundraising boost that came with her candidacy all but banished memories of her 2020 campaign and concerns about her electability.

California Sen. Laphonza Butler, who has known Harris for more than a decade, said the Harris we are seeing on the campaign trail now “has reached her ‘fuck it’ moment” after facing criticism, ridicule, racism and sexism as the second most powerful person in the country.

“She has come through it all, and when you get to a moment of realizing that whatever you do is not going to please everybody, you’ve just gotta say, ‘Fuck it; I’m going to be the best Kamala Harris I can be,’” Butler said.

In the hours after Biden’s debate debacle on June 27, Harris emerged as one of his swiftest and staunchest defenders. In the days that followed, as donors and high-profile Democrats raised questions about the president’s age, stamina and ability to win reelection, she made the case for his second term, touting the administration’s record as proof that Biden was — and would be — a fighter for them.

But the party was fracturing over Biden’s leadership. And many of the discussions about who would replace him on the ticket bypassed Harris.

Black women in particular were furious.

“Immediately, it was, ‘Let’s make sure they don’t go around her,” said Melanie Campbell, convener of the Black Women’s Roundtable, who organized a letter with more than 8,000 signatures sent to Democratic leadership on July 17 stating their support for the Biden-Harris ticket and reminding Democratic Party leadership of Black women’s power as a voting bloc.

“Black women know the role we play, the influence that we have,” Campbell said. “We had been working hard over these last decades to leverage that, to break barriers. Not ‘just because’ — we wanted to make sure our lived experience is represented in the highest positions in the county that have been dominated by mostly White men. We were ready to fight.”

Veteran Democratic strategist Donna Brazile and Bakari Sellers — who refers to himself as Brazile’s “chief deputy” — worked the phones, each with the same message: They were with Biden, but if he decided to leave the race, there would be no skipping over the first Black woman vice president.

“We came together,” said Brazile, former chair of the Democratic National Committee who started in politics 40 years ago on Rev. Jesse Jackson’s 1984 campaign for president.

“This was not easy, it was not natural, and some of the same people who wanted Joe Biden out wanted her out as well — and that’s when we had to put up an ‘Oh hell no’ moment, internally and externally,” Brazile said.

While the public debate continued, privately, those who knew the rules governing the nominating process were ready for this unprecedented political moment. They wanted to make sure the process for picking the Democrats’ next presidential nominee was fair and that, when it happened, that nomination would be unquestionable.

“At the end of the day, this is a rules issue. They wrote the rules,” Sellers said, referring to women like Brazile and former Democratic National Convention CEO Leah Daughtry, now co-chair of the rules committee. “It was the best primary campaign in the history of the country — and it happened over two or three weeks.”

Daughtry also got her start in Democratic politics working on Jackson’s 1984 campaign, as a coordinator in Hanover, New Hampshire. She’s been a member of the DNC rules committee since 2012.

After Biden’s exit from the race, Daughtry’s task was a daunting one: In an unprecedented moment, how to establish a process that was open, fair and unimpeachable?

“Reverend Jackson taught us … you gotta know the rules in order to change the rules efficiently,” Daughtry said. “What we needed was a process that would protect the integrity of the party rules and that would stand up to this moment which we’ve never had before. The last thing we wanted was for whomever’s candidacy to be tainted by allegations of a closed process that was railroaded through. That would dampen the enthusiasm for anybody who was going to be the nominee.”

Much of the process already in place made the path of any potential challenger to Harris improbable. Candidates would have just three days to throw their hat into the ring, and then another three days to secure the necessary signatures to be eligible for the nomination.

It was a tall order for lesser-known candidates. In the days after Biden’s endorsement, Harris’ potential rivals — seasoned and skilled politicians who may have had more of an infrastructure to contest her candidacy — had already lined up behind her. And West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, who switched his affiliation from Democrat to independent in May, considered challenging Harris, but the rules required that Democratic candidates for president be a member of the party, which made him ineligible.

In the end, it was a moot point: Within 32 hours of Harris declaring her intent to “earn and win” the Democratic nomination she had secured the support of enough delegates to make her the de facto nominee.

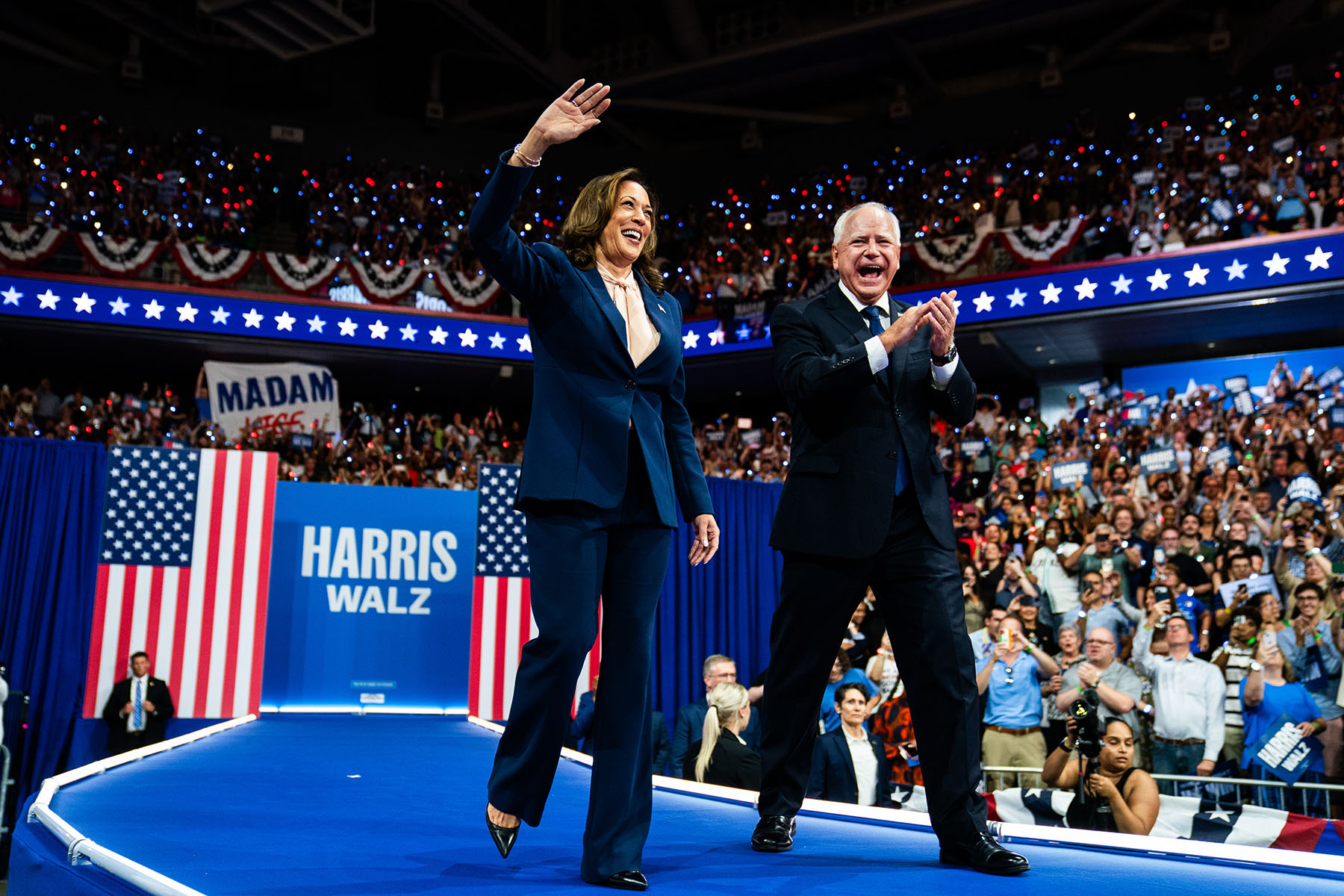

In her debut as a presidential candidate at a rally in Milwaukee, Harris was confident, her message clear, and her delivery enough to quiet the naysayers and excite the Democratic electorate.

Now, as the newly minted nominee, she is pitching her presidency focused on an optimistic vision for America’s future that is a contrast to Trump’s grievance-based campaign.

Harris is also unburdened by past or current criticisms of her leadership and unbothered by personal attacks aimed at her identity, Butler said, adding that it’s an attitude that may also be resonating with voters — particularly women, people of color, and others who have been dismissed or disrespected because of who they are.

“It’s why so many people can identify with the fire she’s bringing to the table; they can identify with somebody who has reached their ‘I’ve had enough’ moment,” Butler said. “Black women have been taking it for a long time. They don’t want Donald Trump to win, but they are also sick of being looked over and passed over. We are not going to miss this moment to be seen and heard and to have a candidate who understands what it means to be a person of color, a woman, to have power, to know that every single day you wake, somebody is trying to take something from you. That is our everyday lived experience.”

Now that Harris is the nominee, these same Black women are moving into the next phase of their assignment: keeping up the momentum to make Harris the country’s first woman president. For some, it is a dream and an assignment not just weeks, but decades in the making.

Marcia Fudge was a recent high school graduate the year Shirley Chisholm ran for president in 1972. Nearly half a century later as a Democratic congresswoman from Ohio, she was among the Black women demanding that then-candidate Biden choose a Black woman to be his vice president.

“There comes a point when you realize that things have changed enough that if you just put more pressure on, eventually that pressure does lead to a change,” said Fudge, now the Harris campaign co-chair focused on outreach and strategy.

“It was somewhat of her destiny — and it was ours to be the conduit,” Fudge said of Harris.

“She did her part and we did ours. We have claimed this victory. We just need to do what it takes to get there.”