This Black History Month, we’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

You may not have heard of Jen White-Johnson. But if you attended the massive protests after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, you may have seen her work. Johnson designed the Black Disabled Lives Matter symbol. The symbol is still present in protests all over the world and, in 2021, was preserved in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture.

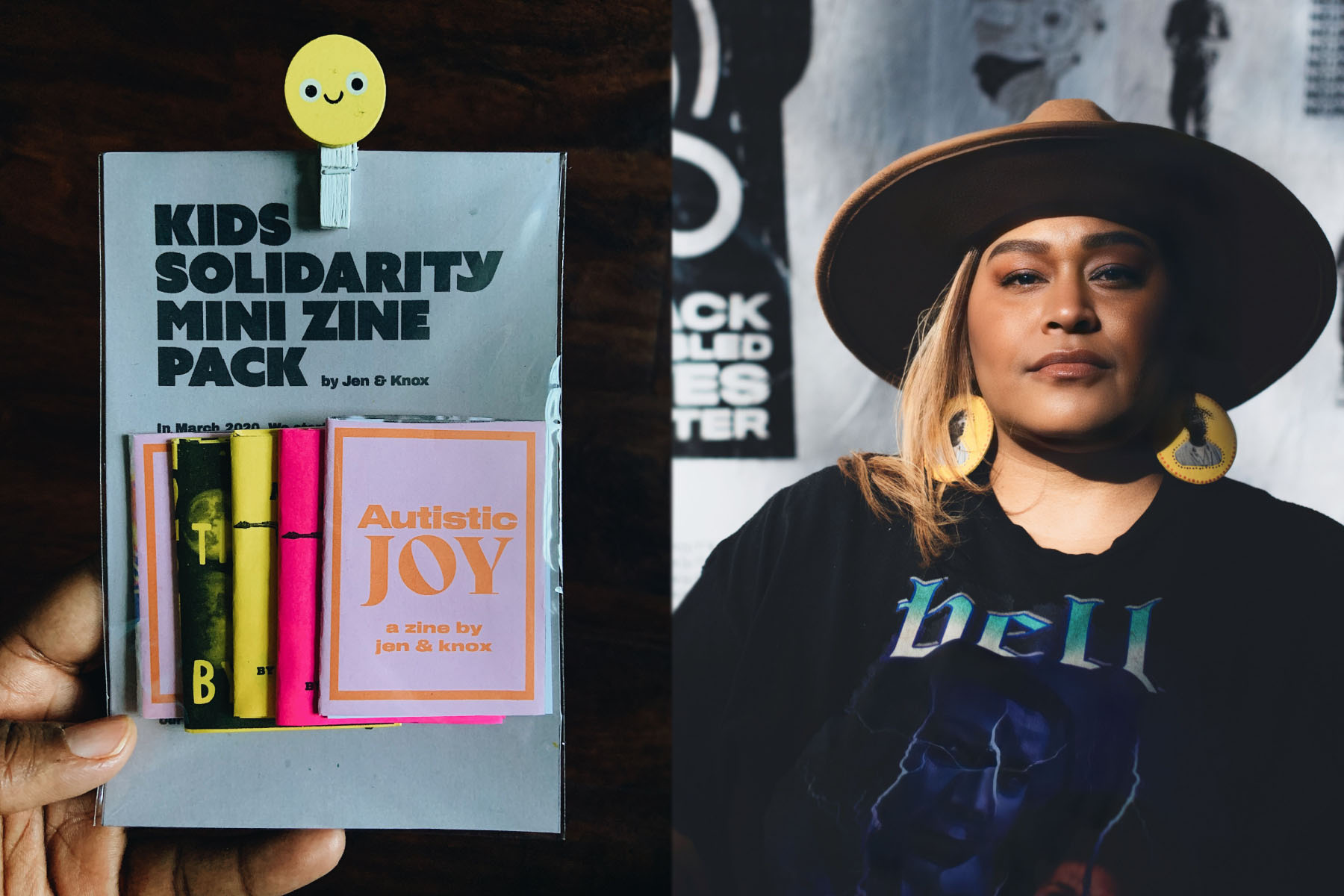

Johnson was born in Washington, D.C. and currently lives in Baltimore, Maryland. She is an artist, activist and prolific zine maker. She has produced zines on everything from mothering a Black, autistic child to climate justice. Her most recent zine is focused on reproductive justice for Palestinian women in the latest eruption of the Palestine-Israel conflict, in which around 1,200 Israelis and over 30,000 Palestinians have been killed. For Black History Month, The 19th sat down with Johnson to discuss zinemaking, parenting, solidarity and the role of art in the disability justice movement.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get interested in zinemaking?

I love zinemaking because it’s such a democratic way to create. I’ve never really been a standard design firm, corporate kind of creative, and I love being able to create my own boxes. It’s always been difficult, and a lot of that has to do with my ADHD and undiagnosed autism. A lot of neurodivergent people love very linear jobs and very rote-based kind of approaches to their work, but I love being able to bend things. I love being able to explore multiple worlds of how to make something.

I love that zinemaking can be approached in a very non-practical, flexible, free way. It’s very similar to jazz.

I studied design at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and then I got my graphic design degree from the Maryland Institute College of Art. I’ve always thought, what are the stories that are missing? What are some of the things that are really speaking to me? I knew that I didn’t want to just pick one specific design path. Zinemaking is one of the spaces where I can combine so many different mediums and art styles. I can turn them into something beautiful, liberatory and democratic.

To me, zinemaking has always been a culture of rebellion, of collective liberation. It’s not held back by any kind of capitalistic norms. Zines are punk rock.

Do you remember the first time you saw a zine?

My mom would create these really small cards for me. They were essentially little love letters. She started making a lot of them when I had gone away to college. I would come home and she’d give them to me or she’d mail these small little love letters and cards. I consider those the first zines I ever saw.

They were these little notes that would be passed along to kind of remind me of how unique and special I am. She didn’t really understand my undiagnosed ADHD at the time, but we had our own ways of being able to communicate with each other.

Later on, once I got into design, I realized they were zines. They were like the Riot Grrl zines or feminist zines I read later that were photocopied and created with a typewriter, that I got at festivals or concerts.

Those zines were some of the first things that contained narratives that I resonated with, about femininity and chaos. I got to see a lot of feminist voices that were being co-opted or erased.

How does your son, Knox, inspire you and your process?

I became a mom at 31 or 32 years old. The Freddie Gray uprisings, the Mike Brown uprisings were happening during those early years of my mothering journey. There was so much injustice being done against Black and Brown bodies.

When he was born, he was two pounds. He was a micro preemie. That shifted a lot for me. When he was diagnosed as autistic in 2015 I was like, okay, I’m in this world. All of these unjust signals are being thrust at me. As a parent and as a designer I felt like my role was pretty clear. I wasn’t seeing a lot of celebratory stories. I wasn’t seeing narratives rooted in disability joy, especially from the Black and Brown neurodivergent experience. When your kid is autistic, a lot of what is thrown at you is like, “What are you going to do to normalize your child? What are you going to do to get them fixed so that they can be a valuable asset to society?” versus “How can we cultivate beautiful systems of support and love?”

Because a lot of what I was doing was already very much rooted in justice work and movement work, I was like, “Hey, I need to be able to translate all of that.” I needed to be able to build justice into how I defined mothering, how I’m building a positive relationship with my son. He inspired me to be myself and to show up, very unapologetically.

From when he was born and until he was about 6 years old, I would just document him, follow him with a camera, because I wanted to just create something and I wanted to just let his natural, authentic autistic joy shine through.

Autism had really only really been pushed on me in very negative ways. I was grappling with my own undiagnosed ADHD and my own undiagnosed autism and not really inspired. He made me more free to be able to disclose those disabilities and to feel safe. Mothering became this beautiful space of resistance. I was chipping away at all of those barriers that I placed on myself, that society placed on me.

I let the art and design shift and let it speak very unapologetically about what disability joy was, to hold space for him. I feel like he really helped inspire the artist I felt like I always wanted to be. He helped me break free.

You’ve written about the importance of following the work and wisdom of Black disabled creatives, activists and ancestors. Whose work and wisdom inspires you the most?

Fannie Lou Hamer is a big one. She had so many access barriers. Surviving polio as a kid impacted her mobility. She was out there, galvanizing folks to get out the vote, and to hold spaces for folks to be able to get the access to vote, running for office and not letting anything stand in her way. Even though she was victimized and dealt with reproductive injustice and forced sterilization – that was so common among so many Black women —- she adopted children, and she was able to be this really beautiful mother of communities. If we’re not creating spaces of freedom for ourselves, then how are we going to be able to create those spaces of freedom for other folks?

Disabled narratives get left out, especially Black disability. Black disabled ancestors have helped pave the way for us, whether it’s Fannie Lou Hamer, or Harriet Tubman, or Lois Curtis. … Those were people no one was really schooling me or walking me through. Knox inspired me there, too. Because I’m an educator, I wanted to do as much research as possible to learn about my culture, to learn about my history to form relationships. I wanted to learn what I needed to show up in various spaces where folks could feel safe and free to express behavior they’d been held back for.

You designed the Black Disabled Lives Matter symbol in 2020, in the wake of the George Floyd protests. How did it come about? And four years later, how do you feel about the legacy of the symbol you created?

I felt like I had to answer the call. There was a lot that wasn’t being said about Black disabled voices and a lot that was being left out. We were being left out of disabled narratives. But the reason a lot of Black and Brown folks were being victimized and dehumanized was in part because of their disabilities. Disability just added fuel to the fire.

Black disabled folks get locked in cages. We are consistently misunderstood. We’re dehumanized. We’re objectified. We’re viewed as crazy or angry when really, we need support. All of those conversations were consistently being left out of the narrative of Black Lives Matter. I felt like not enough Black disabled folks were being put in positions of authority to help lead these conversations.

I used art to combat injustice because it is the voice that I speak in. I wrote an essay in An Anthology of Blackness, examining the state of Black design and how Black designers are erased in conversations. We’re erased in the cultural iconography, logos, products, stories and films that we’re creating. We’re making spaces and we’re building conversations that we need to have more of. Design can empower us and help keep our culture alive.

I decided to play with a Black Power symbol and created something that really helped to intersect the conversation on Black neurodiversity, and neurodivergent culture. I wanted to make sure the word “disabled” actually shows up in the art, that it was not erased from the conversation. I really just created it for my Black disabled friends like Imani Barbarin and for folks like Anita Cameron and Leroy Moore, folks who had been part of this journey for a very long time.

It was really just a creative reaction, a creative response. I am just so thankful that so many different disabled folks shared it and were amplifying and uplifting the symbol, and then it just continued to spread. It’s been shared all over the world.

I felt like the symbol helped contribute more visibility to the conversations that were already being had. I just played a part in a huge movement that was here before I was even born and that will be here long after I’m gone.

Your most recent zine project is focused on Gaza and solidarity with the Palestinian people. Tell me a little bit about it?

My first zine project in 2018 was dedicated to Black disabled joy, particularly involving my son. I wanted to amplify what Black and Brown autistic joy looks like. That theme helped pave the way for smaller, more intimate mini zines, designs and stories. I’ve done zines about climate injustice and how it intersects with disability justice.

This latest zine is about Gaza and holding space for the thousands of pregnant women who have been killed in Gaza, who have lost their lives because of inadequate access to health care, because of being displaced or having their entire neighborhoods bombed.

Some folks write articles, some folks are podcasting, blogging, doing Instagram Live or a TikTok reel. They’re helping to get the truth out there. I use zinemaking and design to make it visually accessible, so that folks can actually have a piece of art, a piece of something they can download and print or mail.

The zine is called “To Gaza, with Love.” I wrote an essay to help to encapsulate my thoughts on how important it is to remember so many lives that have been lost, but that there’s a fight for liberation [shared by] Black and Brown folks and Palestinian folks. That fight, the need for conversation and for unity has existed for a long time.