Your trusted source for contextualizing justice news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

In the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, the country saw its largest decarceration effort in history. Dozens of psychiatric hospitals and large state institutions around the country that acted as warehouses for people with disabilities closed after public outcry and a series of lawsuits aimed at improving conditions. Over subsequent decades, the number of people in the institutions decreased by tens of thousands.

Today, advocates for disability justice and reducing mass incarceration can draw on that history, said Liat Ben-Moshe, an assistant professor of criminology, law and justice at the University of Illinois Chicago and author of the book “Decarcerating Disability.” These two movements — which are primarily led by women, queer people and people of color — can build coalitions and recognize their common threads.

“There is kind of like a siloing that’s still happening,” Ben-Moshe told The 19th. “I think the larger public, and people who do decarceration work or criminal justice work that is not related to disability, may not see how these institutions are connected to their own rights and research and policy.”

For people in the disability justice space, carceral facilities and disability have long been linked.

People with disabilities currently represent about 40 percent of incarcerated people overall, and nearly half of incarcerated women, according to government data. This is likely an undercount because it is based on self-reported numbers.

The country has a history of normalizing forced detention for people with disabilities, similarly to how society has normalized punitive responses to people accused of crimes, said Dom Kelly, founder, president and CEO of the advocacy group New Disabled South. Changing this approach to institutionalization required a significant shift in policy and public awareness, as well as efforts to reimagine care for people with disabilities outside of these massive institutions, Kelly added.

-

Read Next:

“We’ve reimagined what this could look like for disabled folks, so we can reimagine what it looks like for everyone,” Kelly said. “I think our government can start to think about how we invest in improving people’s lives and in things that actually are proven to decrease interactions with policing and the carceral system.”

The population of people with intellectual or developmental disabilities — or both — in large residential institutions peaked in 1967, with 194,650 people living in these facilities, according to research. That number dropped by 64 percent to 69,557 people in these institutions by the year 2015.

Similarly, the population of people with psychiatric disabilities in large state mental institutions saw a notable decline from 559,000 people nationwide in 1955 to fewer than 100,000 people by 2000. These institutions were often fraught for women and LGBTQ+ people, who endured traumatic treatments seeking to “cure” them.

Many women were forced into institutional settings for behavior or beliefs that differed from the mainstream society’s standards. For example, in the late 1800s the Magdalene Laundries were Catholic-run penitentiaries that housed a range of women and girls deemed to be “fallen”: unwed mothers, victims of sexual abuse, or people with physical or mental disability.

“What the Magdalene laundries taught us is that women didn’t have to commit a criminal offense to be locked up in an institution unable to leave for the duration of their adult life,” said Michelle Daniel Jones, a fourth-year doctoral student at New York University, who spoke to The 19th about the laundries in March.

In the late 19th century, the rising eugenics movement further fueled a climate of exclusion and abuse by preaching the eradication of “undesirable” people, including people of color and those with disabilities. Between the 1860s and 1970s, so-called “ugly laws” outlawed people’s ability to appear in public based on their appearance. Chicago’s law banned any person “who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object.”

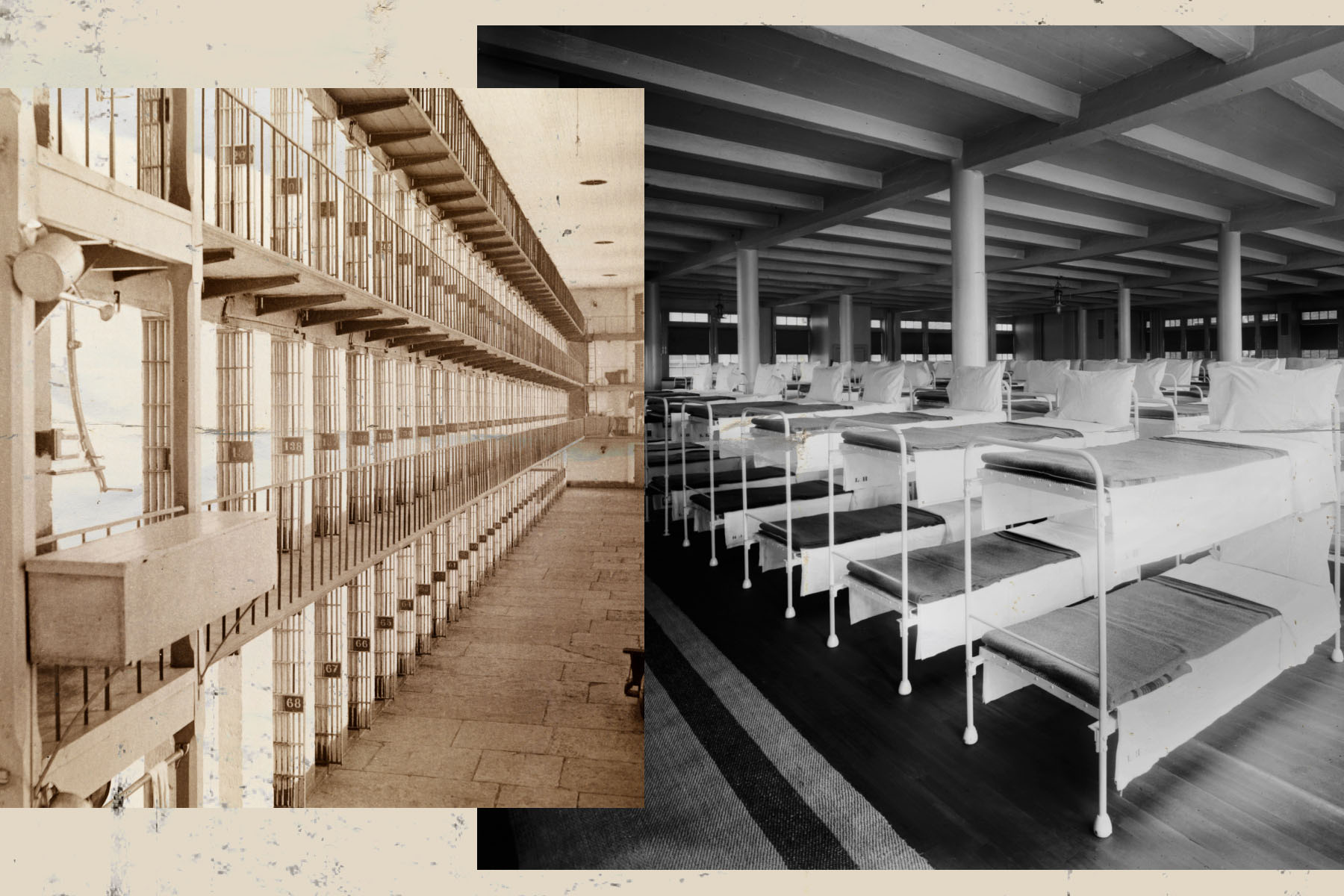

That mindset affected how society overall thought of people with disabilities, including in residential and medical care. Institutions faced overcrowding, understaffing and a lack of funding that fostered abuse, dilapidated conditions and poor support for residents.

The closure of institutions came about due to a “perfect storm” of factors: new legislation, a wave of lawsuits and financial constraints, Ben-Moshe wrote in her book.

President John F. Kennedy signed a landmark bill in 1963 that sought to establish community health care centers that were required to provide inpatient and outpatient services, mental health education, crisis response and partial hospitalization. Kennedy’s program ultimately did not create many of these centers, but the development of Medicaid and Social Security Disability Insurance in the ‘50s and ‘60s also helped to promote alternatives to large institutions.

Journalists played a role in changing public sentiment about large institutions as well. The most famous example is a 1972 expose by Geraldo Rivera, who brought cameras into the Willowbrook facility for disabled children in Staten Island. Dr. William Bronston, a physician there who coordinated to allow Rivera into the building, described it as “pandemonium all the time, shrieking, stench, chairs flying, people unconscious, asleep on the floor after being drugged daily,” Ben-Moshe recounted in her book.

The resulting public outrage prompted legal action, which led to closings of institutions, said Jasmine E. Harris, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School with expertise in disability law and antidiscrimination law

“These institutions were so underfunded that they had to close. There was no way that they could survive because the types of reforms that were requested were going to be too costly,” Harris said.

In many ways the story of deinstitutionalization highlights the power of public pressure and legal action to drive movement toward change. But changing laws has limitations, Harris added. Involuntary confinement remains a problem for older people and disabled people in the form of facilities like privatized nursing homes, group homes and through legal contracts like conservatorships. People with disabilities are also disproportionately criminalized, making them more susceptible to going to prison or jail.

One popular theory asserts that prisons and jails are the new asylums, or that deinstitutionalization led to the rise of mass incarceration due to the overrepresentation of people with disabilities in jails and prisons.

-

Read Next:

This idea overlooks a more complicated reality that involved large cuts to social welfare programs in the 1980s and the expansion of policing, Ben-Moshe said.

“This is a dangerous claim, it’s not just a wrong claim, because this leads people to say, ‘The way that we fix the criminal justice system is, for example, by reopening the psychiatric hospitals that closed,’ she said. “People fought so long and so hard to close down these facilities.”

An important step for decarceration activism today is to recognize and address forms of detention both inside and outside prisons and jails, Ben-Moshe said. Disability justice and decarceration organizers need to understand dynamics of the carceral-industrial complex. This term, more frequently called the prison-industrial complex, refers to the extensive network of industries and institutions that support the carceral system.

It speaks to the ways that local economies can depend on prisons or other facilities, as well as how racism, ableism and other means of marginalization are woven into these industries. For example, research indicates that prisons not only tend to be built in economically distressed communities in the South, but they are also built in towns that have higher Black and Latinx populations.

When proposing solutions to these systemic issues, political conversations about deinstitutionalization in the past — like many conversations about decarceration now — focused on improving the conditions of detention rather than recreating one that invests in solutions to address communities’ socioeconomic, medical and environmental needs, Harris said.

“We’re looking at the criminal justice system apart from the social welfare system, and that’s a mistake,” Harris said. “The way in which we structure the social welfare system intimately relates to this question of how we design a world where we avoid people being moved from one form of confinement to another.”

Investment from government officials and policy makers can assist with this redesign, researchers told The 19th. Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the country saw a larger movement to reduce prison and jail populations. Figures collected as part of the Jail Data Initiative at New York University’s Public Safety Lab found that daily jail populations collectively declined by about 27 percent between March and May 2020. For women, jail populations declined by 42 percent. This was a result of fewer arrests and targeted releases for certain offenses.

But many decarceration proposals focus on incarcerated people charged with nonviolent crimes, who are more likely to have broader public sympathy. Though it is controversial, Ben-Moshe said she believes it’s important to start with supporting individuals who have the most complex needs, which can include those who have committed violent crimes.

The government’s hesitation to make more broad, radical change has created a cycle of incarceration and detention for historically marginalized populations that plays out today.

For example, the initial COVID-related decarceration push was short lived and many cities and states have returned to “business as usual” rather than identifying ways to sustain their practices, researchers previously the The 19th.

When it comes to disability, last year California enacted the Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment Act to establish a court system where loved ones, first responders or behavioral therapists can petition for a person experiencing a psychiatric crisis to complete a mandated treatment program for up to two years. Last year New York City Mayor Eric Adams signed a directive to reinforce the government’s power to detain and hospitalize “a person who appears to be mentally ill and displays an inability to meet basic living needs, even when no recent dangerous act has been observed.”

Eric Harris, director of public policy at Disability Rights California, is one of a number of advocates who feel such proposals are taking steps back toward institutionalization. Disability Rights California supports people being able to make their own choices about the medical care and treatment they receive.

Harris said he recognizes that there may be family or friends who genuinely want to help support a loved one in crisis. Community based programs that build trust and rapport with people and offer services like housing and mental health resources.

“It is often a default to put somebody who’s going through a crisis or somebody who is unhoused in an institution of some form,” Harris said. “Many say what was happening decades ago is still happening in many ways today.”