In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as the civil rights movement and anti-war movement were continuing to raise the alarm about the inequality that was impacting — and literally killing — the most marginalized Americans, there was a growing women’s movement that was being informed by what they saw and experienced around them.

Though it is not often written about, Seattle was the site of several women’s liberation groups that were formed to advocate not just for women’s rights, but an end to racial capitalism and imperialism.

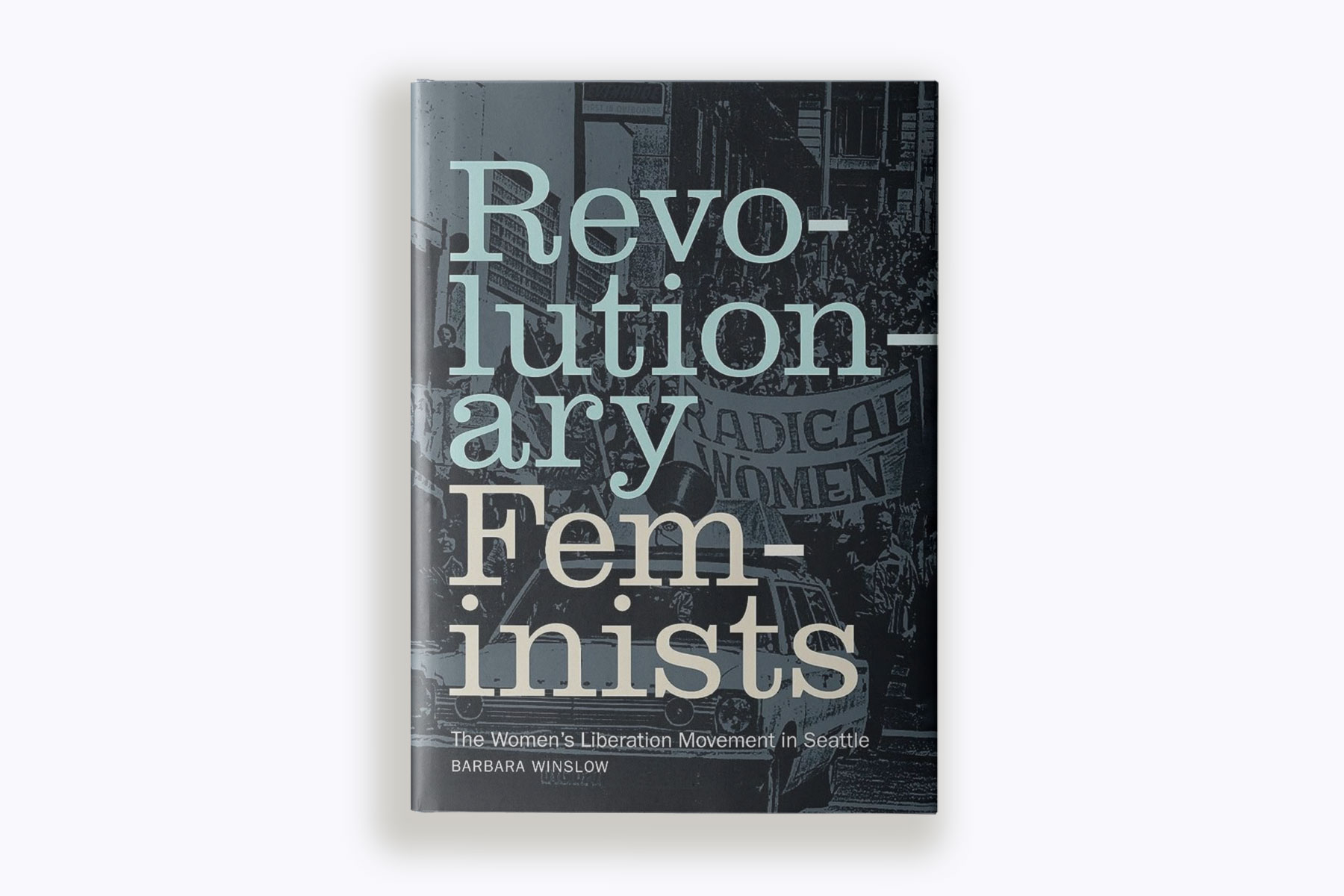

Among those involved in this movement was Barbara Winslow, a historian and professor in the School of Education at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York (CUNY). A founding member of Seattle Radical Women and Women’s Liberation Seattle, Winslow saw firsthand the impact of being involved in one of the few multiracial feminist organizations with women of color in leadership. In her recently released book, “Revolutionary Feminists,” Winslow seeks to detail the history of the women’s liberation movement in Seattle, but she also challenges readers to think about what histories have gone untold in their own communities.

The 19th recently spoke to Winslow about her book and the lessons of the women’s liberation movement.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Rebekah Barber: As you mention in your book, not much has been written about the women’s liberation movement in Seattle. Why do you think this is?

Barbara Winslow: I think there are a lot of reasons. I think part of it has to do with what I would argue is big city chauvinism. I write in my introduction that most has been written about New York, Boston, Chicago, and Washington, which are all major cities.

Part of it is the provincialism of a lot of historians. One of my hopes is that people reading

this book might say, “Just a minute, Barbara Winslow, I know we had a rape crisis clinic set up in ’69. We beat Seattle.” Or they might say, “This book in Seattle is interesting enough. Let’s see what happened in Durham [North Carolina] or other places that are not major cities.”

As someone who was deeply involved in the women’s liberation movement in Seattle, what was the experience of documenting this history like?

I’m 78. I don’t mind to say my age. Today, more and more historians, like myself, should say, “As you write this history, perhaps the fact that you were White and privileged or that you were Latinx and constantly hounded by the authorities, how does your lived experience help you interpret even the factual information?”

I certainly hope that while I was very engaged, I interrogated — and I think I do in the book — my own privilege. I was White, upper middle class, I got a good good education, I have good health. I have all the advantages — and I think you have to look at that.

I can say the other thing is because of this, until I started doing the research, and I found out, for example, that the first 10 years of our Women’s Studies program at the University of Washington, there were no Black women teaching. There were no courses on Black women.

That’s why I say you have to really think about the position you’re in when you’re writing a book.

Women of color, in particular Latinas and Black women, played foundational roles, both in the women’s liberation groups that were overwhelmingly White, but also they founded African-American groups.

In your book, you make a distinction between the women’s movement and the women’s liberation movement. What does this distinction entail?

I will credit Alex Kate Schulman with that understanding. The women’s movement refers to the more mainstream middle class, within the Democratic Party or in the language of 1968, bourgeois women’s movement.

I would argue that their feminism, that is the belief in women’s rights, did not challenge an existing racialized patriarchal system. Those of us on the left — the word I use [is] radical or revolutionary or left feminists — were the women’s liberation movement because we felt that it wasn’t just women’s rights.

We wanted an end to patriarchal racial capitalism. We were anti-imperialists, and we wanted our personal lives to be liberated from the strictures of what we refer to in today’s language as heteronormative behavior.We felt that women should be in whatever kind of relationships they want — lesbian, gay, etc. I think that was a very fundamental difference.

One thing that you point out was that there were a lot of different women’s groups organizing in Seattle at the same time. In what ways was this a good thing? Were there any downsides?

In any social movement, there are a wide range of different groups. I’m old enough to have lived through the civil rights and Black freedom struggle, and there were a myriad of groups. The fact that there were more groups with different political perspectives was a good thing. It means that, for me, I learned about a wide range of political strategies and issues. I think we all did.

We also had to learn how to work with groups with which we didn’t have a lot of agreement. We had to learn how to negotiate. I think that’s positive. The fact that there were so many groups was also indicative of the fact that the movement was large, which is also positive.

Now, a negative thing, which I’m sure comes out in the book, because I write about, is what I call the factionalism.

I’ll give you [an] example, which is one of my favorite stories. It’s in the book. We all were very critical of Gloria Steinem. I didn’t mention in the book, but when she generously invited us back to her room [after an event], we had a screaming argument with her.

When she came to speak at Brooklyn College, where I teach, she was the first keynote speaker on Shirley Chisholm Day because she’d worked with Chisholm.

I told Gloria, “I’m going to mention this.”

I could tell my students were looking at me going, “Barbara Winslow was screaming at Gloria Steinem. How could anybody scream at her?”

She laughed, and when she spoke, she was really generous. She said, “Barbara, those differences were important, because we felt we had a world to win.”

As you look back, what are some of the things that you wish that the women’s liberation movement in Seattle would have done differently?

Did we make mistakes? We sure did. Everybody, every movement does. Not only was I a participant, but I’ve studied the civil rights movement, and you could talk about the mistakes [Dr. Martin Luther] King and other leaders made. But in the broader scope of things, the mistakes we all made were not all that significant in the context of the defeat of the left.

However, I will say that looking back, those of us who were struggling for reproductive justice never imagined the pushback on abortion rights and birth control. We never imagined that people would murder doctors, nurses and health care workers. We never imagined they would blow up clinics. It was just unfathomable.

But I think the main mistake we all made is we really did not appreciate the nature of the period and the defeat of the left. We really thought we were on our way to racial, class and gender justice. It seems that we were unstoppable.

After Nixon got elected in ’72, by a landslide, even in ’72, with all the excitement of the Shirley Chisholm campaign, we didn’t realize how badly defeated the left had been and in particular, the Black liberation struggle.

Especially as it relates to reproductive justice, so many fights you all were waging then continue today. What are the lessons you want people to glean from the book?

First and foremost, the history of the women’s movement and the women’s liberation movement has been poorly written, badly written and erroneously written.

For example, I was listening to the head of NOW [the National Organization for Women] who was going on and on about how one of the mistakes they made was not to fight to make abortion accessible, but radical feminists did.

All the clinics we set up were to make abortion accessible, but we were a minority. After ‘’72, organizations like NOW and NARAL looked to the center of the Democratic Party and looked to the courts.

Hopefully from reading the book, people get a sense that it’s the local struggles at this moment that count. If you believe in electoral politics, run for your school board, run for your city council, keep it local.

If you don’t like electoral politics, which many people on the left don’t, build your reproductive justice group, build your group that fights racist police brutality, build your climate justice group, keep it on the grassroots because one thing that I learned from the ’60s is the reason that so much good legislation passed, even from somebody as awful as Nixon, was that there was a movement that was pushing politicians’ feet to the fire — and that’s what we have to start rebuilding again.