Members of the military community struggle with starting and growing families at far higher rates than their civilian counterparts. About one in every eight couples in the general population face challenges while conceiving, according to Resolve, the National Fertility Association, and that doesn’t include many LGBTQ+ couples who also wish to use assisted reproductive technology to start and grow families. But according to the 2021 Blue Star Families annual lifestyle survey, more than two-thirds of the military community report challenges to building a family.

Julie Eshelman and her husband, an active guard reserve soldier, struggled to start a family. Eshelman said they started investing in ovulation test kits and eventually tried to see a fertility clinic physician. But the waitlist was over a year long, and the couple knew they would be transferred to another base before then. The time crunch, on top of the lack of insurance coverage for infertility treatment, felt increasingly onerous as months of trying turned into years.

“There was a whole year where my husband was gone every time I was in my fertile window,” said Eshelman, who said her experiences led her to volunteer with Resolve. “If we’re not together, we can’t get pregnant. We’ve come to accept that as family, but it also makes it hard to pay for these things out of pocket when I can’t have a career, or it’s very challenging to have a career that can move with me.”

The military lifestyle presents a unique set of challenges to family building, including unpredictable separations between partners, disruptions to medical treatment due to relocation or deployment, and lack of insurance coverage for certain care. More than 10 percent of active-duty respondents said family-building challenges are a main reason why they’d leave the military, according to the Blue Star Families, which was founded in 2009 by military spouses.

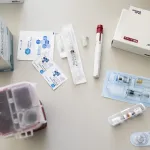

Eshelman, now 36, said in the past several years, they’ve moved four times, suffered several miscarriages and spent up to $40,000 out-of-pocket for intrauterine insemination (IUI) and in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures, embryo storage and medications. The cost of IVF at a military hospital averages around $5,000 for each attempt but can be as much as $10,000 if it includes freezing embryos or involves a donor. The cost of IUI, a less invasive procedure, is much less expensive, at about $173 per attempt.

Barbara Collura, the president and chief executive of Resolve, said the government falls short in taking care of its military community — people who’ve volunteered to protect the country — when it comes to the issue of family building. Currently, only six military facilities offer IVF treatment, though patients are still required to pay out-of-pocket. If a service member or their spouse is not located near one of these facilities, they have to use vacation time or get permission from their command to take leave.

“It is mind boggling that we are making it so hard for our service members to access reproductive medical care,” Collura said. “It’s a huge problem.”

Collura said the solution is simple: insurance coverage. She said that is the number one priority that she hears from people around the country. TRICARE, which covers people across all the military services, offers some infertility care treatments, but only those considered “medically necessary and combined with natural conception.” Artificial insemination and any costs related to donors, semen banks or “non-coital reproductive procedures” are not covered unless the service member is married and sustained an injury while on active duty that resulted in the loss of “natural reproductive ability.”

“TRICARE needs to treat infertility like any other disease,” Collura said. “They need to provide comprehensive care and access not just to a handful of military treatment facilities, but where service members can get care wherever they are. How do we ensure that our service members have access to everything they need to build a family — whether through adoption or medical treatment? This particular dream should not be taken away from people just because they joined the military.”

Even in the civilian population, fertility care is often inaccessible to many because most public and private insurers do not cover these treatments. Most people pay for IUI and IVF procedures out-of-pocket. As of June 2022, however, 20 states have passed laws that require some private insurers to cover some fertility treatment — with 14 of those laws explicitly including IVF coverage.

Service members and their spouses also face extra administrative hurdles when it comes to insurance as cross-country moves often mean switching plans and finding new medical professionals.

In one move, Eshelman said she and her husband had just found out they were pregnant via a successful IUI procedure. They were moving to a new station — driving from Phoenix to Illinois — when Eshelman started experiencing severe cramping. After seeking help at an emergency room, the couple was informed that she had miscarried.

“It was a nightmare,” Eshelman said. “The insurance carrier for the military is divided into two regions: the east and west. We were switching from one to the other, and I couldn’t get a primary care doctor assigned to me until my husband checked into his new unit — and we were still four days away from our final destination. The emergency room doctor wanted me to be seen by my gynecologist the next day, but it was over a month before I got any follow-up care.”

Access to fertility care across the board — particularly IVF treatment — was further complicated in recent years due to COVID-19, which forced clinics to postpone appointments in 2020, and the fall of Roe v. Wade in June 2022. As states began to pass abortion restrictions that defined life as starting at fertilization, medical professionals and reproductive advocates worried that access to IVF might be negatively impacted.

Eshelman said she was living in a mountain town of 5,000 in Pennsylvania when the Supreme Court overturned Roe. The nearest big-box stores were about an hour away, and Eshelman said one of her first thoughts was how the decision would impact her ability to build a family.

“So we’re thinking: How is this going to affect us?” Eshelman said. “Are they going to pass these laws? How is that going to affect IVF? How is this going to affect miscarriage care?”

After moving four times in five years, Eshelman said she was worried about navigating a new landscape where the status of reproductive access and even the definition of conception differed across state lines. She told The 19th in late March that she was waiting to see whether a clinic in Pennsylvania would accept the couple’s embryos from Illinois.

Collura said her team continues to monitor state legislation closely, but as of April 2023, no state has passed abortion bans that explicitly prohibit IVF treatment. But, she added, it will take time to see if there are inadvertent impacts on IVF access as clinics respond to the enforcement of these laws when it comes to the treatment and testing of embryos.

Despite the uncertainty of the last few years, Collura said in her more than two decades working with Resolve, she has noticed a growing public awareness and interest in treating infertility. Members of Congress are starting to talk about it, and the Pentagon is starting to put more of a focus on supporting military families. The Army, for instance, issued a directive in 2022 to address fertility treatment, pregnancy and postpartum recovery.

Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, a Democrat and veteran, introduced a bill on April 25, marking National Infertility Awareness Week, that would require the government’s health insurance program to cover assisted reproductive treatments and services, including IVF, for all federal workers.

“I would not have my two girls without it,” Duckworth told The 19th. “Without the miracle of IVF, I wouldn’t be a mom today, and there’s so many other people like me who might never have been able to start a family without IVF.”

Though the proposed legislation would not impact members of the military community — who are typically covered by TRICARE — Duckworth said she continues to urge the Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to improve access to assisted reproductive technology.

“The VA already provides assisted reproductive technology to some veterans, particularly males who lost their reproductive organs — there are a lot of people who were wounded by stepping on landmines in Afghanistan for example,” Duckworth said. “And so we’re moving the needle and making sure that we get to a point where a soldier like myself could freeze her eggs in her 20s and 30s when overseas and on deployments. That sort of thing should be covered.”

Collura said she’s seen change happen in the private and public sector, outside of the military, when people speak up. Resolve works to motivate employees to advocate for themselves. In the last several years, Collura said, more than 2 million people gained insurance coverage for infertility treatments through their employers just by asking for it.

Eshelman said she didn’t start openly talking about her experience with infertility until after suffering a third miscarriage while her husband was away for a drill weekend. She had heard a heartbeat in the fertility clinic, but when she went to her obstetrician for an initial appointment, there was no heartbeat and was told that a surgery was necessary.

“Up until that point, nobody knew we were struggling,” Eshelman said. “Nobody knew we were dealing with infertility. Nobody even knew about the first miscarriage … When we really started to open up and share, I began realizing that I knew people that had also had miscarriages or were quietly struggling with infertility.”

Eshelman said she became involved with Resolve in 2020, when they made their federal advocacy day into a virtual event due to the pandemic, but she quickly realized that the organization’s outreach and infrastructure was not set up to capture the military perspective. Eshelman knew she wanted to change that: In the last few years, a military and veterans task force subcommittee was created to target the recruitment of military advocates.

“We can ensure that lawmakers are hearing from the military community on these infertility and family-building issues,” Eshelman said. “We’re also hoping to empower those delegations that don’t have a military-connected advocate on how they can better advocate for our community.”

In December 2022, Resolve launched a monthly support group, led by Eshelman, for those struggling with infertility in the military. About a dozen service members, veterans and spouses meet to share ideas, support and resources.

“A lot of times, when you’re struggling with infertility, people that don’t understand it say things that are hurtful,” Eshelman said. “It hurts, and we can be frustrated by that. A lot of people are going through this in secrecy, and they don’t have anywhere to turn to. The number one thing I’ve heard since we started the support group was that people wish it was here sooner.”

After five years of tests, treatments and surgeries, Eshelman and her husband delivered their daughter in June 2021. They continue to pay out-of-pocket for IVF treatments as they try for more children.

“Consider what our military families sacrifice and what our veteran families have sacrificed and given up and put aside,” Eshelman said. “I’d like to see Congress consider and cover these treatments to make it easier for us to build our family.”

Recommended for you

‘This is our new normal’: Fertility treatment advocates are gearing up to fight abortion bans and personhood laws