We’re answering the “how” and “why” of education news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

Gender theory. Ethnic studies. Intersectionality.

If Florida’s House Bill 999 passes, students at the state’s public colleges and universities would be prohibited from majoring or minoring in these academic disciplines as well as in related fields, including queer theory, critical race theory, feminist theory and social justice.

“The fields that are being threatened are fields that challenge the status quo, and these are well-established, respected disciplines,” said Irene Mulvey, president of the American Association of University Professors. “They enrich academia. They enrich our civilization, but they’re being dragged into the culture wars now. And I feel like these bills are an attempt by people in power to maintain the status quo . . .at the expense of a free and open democratic society.”

Wording in HB 999 has also sparked fears that it could threaten sororities, fraternities and other clubs on campus that cater to Black students and other students of color. Currently in the Florida House’s Education and Employment Committee, HB 999 will take effect July 1 if enacted. Along with its companion legislation in the Florida Senate, the bill is one of the latest introduced in a state that has passed a series of recent laws to limit what students can learn about race, gender, sexuality or inequity.

Another piece of legislation in front of the legislature, HB 1069, would restrict what can be taught in sex education courses in Florida’s public schools, so that abstinence is emphasized and students learn that sex is determined “by chromosomes, naturally occurring sex hormones, and internal and external genitalia present at birth.” Florida’s HB 1223 would prohibit use of pronouns that don’t match a child’s assigned gender at birth and has been described as an expansion of legislation commonly known as “Don’t Say Gay.” Both of these laws would also take effect in July, if enacted.

Educational gag orders — which is how free expression advocacy group PEN America describes legislation that limits lessons on certain topics — typically target K-12 schools. Most states have introduced such bills over the past two years, and House Republicans last month passed the Parental Bill of Rights Act, which echoes legislation filed at the state level and purports to give parents a say in their children’s education. This includes access to learning materials, school board meetings and conferences with teachers — rights educators note that parents already enjoy.

Increasingly, PEN America research has found, educational gag orders focus on higher education, indicating that these policies intend to do far more than expand parents’ rights over their minor children’s education but to broadly limit free thought.

“Most of us understood that what was happening in K-12 was going to find its way to higher ed,” Mulvey said. “It’s extremely concerning because the difference between K-12 and higher education is that in colleges and universities, students and faculty are free to follow their interests wherever they lead. That’s what makes American higher education globally preeminent. This system of higher education, where robust academic freedom is enforced by disciplinary norms and professional standards and peer review, is what makes higher education a driver of the economy and has given us great breakthroughs.”

While critics of legislation such as Florida’s HB 999 warn that it is dangerous, they are also optimistic that, if passed, it would ultimately be struck down in court as unconstitutional due to long-standing legal precedents that protect academic freedom in higher education.

HB 999 has not only raised concerns because it would limit what college students can study but also because it would allow state university boards of trustees to review the tenure status of faculty members, a provision the legislation’s detractors say could have a chilling effect on the free speech of educators.

Jerry Edwards, staff attorney with the ACLU of Florida, said the legislation puts tenure in the hands of political appointees, which significantly lessens job protections for faculty.

“I think the goal is to chill speech that our leaders in the state government disagree with,” Edwards said. “I don’t think that’s something anybody should want because, first of all, leadership in state government changes. So you may like the leadership today, but you may not like it tomorrow. And do you want tomorrow’s leadership who you don’t like having that ability to bully the professors who are speaking out, who are dissenting? We need dissenting voices in society and in our public institutions. We need people to be able to research things without fear of retribution.”

Joe Cohn, legislative and policy director for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), a nonprofit that works to protect free speech on college campuses, called HB 999 unconstitutional because it bans both majors and ideas that legislators have deemed disfavorable.

“There’s over 60 years of Supreme Court case law prohibiting government intrusion into higher ed,” Cohn said. “For example, there’s a case called Keyishian v. Board of Regents, and there, the Supreme Court said academic freedom is of a special concern of the First Amendment, which does not tolerate laws that cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom. And it’s hard to envision a law that casts more of a pall of orthodoxy than one that says, ‘These topics can’t be discussed, and these ideas can’t be discussed because the majority in the legislature don’t like those ideas.”

If HB 999 is enacted, both Cohn and Edwards said that their organizations plan to fight it. The ACLU of Florida is one of the groups, along with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and law firm Ballard Spahr, that filed a lawsuit to block enforcement of Florida’s Stop W.O.K.E. Act in public colleges and universities. FIRE took part in separate litigation against the legislation, which bans critical race theory (CRT) and allows legal action to be taken if CRT is taught. While in effect in K-12 schools, a preliminary injunction prevents the Stop W.O.K.E. Act’s enactment in higher education. Earlier this month, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied an appeal by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ administration to remove the injunction. As for HB 999 and its companion legislation in the Senate, Cohn said “if it does get into a courtroom, there’s very little chance that it will survive. The case law is very strong.”

For decades, FIRE has defended tenure because it has been one of the most important tools for protecting faculty with disfavored views, but the group has no position on what form tenure should take. It also acknowledges that tenure isn’t the only way to protect academic freedom, Cohn explained. The problem with the current crop of legislation, he added, is that it does not replace tenure with comparable policies that would allow faculty to speak freely and engage in scholarship and research without fear of reprisal.

Mulvey views any attack on tenure as an attack on academic freedom. She said legislation such as HB 999 amounts to censorship. In addition to that legislation, Texas and North Dakota have recently introduced bills that take aim at tenure. “We’re going down a dark road if we’re allowing the statehouses to censor what can be learned and what can be taught and what can be said in the classroom,” Mulvey said.

Over the past year, the University of Wyoming has withstood multiple attempts by lawmakers to defund its gender studies program, most recently in the form of a budget amendment in the Wyoming House that failed in February. A similar amendment was proposed unsuccessfully last year.

“We were really pleased that the Wyoming law that would have eliminated gender studies didn’t advance,” Cohn said. “It was a bad idea and it was important that the legislature recognized that and didn’t move it forward.”

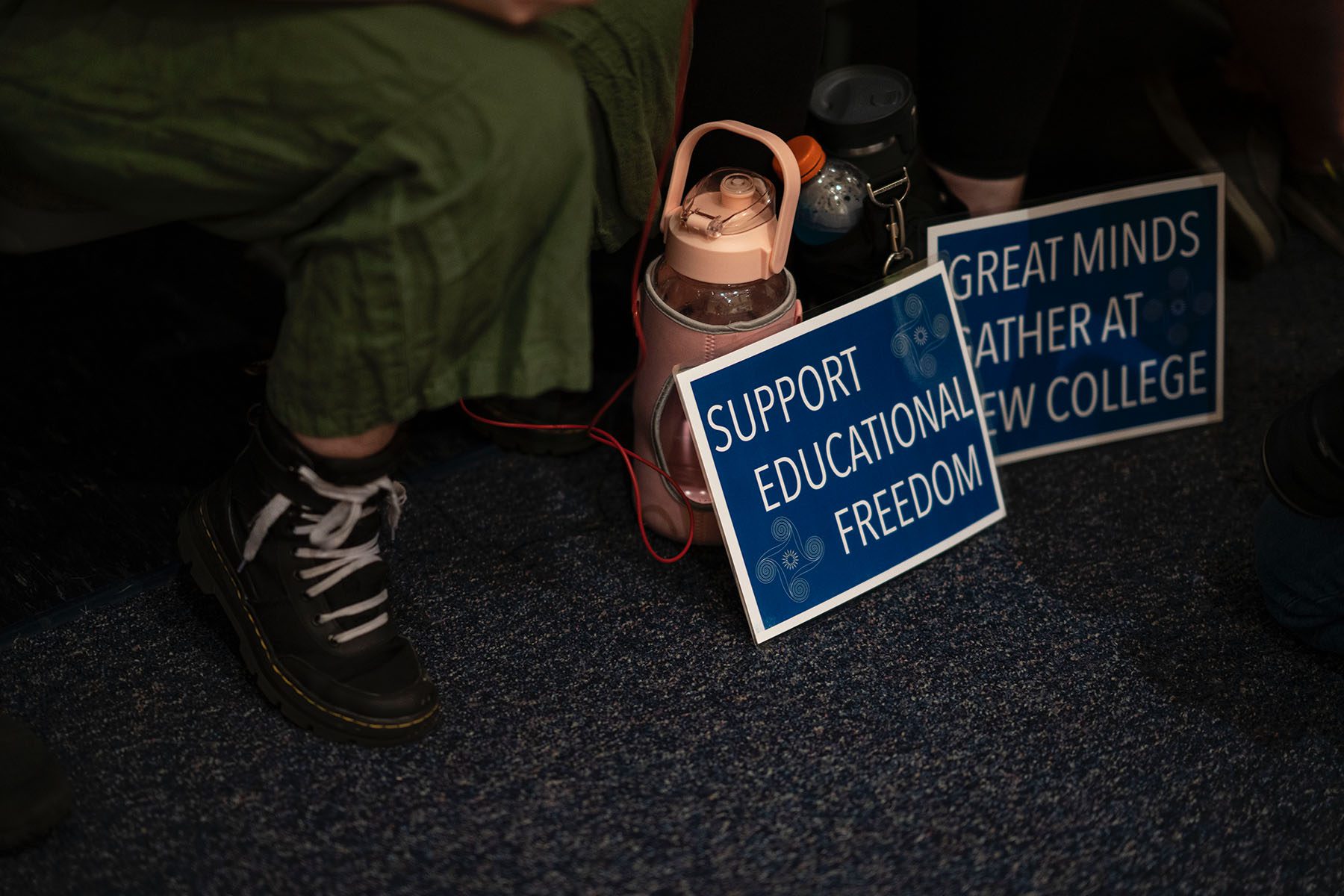

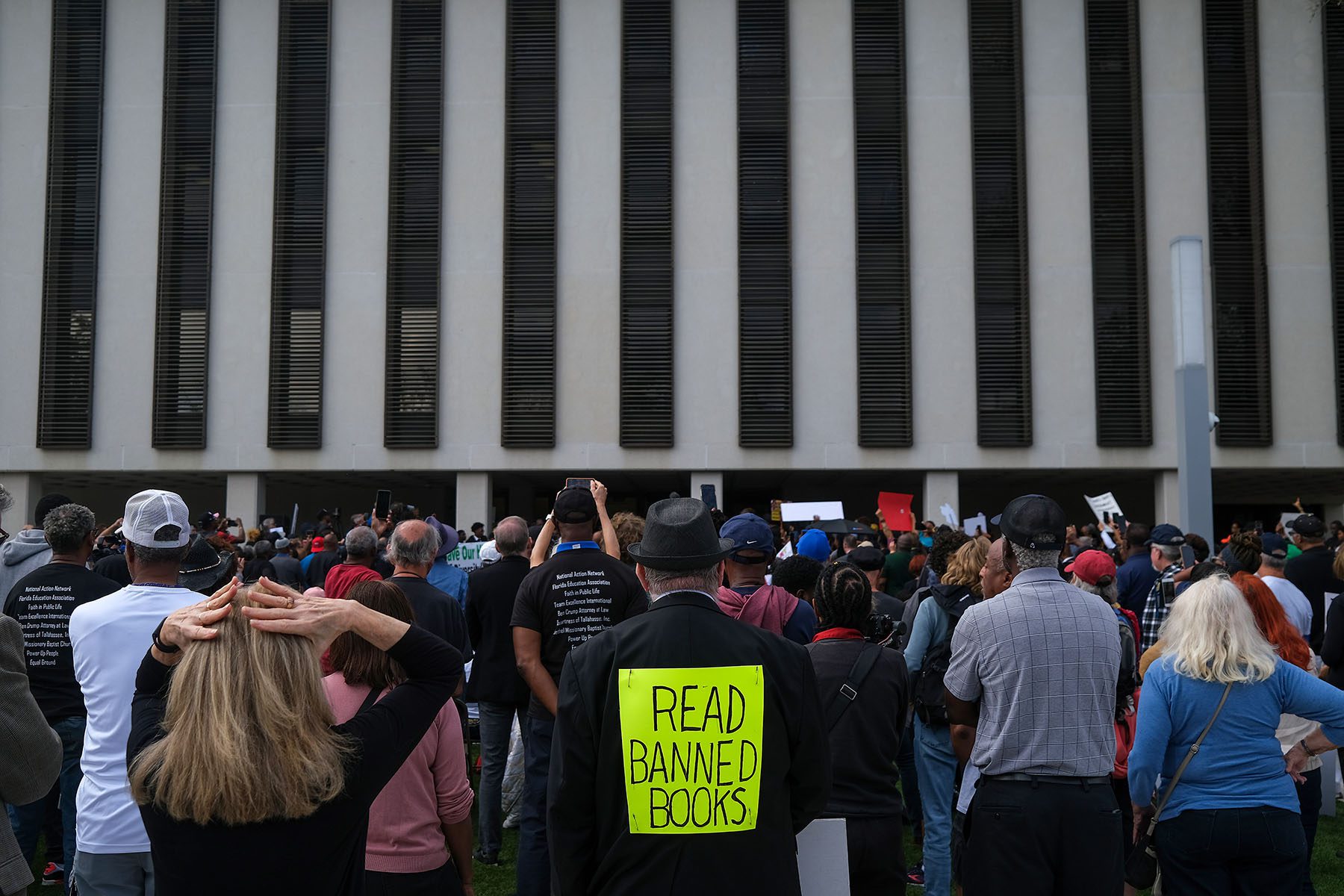

College students are also concerned about legislation that imposes restrictions on courses of study. Last week, Florida students rallied against HB 999 in the capital city of Tallahassee. Maxx Fenning, a senior at the University of Florida and the founder and president of LGBTQ+ advocacy group PRISM, also finds the legislation unsettling. He worries about HB 999’s potential impact both because PRISM is a proponent of LGBTQ+-inclusive education and because he is studying business administration with a specialization in education. As part of this specialization, he takes classes that focus on the role systemic oppression, gender identity, sexual orientation and gender theory play in education. It’s unclear if all classes focused on topics such as gender, race or intersectionality would be banned if HB 999 passes or if the legislation would simply prohibit students from majoring or minoring in these subjects.

“Being able to have access to this information is so impactful for young adults,” Fenning said. “Being able to have access to a wide diversity of opinions, a wide diversity of theories about the way that the world works, the way that we interact with each other, is part of building a nuanced view of the world.”

-

More education coverage

- Changes to AP African American Studies course set a ‘scary precedent,’ advocates say

- ‘Enough is enough’: L.A. school district workers demand historic raise during three-day strike

- Working parents and people of color — not ‘elites’ — stand to benefit from student loan forgiveness, advocates say

While studying education, Fenning said he’s learned about the importance of “mirrors and windows” — seeing oneself reflected back in the curriculum and being exposed to materials that help students empathize with people who are different from them.

“There’s so many ways that this sort of representation matters,” Fenning said. “So when we’re talking about things like HB 999, in particular, we see this effort to whittle down the worldview that we present into one that certain legislators agree with, to shatter those mirrors, to tint those windows and prevent us from being able to live and learn authentically.”

As both a graduate student and a lawmaker, Florida State Sen. Shevrin Jones is particularly concerned about HB 999’s potential impact on higher education in the state. The Democrat is pursuing a doctorate in higher ed administration at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Students go to school to explore diversity of thought,” Jones said. “We should not be in the business of interfering with that diversity of thought, interfering with that exploration. That is not our job. Our job is to create the best type of system where individuals can flourish, not push an agenda on students and on a system that’s been shown to work.”

Florida is home to four historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Although three of them are private, they receive state funding for certain academic programs. Jones questions how HB 999 could affect the state’s HBCUs and the nine Black sororities and fraternities known nationally as the Divine Nine. He wrote an MSNBC opinion piece earlier this month urging Black Greek-letter organizations to keep fighting the bill. He noted that language in the Senate version of HB 999 has been changed to offer some protections to Black sororities and fraternities, but he worries that the House bill still prohibits public colleges and universities from paying for “programs or campus activities that espouse diversity, equity, or inclusion or critical race theory rhetoric,” he said. Jones argues that this line could be interpreted in a way that would lead to the defunding of Florida’s Black Greek organizations.

Florida Rep. Alex Andrade, the Republican lawmaker behind HB 999, said that this was not his intent. “HB 999 in no way applies to student-led organizations,” he told The 19th in a statement. “Student organizations are neither contemplated nor affected by the bill.”

Jones said he knows the bill sponsors have said that’s not their intention. “But the problem is that, particularly in how the House bill is written, it could be implied because the bill clearly states that it prohibits state and federal fund usage for programs or campus activities that advocate for DEI and engage in political and social activism. Fraternities and sororities fall into that category.”

Edwards agrees that the broadness of the legislation may pose a risk to a wide range of campus organizations, including Black sororities and fraternities, Latinx groups, affinity groups or even veterans’ organizations.

“I’m sure they’ll say that they added language in the most recent version of the bill that permits expressive activity, to the extent it’s not inconsistent with regulations or university rules, but the problem there is that . . .after they passed the Stop W.O.K.E. Act, the Board of Governors then implemented regulation that was basically identical to what the statute prohibited. So if that happened [with HB 999], if they implemented a regulation, while the statute wouldn’t necessarily stop those things, the regulation would.”

It’s unclear what will happen to Black Greek-letter organizations if HB 999 is enacted, but Jones said that he eventually expects HBCUs to face questions about their right to exist, pointing out that they are already massively underfunded and that HBCU Tennessee State University is currently under scrutiny amid questions about mismanagement.

“The [TSU] president right now is having to defend the reason why the institution is important to the Tennessee state legislature,” Jones said. “And I think we will continue to see this questioning of whether or not HBCUs are still needed, which they are because HBCUs were founded because they were the only place where African Americans could be educated. Still to this day, HBCUs do admit students that PWIs [predominantly white institutions] just won’t admit.”

A potential consequence of statewide legislation that takes aim at diversity, equity and inclusion; prohibits students from learning about race, gender and sexuality; and weakens tenure is that faculty and students may decide to pursue scholarship elsewhere. Many progressive Florida youth with the means to leave the state plan to do so, Fenning said.

“It is not a good reputation to have as a state when your best and brightest cannot wait to get out of it and take their business elsewhere, quite literally their business and their economic impact elsewhere,” he added. “If there are greener pastures and they have the ability to get to those greener pastures, they’re gonna.”

Faculty are already telling their graduate students not to teach in states where there’s no academic freedom, Mulvey said, and some institutions in these states are seeing fewer donations.

Jones said that he has made similar points about HB 999.

“Many researchers, particularly in STEM, come here because they know they are secure in their work and they will be able to complete a research project without being tampered with, without anyone trying to come against their research,” he said. “They’re not going to even think twice about coming to Florida if they know that they can be fired for their views or fired for any reason if the board of trustees or the board of governors find a need to do so. No one’s going to come to teach in that type of state. I know I wouldn’t.”