“Do you have a dog?” “Who’s your boyfriend?” “Are you married?”

Anita Carson fielded questions from students about her personal life each year she taught for Polk County Public Schools in Florida, giving them a short presentation about her friends and family and asking them to do the same. But for the first time in 12 years, when school resumes this fall, the bisexual middle school instructor won’t be in a classroom. She resigned in May due to a combination of factors, chief among them Florida’s recent passage of laws, including “Don’t Say Gay” and the Stop WOKE Act, that limit what educators can say about issues such as sexual orientation, gender identity and race.

The laws prevent educators, especially members of the LGBTQ+ community, from being authentic about their lives, covering important subject matter and meeting the socioemotional needs of students, Carson contends.

“With the very blatant attacks on education and on marginalized communities, I just couldn’t teach anymore,” said Carson, who is now a community organizer for Equality Florida, an LGBTQ+ advocacy group. “I cannot fathom being in a classroom where I cannot support my kids to the fullest of my ability because there are now laws that tell me what I can and cannot do to support my kids; like, that’s heartbreaking.”

Nationally, teachers have resigned in droves during the pandemic. A National Education Association poll released in February found that 55 percent of teachers plan to exit the profession sooner than planned, up from 37 percent last August. Shortages are difficult to track or compare nationally because states, counties and cities may use different methodology to determine their needs, including current openings, teacher polls and information about the number of students getting education degrees.

Florida has more than 9,000 school personnel openings, and roughly half are teacher positions, according to the Florida Education Association. In Virginia, there are as many as 2,500 teaching vacancies. In Illinois, there are over 2,000 such vacancies, and Georgia projects that it will need up to 8,000 teachers over the next few years.

Teacher shortages disproportionately affect students of color, who are overrepresented in under-resourced schools where staffing issues are often more severe and leave students with instructors who are likely to be inexperienced and underqualified.

While teacher shortages have left no region of the country untouched, Florida is a flashpoint because the state’s education policies, political climate and anti-teacher rhetoric contribute to the crisis.

In Florida, about “450,000 kids started school last year without a permanent teacher,” said Norín Dollard, senior policy analyst and KIDS COUNT director at the Florida Policy Institute. “Of course, it’s going to have an effect on academic success.”

A unique set of challenges is causing Florida educators to call it quits. In addition to passing laws that critics say target the LGBTQ+ community and people of color, political figures in the state have characterized educators as threats to students and parents. Tired of what they consider to be character assassination, low pay and a lack of job security, teachers in the Sunshine State are resigning in worrisome numbers. In 2010, for example, Florida had just 1,000 teacher openings, according to the Florida Education Association. Today, the organization warns there aren’t enough aspiring educators to fill openings that are at least four times as high. The Florida Department of Education did not specify how many teacher vacancies the state has but disputed that the figure is as high as the teachers’ union reports.

Not only are an increasing number of people leaving the profession, a decreasing number of people are entering it. In 2010, there were about 8,000 students who graduated from Florida’s colleges and universities with education degrees, said Andrew Spar, president of the Florida Education Association. This year, the association expects between 2,000 and 3,000 students to earn degrees in the field.

“First and foremost, it’s just bad policies that have been passed in Florida that have had a huge impact on people deciding not to come into the profession and people leaving the profession who otherwise intended to stay,” Spar said. “The only thing the pandemic did was accelerate how quickly people left the profession.”

Just a couple of years ago, quitting education had not crossed Carson’s mind. In 2020, she felt passionate enough about the profession to run for a seat on the Polk County Public Schools board. Although she lost the race, she managed to navigate virtual instruction during the first year of the COVID-19 crisis, a period that she and her colleagues found extremely stressful. Still, she appreciated the lawmakers in her state for thanking educators and other essential workers for their contributions during the pandemic. Then the rhetoric took a sharp turn. Political groups began portraying teachers as nefarious influences in students’ lives.

“These right-wing extremist groups were talking about teachers indoctrinating kids with liberal [agendas] and saying that teachers are groomers and pedophiles if they ever support LGBTQ-anything in the presence of a minor,” Carson said. “I couldn’t take it anymore. I was like, ‘I have to get out of this. This is toxic. This is not the space that I want to be in anymore.’”

The Sunshine State is the epicenter of Moms for Liberty, a conservative parent group co-founded by two former Florida school board members. Their movement for more parental oversight of curricula related to race, gender, sexuality or politics spread across the nation during the pandemic. The group holds such sway in conservative circles that Betsy DeVos spoke at its summit Saturday, garnering headlines for reportedly calling for an end to the Department of Education, the federal agency she led during former President Donald Trump’s administration.

The so-called parents’ rights movement has led to the introduction of book bans, critical race theory bans and curriculum transparency bills in most states. Florida, however, has gone a step farther with the passage of “Don’t Say Gay” and the Stop WOKE Act. While the former prohibits educators from teaching lessons on sexual orientation or gender identity to children in grades K-3 — which Spar denies ever happened — the latter would allow parents to sue if they suspect that children are learning about critical race theory in class. In addition, last year Florida passed a “Parents’ Bill of Rights” law that prohibits government entities from infringing “upon the fundamental rights of a parent to direct the upbringing, education, health care and mental health of a minor child” without justification.

Carson said this sort of legislation can lead to LGBTQ+ and other teachers from marginalized groups hiding themselves from students. Straight teachers, she added, will likely feel more comfortable answering questions from students about their personal lives than LGBTQ+ teachers will. Laws such as “Don’t Say Gay” also lead to confusion because neither teachers nor school districts know exactly how to interpret them, Carson said.

“It was very purposely vague, so that they could continue pushing the concept that it’s not discriminatory,” Carson said, noting that SB 1557 does not actually include the word “gay.” “It doesn’t make it any less discriminatory because everyone knows what they were trying to accomplish, but it does make it a lot harder to implement and makes the job of educators 10 times more frustrating because the districts that we teach in…are trying to avoid lawsuits. So they’re either ignoring it entirely and giving no one guidance, or they are giving incredibly conservative guidance to try and stay away from lawsuits.”

Although Carson taught science, she said the Stop WOKE Act caused her to question what she would be able to teach. She was uncertain if she could discuss current events with students, which they routinely bring up, even if she presented the topic in a way that was historically accurate and left out her personal politics. Plus, Carson said that she made a point in her classes to highlight the achievements of underrepresented scientists, such as the late Kenyan environmentalist Wangari Maathai. In 2004, Maathai became the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. The Stop WOKE Act indicates that she should not mention Maathai’s race, gender or country of origin, Carson said, even though the information could potentially inspire students.

Spar said laws such as the Stop WOKE Act and “Don’t Day Gay” hurt educators. “Teachers are caring individuals who always want to do the right thing, and it’s very hurtful and very frustrating when you’re trying to do the job you’re hired to do and there’s constant regulation preventing you from doing that,” he said. “And then you have a governor going around the state saying things like, ‘Teachers are teaching kids to be gay, or teachers are teaching sex education in grades K-3. Teachers are teaching kids to hate White people, or teachers are teaching kids to hate cops,’ all of which is not true at all. It weighs on the profession.”

The controversial legislation Florida has passed over the past year may lower teacher morale, but it is not the only factor causing educators to leave the profession. Spar said that the state’s policies on teacher pay and job security have contributed to the educator shortage. In March, Governor Ron DeSantis set aside $800 million in Florida’s budget to raise minimum teacher pay and increase veteran teacher salaries, the third consecutive pay hike he’s approved for teachers. But Florida ranks 48th nationally in teacher pay, with an average salary of $51,009 during the 2020-21 school year, according to the National Education Association. Also, recent salary increases there have largely benefitted newcomers to the profession, while veteran teachers lag behind their counterparts elsewhere in pay. Spar attributes this problem to Florida’s Senate Bill 736, which passed in 2011 and changed teacher pay, evaluations and job security.

“The longer you’re teaching, the smaller your pay increases,” Spar said of the legislative change. “A teacher with 10, 15, 20, 30 years of experience today is making less money in Florida than what teachers with that exact same experience made 10 or 15 years ago. I had a teacher contact me. She has been teaching for 25 years, and she’s making $52,000 a year. She found a salary schedule from the 2008-2009 school year in her district, and a teacher with 25 years experience back then was making $59,000 — $7,000 more than she is today.”

Spar said that Florida teachers also no longer have tenure, so they don’t know until the end of each school year if they’ll be invited back for the following year. Teachers who live geographically close enough to earn more pay as educators in the neighboring states of Georgia and Alabama are abandoning Florida schools to do so, said Dollard, of the Florida Policy Institute.

By raising salaries, providing more job security and reversing laws that keep teachers from doing their best work, the state may be able to retain and attract the educators it needs, advocates say.

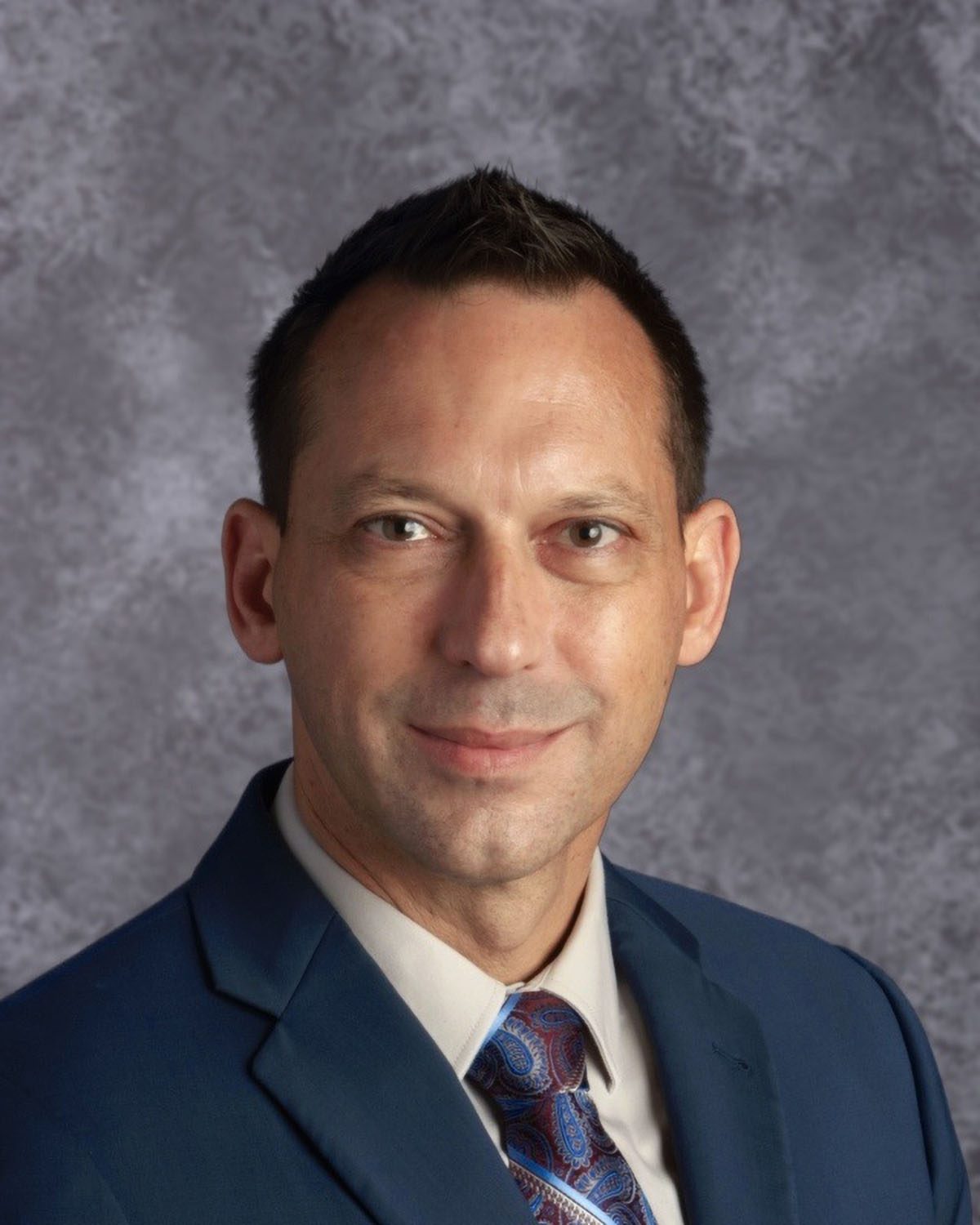

Adam Lane, principal of Haines City High School in Polk County, Florida, has come up with some creative solutions to ensure that his school has the personnel it needs. A few years after he became principal in 2015, he began recruiting alums to join the staff. Today, nearly a quarter of his 247-member team are graduates of Haines City High, which has a student body of about 3,000.

“When seniors graduate, I work with them to be substitutes,” said Lane, who was named the 2022 Florida Principal of the Year by the National Association of Secondary School Principals. “Not only are they making money, they are getting experience as a teacher. In four years, they’re ready to go and they have a job waiting for them back at my school working with me.”

Lane enjoys bringing on former students as teachers because they already know the school’s mission, vision, procedures and staff. The newcomers also appreciate a starting salary of about $48,000, but Lane acknowledged that mid-career teachers likely need financial incentives to keep them in the profession.

As Lane ensures that his school has a pipeline of teachers, he is also making a concerted effort to foster relationships with parents during a time when the two groups are being positioned as opponents in the political sphere. With the help of the school guidance counselor, Haines City High launched an initiative called Parent University that connects parents to teachers, counselors, administrators and social workers at the school so they can see firsthand what the jobs entail.

“There’s a lot of parents out there that want to be better parents, and they want to understand the educational process more, but how are they going to do it if they don’t have an invitation to come to a school?” he said. “The more parents you educate, the less friction or misguided information you’re gonna have.”

As an organizer for Equality Florida, Carson is now educating people about Florida’s education policies and their potential ramifications. When she heard about the job on Facebook, she knew it was the right fit.

“I was like, ‘That’s it. That’s what I need to do. That just fits really well as an LGBTQ educator and an advocate for kids,’” she said. “I am…organizing around these crazy moments that are happening in Florida in schools all across the state. Whether it’s [‘Don’t Say Gay’] or the Stop WOKE law, they’re having to come to terms with these laws without a whole lot of guidance…and with the knowledge that these laws are meant to be discriminatory.”