This Black History Month, we’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

Black History Month has been reserved to acknowledge and commemorate the achievements of our ancestors, their great contributions and what they’ve done for the world. Growing up we learn about the likes of Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman and W.E.B. Du Bois. We’re reminded of our history, where we came from and the freedom fighting that took place to give us the platform to share our stories.

While this history isn’t that far removed, it’s important to remember that Black history continues to be made around us and is within reach.

Several Black staffers at The 19th have come together to reflect on what this month means to us: It’s about family, teaching ourselves Black history when educational systems fail us, and embracing the unique gifts and individuality our ancestors fought for us to have.

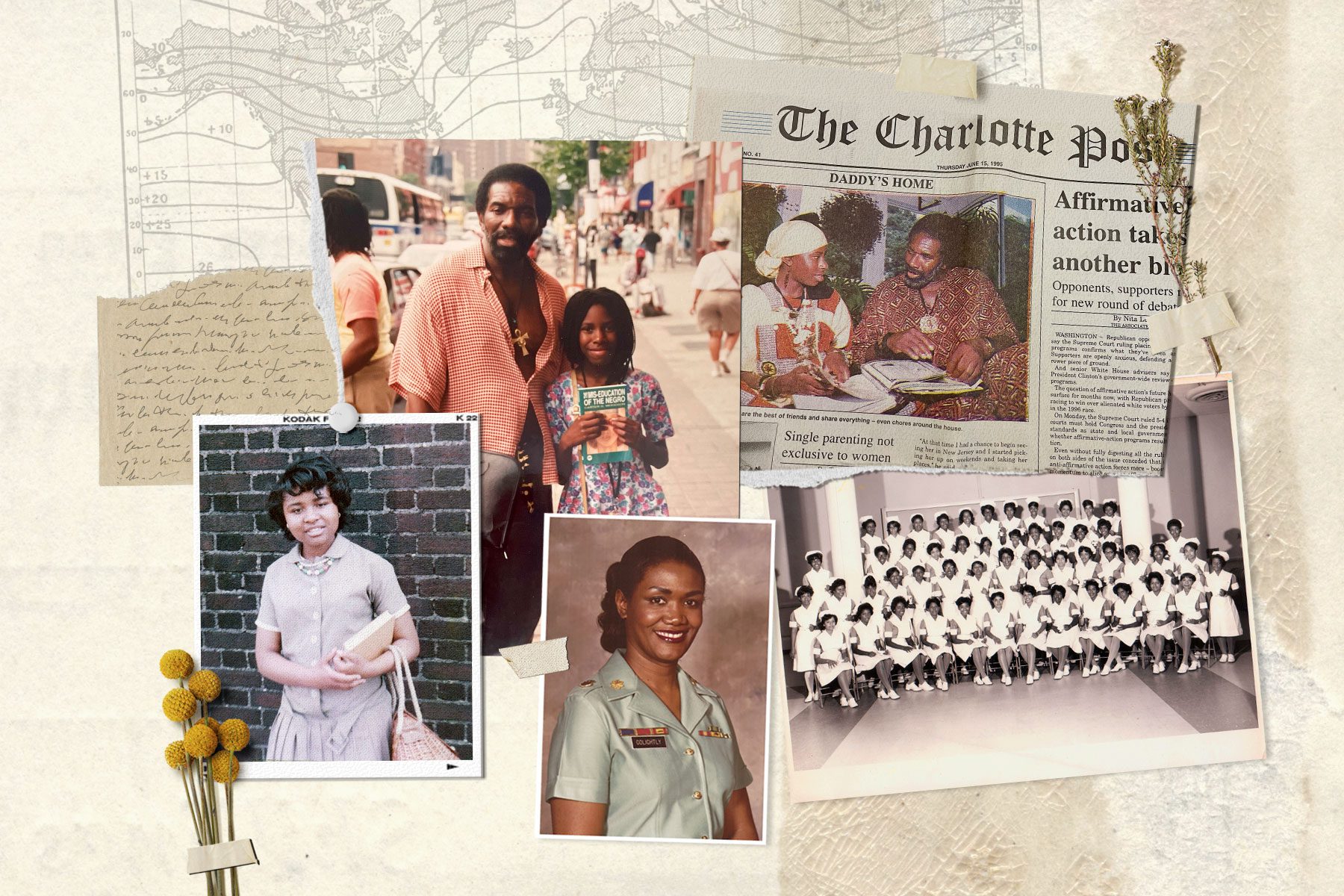

‘Black history is my father’

Black history is my father, Ronald Conroy.

Growing up, he was exposed to negative stereotypes about Black people despite the priceless contributions we made to America. As my Dad acquired knowledge of the African diaspora, he taught me. We attended African history lectures, were activists and read books like “The Miseducation of the Negro,” because, “it’s your history, Miss.” My Dad encouraged me to become Princess Zurii, professional Griot. I eventually realized that I received gifts that many did not get until college, if that. My father’s teachings are why I have pride in my African name and my cultural birthright. It is because of him that I know my “why” — even on my worst day, even when I forget. He is why I know Black history is American and world history.

Once a living embodiment of Black history, Ron Conroy is now the ancestral legacy of it. Ase. — Zurii Conroy, people operations manager

Celebrating Black history for me is looking back at the impact pioneers and leaders have had on our community. It’s also recognizing that many of these pioneers are members of our own families.

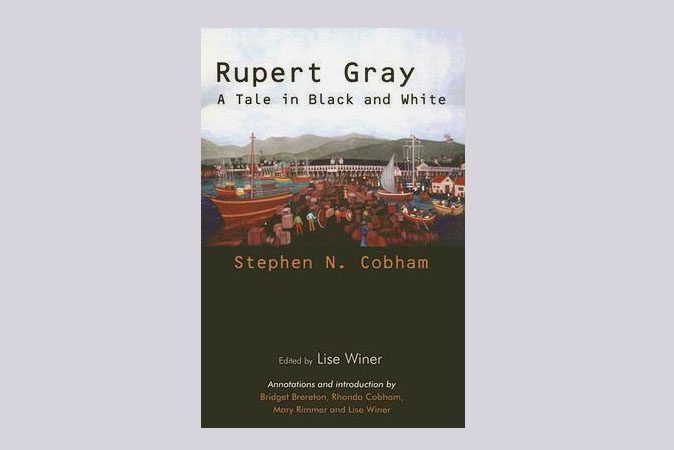

For me, Black History Month is a chance to reflect on the contributions my family has made to allow me the freedoms I have today. My mother was a pioneer in so many respects. She was and continues to be my hero and measure of excellence. Clarice Golightly-Jenkins, Ph.D., MSN, CNS, made reimagining a transformed health care system — providing emerging, new and robust, equally accessible standardized health and wellness across the life spans of all populations — her charge.

While there are many things that remind me of my mother’s legacy, there are few that match the image of her nursing class photo. In 1966, she stood bravely, along with 50 of her peers, forging ahead with the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) story. It’s impossible to find a nursing class of all Black women today. My mother always described this day as a special one that both of my grandparents traveled to witness. Tuskegee was an extension of her home and community upbringing — as it was for many Black students. This was a historic day that remains top of mind for me, every day. — Clarice Bajkowski, creative director

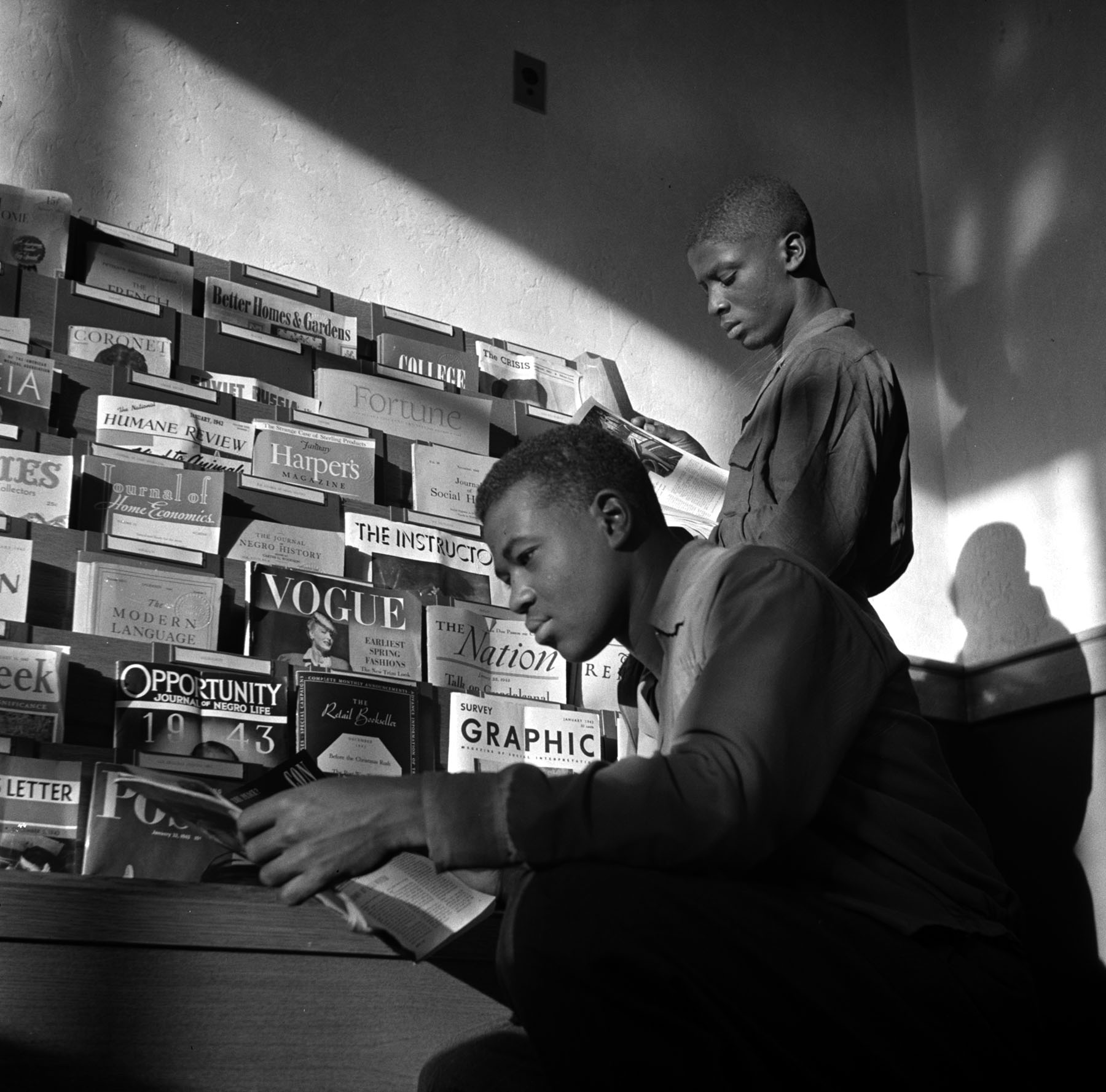

When my mother was 13 years old, she was sent to live with relatives in Chicago because she’d become too mouthy for Sheffield, Alabama.

It was 1959, and she’d challenged the public library’s restrictions for her as a Black child in a small Southern town: a White person had to sign her library card, she could only check out one book at a time, and when she returned the book, each page was examined before she could have another one.

I’ve known this story for as long as I can remember, and even now, my mother trickles out new details.

For me, Black History Month has always been about tapping into my personal birthright of rebellion and never forgetting where I came from. I was born to disobey, raised by someone who speaks out about injustice no matter the cost. And whose love of learning — and reading — inspires me every day. — Karen Hawkins, story editor

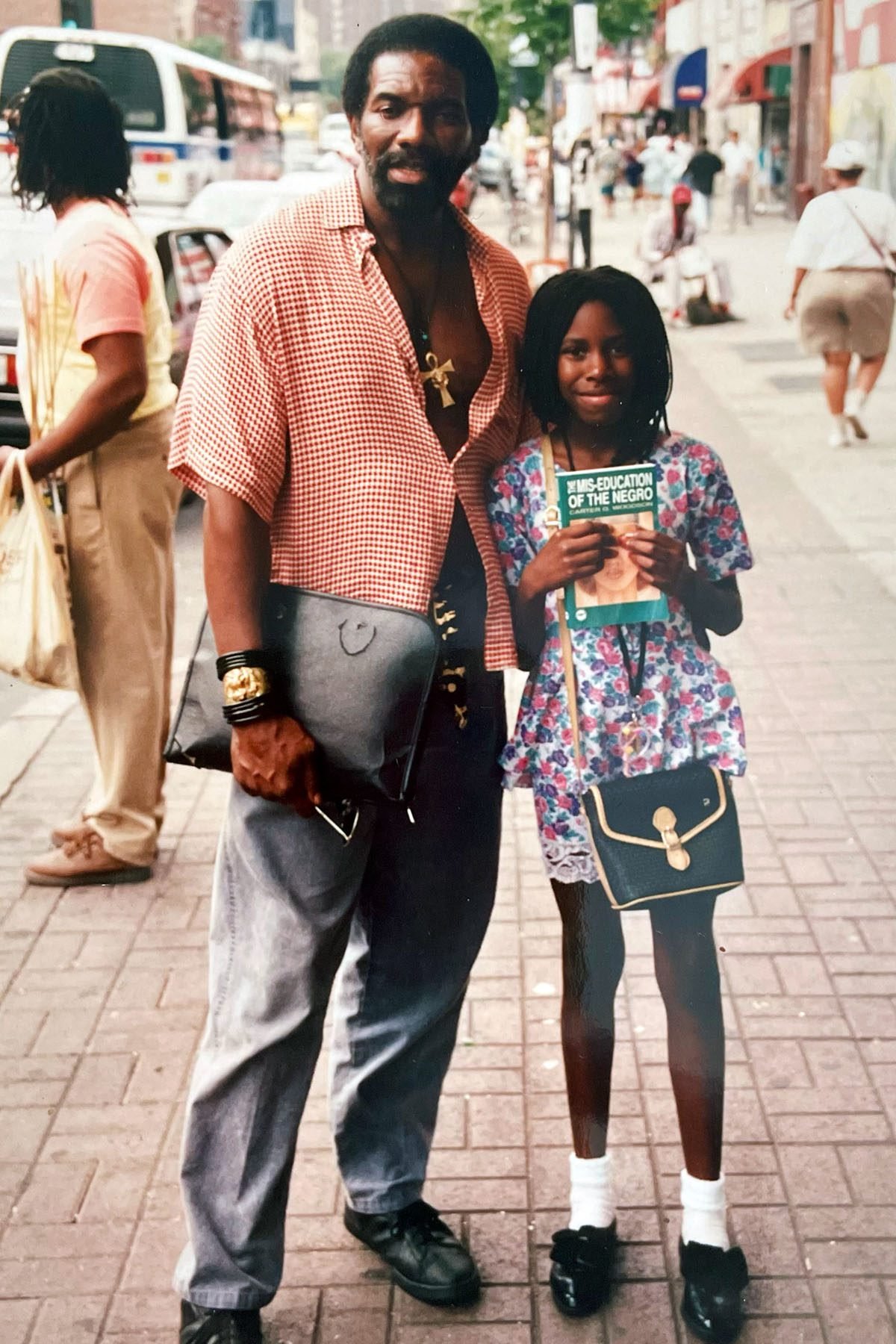

I was well into my 20s — and my writing career — when I first learned where the gift came from.

Rambling calls with my father in Trinidad were usually funded by $10 international calling cards from the corner gas station. This time, he called me. “Grab a pen and write this down,” he said perfunctorily.

What I got was a piece of new-to-me history: Stephen N. Cobham was my great-grandfather, and in 1908, he published “Rupert Gray,” a novel tracing an interracial love affair.

Black history reflections — and the path forward

This story is part of our Black History Month coverage. From in-depth Q&As to staff reflections and our inaugural 19th Celebrates event, we’re focused on telling stories along the twin themes of Black joy and Black resistance. Explore our work.

He was a poet and teacher-turned-law-clerk who was dedicated to the upliftment of Pan-Africanism. He opposed British rule and advocated for self-government. He left the family for Guyana and never returned.

This month, I think about the complicated legacies of Black men, about how the history of Black folks in the Caribbean and United States are intricately woven, from Claudia Jones to Stokely Carmichael. And about my responsibility every time I pick up a pen. – Kari Cobham, fellowships director

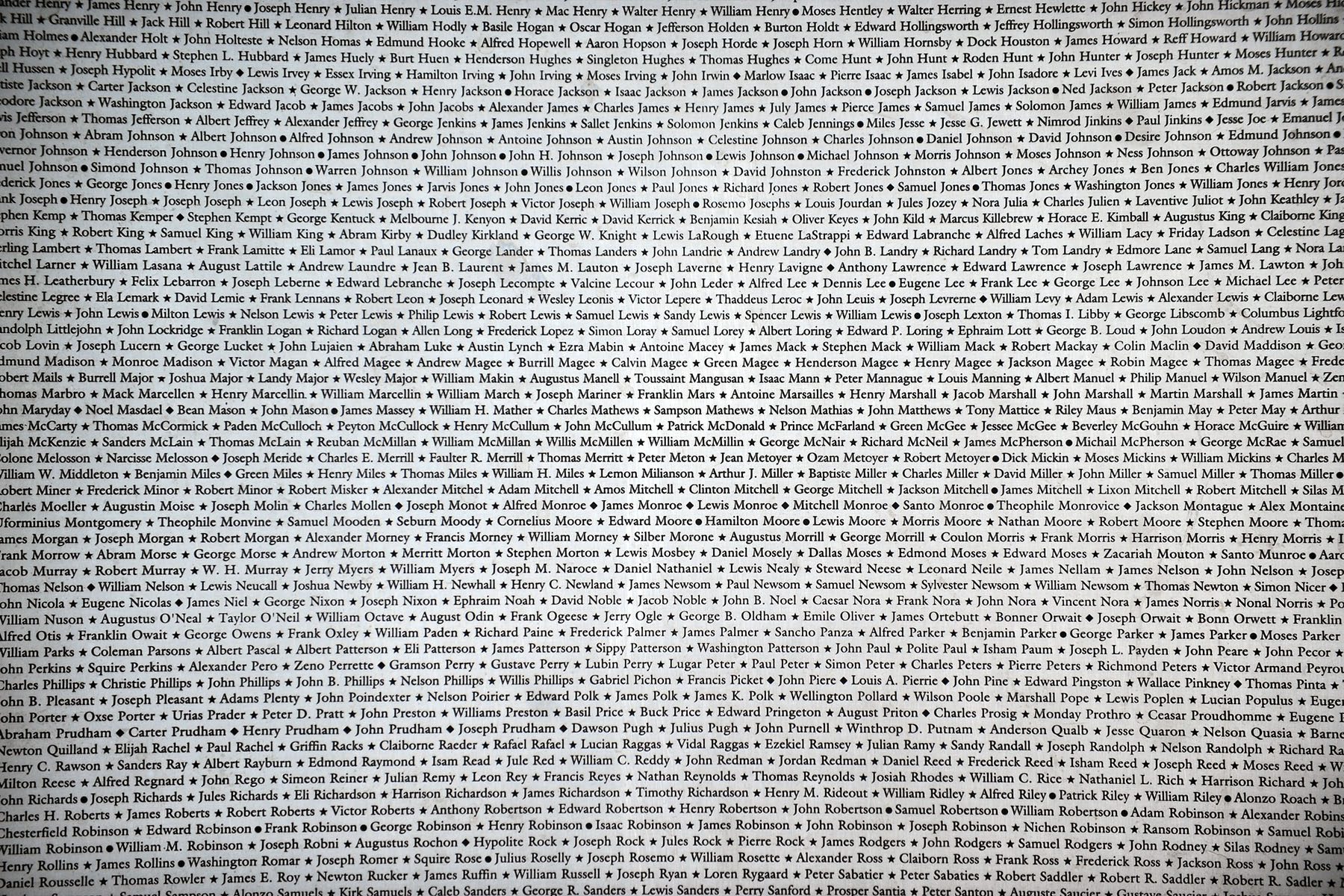

A decade ago, my dad and I began researching our family’s roots. What we’ve found has deeply personalized my understanding of Black History Month.

As we celebrate with the Association for the Study of African American Life and History’s theme of Black Resistance, I am reminded of my fourth-great-grandfather, Augustus Rochon. In 1863, he enlisted in the 20th Corps d’Afrique Infantry at Fort Pike, Louisiana, joining thousands of Black soldiers who fought to liberate our people from slavery. Nearly 160 years later, we traced our fingers over his name at the African American Civil War Memorial, just blocks from where I was studying at Howard University.

I am also reminded of my family members who were domestic workers, fishermen, musicians, bricklayers and those whose job was survival. Because they survived, I exist.

This month is a celebration of my freedom fighters. It reminds me of the progress they made and charges me to continue for future generations. — Daja E. Henry, editorial fellow

‘Keeping Black history alive’

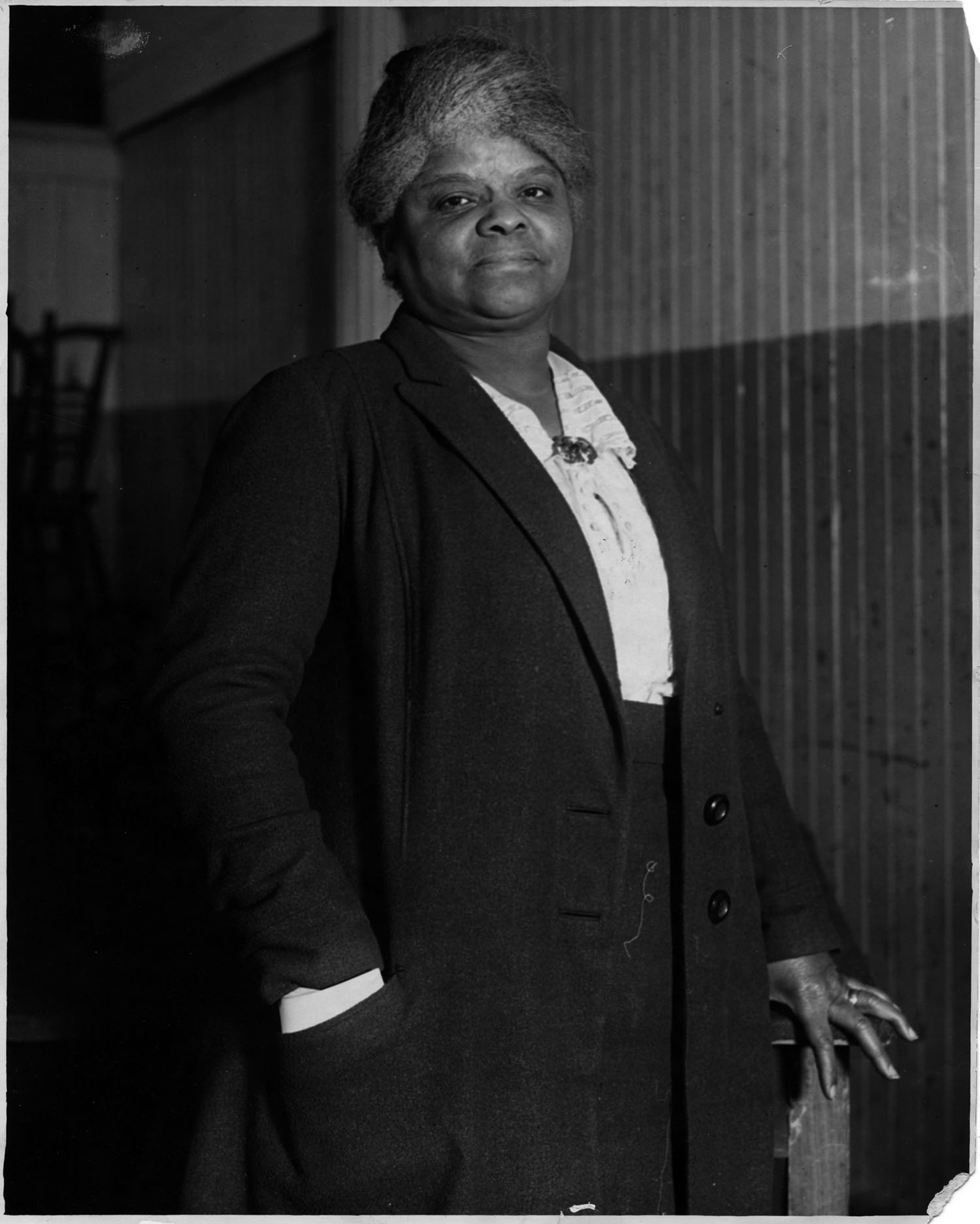

When I was a little girl, my parents gave me a book of prominent Black Americans. They told me to choose one and write a short biography. Reading this book is how I learned about Ida B. Wells and eventually found myself on the path to being a journalist. As a young Black girl, I wanted to learn more about Black history throughout the year. I understand that might not be everyone’s experience. That’s why I appreciate Black History Month. It gives everyone an opportunity to reflect and learn more, especially those who might not ordinarily take a deep dive into Black history. If we are intentional about doing this, we will be surprised about what we learn. Maybe, just maybe, learning about Black history will give people a better appreciation of Black people who are living today. — Rebekah Barber, editorial fellow

Though Black History Month starts on February 1, in my childhood home it began a couple of weeks earlier on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Every year my siblings and I, guided by my mother, would bake a cake to celebrate the civil rights leader’s birthday on January 15.

Our MLK celebration each year kicked off a series of museum visits, film viewings, bedtime readings and special events dedicated to sharing the reality of the Black experience in the United States. I did not appreciate the reason behind my mother’s efforts nearly enough at the time. As an educator and a scholar of the racial-political dynamics of the American education system, my mother knew both the importance of keeping Black history alive, as well as the ways our White-dominated society rewrites the country’s narrative.

That reframing continues to this day. States around the country are looking to restrict or ban certain teachings about race and systemic oppression. I am grateful that today we have more platforms and opportunities outside of U.S. schools to tell our own history and stories. — Candice Norwood, reporter

Black history is under attack. Over the past few years, most states in this country have introduced legislation to prohibit the teaching of critical race theory in K-12 schools. Since grade schools never taught CRT in the first place, these laws have simply silenced educators from teaching lessons about race. Books about Black history makers such as Wilma Rudolph, Ruby Bridges, Rosa Parks, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and former First Lady Michelle Obama have faced censorship. Many teachers fear that if they comment at all about our nation’s racial history they will be fired, sued or otherwise penalized. This is a disservice to educators and to young people.

Knowing the truth about the past helps us to better understand the present and imagine a different future. And the reality is that Black history involves far more than trauma. As a writer, I am inspired by historical Black creatives, including the poet Phillis Wheatley, landscape painter Robert S. Duncanson, dressmaker Elizabeth Keckley and sculptor Edmonia Lewis. Students deserve the chance to learn about these figures and many more who have embodied Black genius. — Nadra Nittle, education reporter

‘We’re not a monolith’

Black History Month and the idea of Black excellence, to me, is really about allowing everyone across our lived experiences to celebrate the people and things they love the most. That Black person who innovated in video games? Shout ’em out. You joined a Black bicyclists group? Awesome, and kudos to the person who started it.

We’re not a monolith, and our celebration and commemoration shouldn’t be either. No matter our gender or sexual identity, age or interests, this month should be a time to laugh, cry, learn, sing, dance, shout or maybe just a time to rest and reflect. Less gatekeeping and stern speeches and more inclusivity. Life is already hard enough, and has been for our people for generations — I hope this month allows folks to do what feels right. — Lance Dixon, audience engagement producer

Black History Month, to me, means embracing my whole self in a world that teaches our culture in bits and pieces. As a child, my mother gave me books about the innovators and game changers who made it possible for me to be an individual with the privilege of choice and self-expression. Black history to me means home. I understand that home is not a tangible place but a feeling. A feeling of being seen, heard, felt as a human being and nothing less. It is impossible to embrace your whole self if you feel your existence is not valid. Reading and learning about my history validates every aspect of myself from my hair to my creative expression. — Jamila Wood, product fellow