We’re making sense of the midterms. Subscribe to our daily newsletter for election context and analysis.

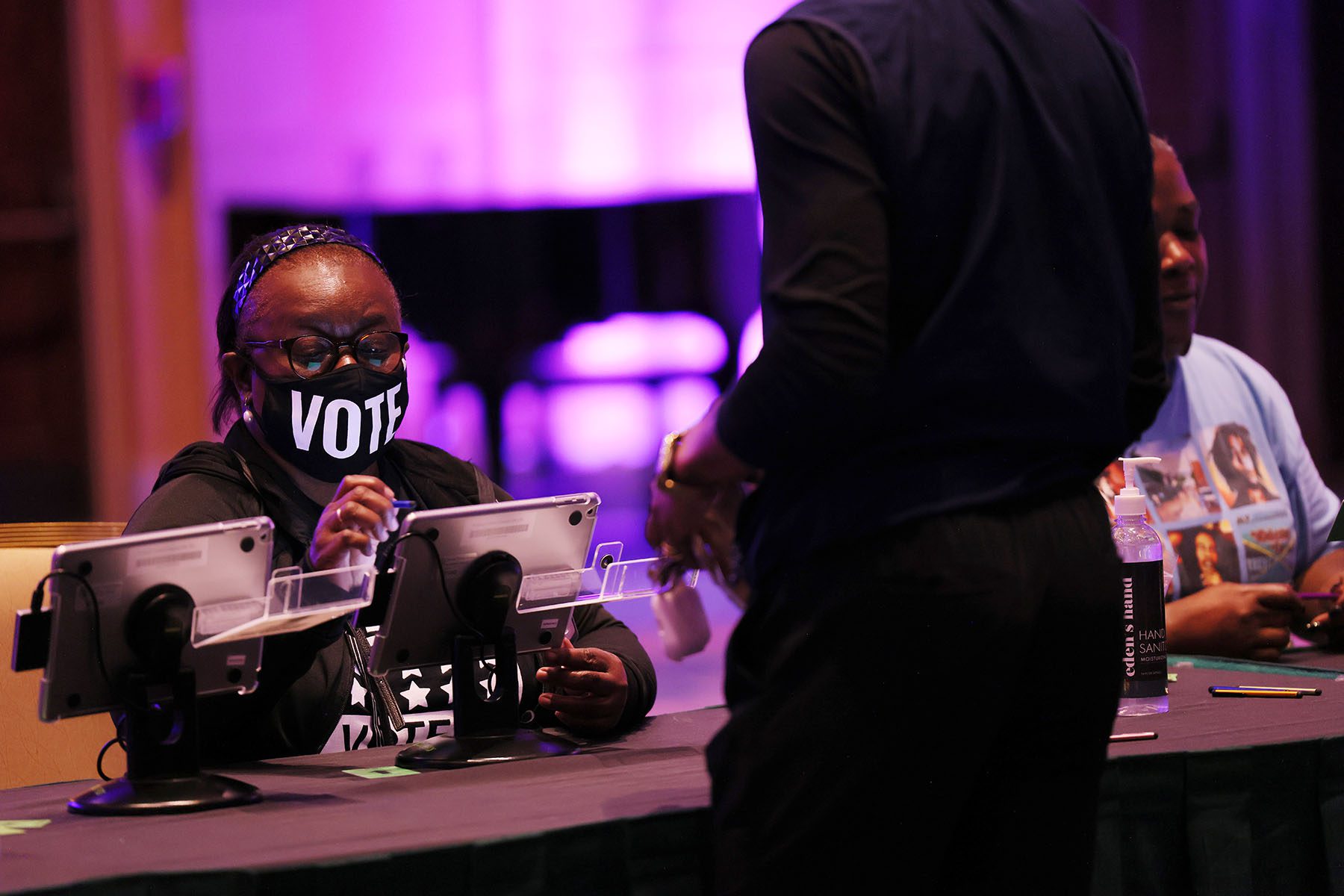

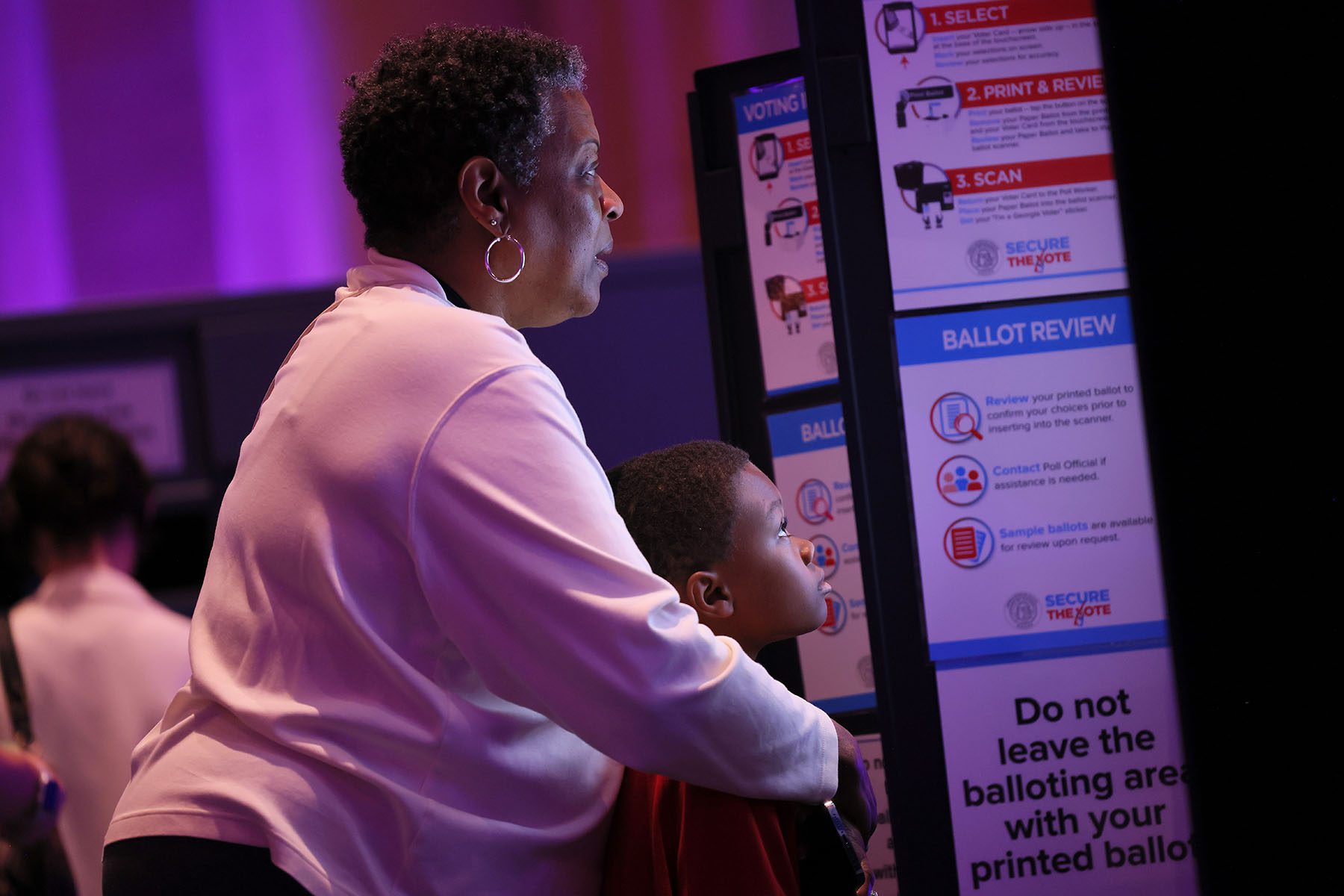

MARIETTA, Georgia — With the distrust in elections stirred up by false conspiracy theories not yet settled from 2020, election workers — a predominantly woman-led workforce — headed to their local polling locations across the country on Election Day. They are literal stand-ins for democracy — holding onto the belief that voting can be executed not only easily, but joyfully.

With more than 45 million votes cast in the midterm elections in several weeks of early voting — and records set in states including the swing state of Georgia — enthusiasm is high as voters seem determined to have their voices heard on issues such as abortion, gun violence and the economy.

Isolated problems have popped up in some battleground states, with reports of voter intimidation and legal challenges to ballots cast. These instances remain outliers so far.

The one-off problems are playing out in the wake of two years of upheaval: Some longtime election administration officials left their positions amid harassment and threats of violence following the 2020 election. Others, though, committed to staying and making sure people cast their ballots. Their numbers are augmented now by poll workers, who join the ranks temporarily in the weeks leading up to Election Day — and their optimism about their role in restoring faith in elections in their own communities.

Carla Butcher certainly feels hopeful. She set her alarm for 4:45 a.m. on Tuesday to give herself enough time to get to her polling place where she has worked for 17 years— currently as an assistant manager. She brought pumpkin mini muffins for her fellow workers, who met her at 6 a.m. at the precinct, housed in the gym of a Catholic Church in eastern Cobb County, just outside Atlanta. She expects at least a 15-hour work day.

A few hours into her shift, she was lively as voters checked in, greeting them by name and asking one person how someone’s mother is feeling, another about their new grandchild.

“I like feeling that I’m giving back, and helping,” the 71-year-old told The 19th. “I’m a big believer in, if you’re not willing to help in some way, then you’re not doing your job in life.”

Across the street from this precinct, political divisions are on full display. A sign reading “Had Enough? Vote Republican” stands just a foot away from one that says “Regulate Guns Not Women.” The races in this state could determine control of the U.S. Senate and whether America elects a Black woman as governor for the first time, and the populous suburban Cobb County is often a bellwether in the purple state.

Election administrators, poll workers and voting experts told The 19th that they’re going into Election Day with some trepidation about the ongoing dynamics. But they also expressed hope that the existing guardrails that ensure the country’s election system are safe and secure will continue to hold.

“I do, perhaps, have a touch of anxiety. … I will say this is the first time — in probably what, 20, 25 elections? — that I’ve had any anxiety, just because of what’s going on these days,” Butcher said.

But she added: “We have a very well-run system … the integrity of the elections we have is to the very best of anyone’s ability.”

Ellen Levine, 68, a longtime Cobb County resident and former poll worker, said she stopped working the polls during the pandemic and hasn’t returned because she doesn’t “feel comfortable” amid the rising political tension in her community.

“Watching the abuse the poll workers took with the election denying and the possible presence of poll watchers that have a really devious agenda coming in — it makes me nervous. You read about armed people coming into the polls,” she said. “I’m not so much afraid of there being a shooting, but I am afraid of intimidation tactics.”

Aunna Dennis, executive director of Common Cause Georgia, a nonpartisan voting rights group, said the Big Lie spread by former President Donald Trump and his allies is unfairly impacting how people perceive the security of elections. She said election officials need more guidance and resources.

“Right now what we have is a system that is reacting to a problem that doesn’t exist, the Big Lie,” she said. “People are saying elections are fraudulent, that they’re not done with integrity — but we know this is not true.”

Dennis said despite these realities: “There is enthusiasm and there is energy that democracy will still move forward in Georgia. Despite the hurdles that we may face and the things coming at us from folks who want to really impede on democracy and people being able to cast their ballot, people are voting.”

Over the weekend, officials in Cobb County acknowledged that more than 1,000 absentee ballots that were requested in October were never mailed out. Janine Eveler, director of elections and registration for Cobb County, said in written communication with officials that there had been staff turnover and new people learning procedures. She wrote: “Many of the absentee staff have been averaging 80 or more hours per week and they are exhausted. Still, that is no excuse for such a critical error.”

Following a last-minute lawsuit by the ACLU of Georgia and others on behalf of impacted voters, a judge Monday ordered the county to give those people more time to submit their ballots. Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican who is up for reelection and who was a key figure in pushing back on Trump’s Big Lie messaging in 2020, called the incident isolated.

Sara Tindall Ghazal is a member of the State Elections Board in Georgia, which works with county elections boards throughout the state. She was appointed by the Democratic Party, but Tindall Ghazal described her work on the board as focused on general elections administration.

Tindall Ghazal noted that a 2021 state law shortened the window for voters to request and return an absentee ballot.

“Cobb County has traditionally been one of the better run counties in terms of election administration,” she said. “But everyone is under pressure at this point.”

Rachel Orey, associate director of elections for the Bipartisan Policy Center think tank, said people need to understand that election administration has always included human error — there’s just more attention to it at a time of heightened tension. They said if headlines emerge about ballots and human error, people should recognize that there are also systems in motion to address them.

“The job of an election administrator is getting more and more challenging. They’re expected to do more: to be communications experts, security experts and still run an election,” they said. “And without an increase in resources to those election offices — to hire more support staff, to do more training — of course there are going to be mistakes.”

Orey said people need to practice patience and caution Tuesday and in the days ahead. People should expect election results for some races to take time as administrators process ballots, including those submitted by mail. Orey also said to expect legal challenges to some of those results.

Some challenges and lawsuits always follow an election, but this is another factor that has been exacerbated by the Big Lie. Election deniers are running for key races this year; Sixty percent of Americans will have one on the ballot, according to a tally by FiveThirtyEight. And more than 100 lawsuits challenging ballots and counting procedures have already been filed. A lawsuit over challenged mailed ballots in Pennsylvania could sway the outcome of key close races.

“It’s going to be a very rough couple of weeks,” Orey said. “But we have to have faith in our institutions and believe that this is going to work its way through the courts.”

On Monday, a Michigan judge denied a request by Republican secretary of state candidate Kristina Karamo — an election denier — to reject absentee ballots cast in Detroit. The lawsuit, which was filed less than two weeks before the midterms, targeted only the city, whose residents are majority Black and Democratic. About 60,000 absentee ballots had already been returned by residents.

“Such harm to the citizens of the city of Detroit, and by extension the citizens of the state of Michigan, is not only unprecedented, it is intolerable,” the judge wrote in their ruling.

Election experts say they’re also tracking instances of election workers who may be motivated by the Big Lie to sow distrust in not only what happens at the polls Tuesday, but what will happen in the days and weeks to come as results are counted, finalized, and eventually certified.

These potential diversions to the continuation of democracy are serious. Orey said it can also feel discouraging to read headlines about such ill-intentioned motives. She said people need to be cognizant of what some experts have described as “manufactured chaos.”

“It is so much easier for negative information about the elections to spread, and that is dominating all the news coverage,” she said. “But it’s leaving out the significant resilience of election administrators and election administration generally. And when we kind of buy into this narrative that, ‘The world is ending, democracy is in crisis, everything’s over,’ we are actually, I think, almost guaranteeing that that happens. … It is so reliant on people believing in our institutions.”

Tina Barton is a senior election expert for the Elections Group, which aims to build trust and stronger relationships between election officials and law enforcement. The group has worked to provide training and guides to both election officials and law enforcement ahead of Election Day.

Barton and her colleagues are monitoring certain states for any potential unlawful activity. In Arizona, alleged voter intimidation was reported at dropbox sites. Reuters reported on door-to-door canvassing in California that included intimidation. On Monday, the U.S. Department of Justice announced it was monitoring 24 states to ensure compliance with federal voting rights laws.

“We need everyone to be aware. The threats are real. The intimidation is real,” Barton said. “We’re experiencing it every single day and we need the help of everyone to do their part, to say, ‘This is not acceptable. We cannot do this, this erodes the very foundation of our country and who we are,’ and report that to someone who can do something about it.”

Amber McReynolds is a national election administration expert and a member of the National Task Force on Election Crises— a group of experts that advocate for free, fair and safe elections through preventative reforms. She is a former elections director in Colorado who checks in regularly with election officials. She said in recent days, when she has asked those officials how they’re holding up, those people just want to talk about the technical work ahead.

“It’s kind of amazing that given everything they’ve been through and everything that they continue to be attacked on, their focus is always on, ‘How are we doing our jobs? How can we do it better?”

Some people are signing up to poll workers amid everything. Porchse Miller, a community organizer in the metro Atlanta area, said she’s long wanted to be a poll worker. After a weekend of get-out-the-vote efforts, she went straight into election training.

“I love serving my people … to assist people in properly casting their ballots,” she said. “That’s how I’m going in. I’m just going in to do my part.”

Barton, who also served as an elections administrator in Michigan for 16 years, expressed appreciation for election workers. She said many have done this work for decades.

“These are people who are committed to their country. They’re doing this great service for all of us,” she said. “I would just ask everyone: As they go and cast their vote … to thank these individuals, to show them kindness, to show them gratitude.

Remembering the people behind the polls not only helps restore voters’ faith in the system, but is critical for making poll workers themselves feel comfortable and confident in playing this role in helping their communities.

“When I have worked the polls myself in the past, it was very pleasant,” said Levine, the former poll worker. “I have been thinking about it watching these midterms, that I would like to go back to working polls. … I want to make sure everyone can get to vote, without interference from poll worker bias.”