Alexa Garza has been out of prison for three years, but she still remembers how confining it felt.

“I was surrounded by walls,” said Garza, who was incarcerated for two decades starting when she was 19. “I found that reading was an escape for me. I was able to read and learn and grow, and I knew that education was the key for me.”

Already a high school graduate when she entered prison in Texas, Garza set out to obtain a higher education behind bars. That goal took the better part of her sentence to achieve. After a decade, she had earned two associate’s degrees. It took her five more years to earn a bachelor’s degree. Now a justice fellow for the national nonprofit Education Trust, which works toward education equity, Garza is raising awareness about the challenges of accessing post-secondary programs in prison, especially for women.

A recent Ed Trust report that she coauthored identifies barriers, including gender disparities, that prevent incarcerated Texans from obtaining a higher education. Men in Texas prisons have access to more than triple the number of higher education programs that women do, according to the Ed Trust report. While incarcerated men can earn master’s degrees, women just have the option of obtaining bachelor’s degrees. Only one incarcerated woman earned her bachelor’s degree in 2019, and no others have received one since, according to a spokesperson for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). He told The 19th that the department is in talks with Texas Woman’s University to develop a dual undergraduate program and online master’s degree for women, but did not provide a timeframe for when these programs might begin.

In addition to gender disparities, the Ed Trust report singles out lack of financial aid as a barrier to currently and formerly incarcerated Texans. The state won’t grant financial aid to people with felony or controlled substance convictions while they are incarcerated and for two years after their release. If these individuals want to obtain higher education in prison and cannot afford to pay for classes, they must reimburse Texas for their educational expenses as a condition of their parole. Texas also does not prevent colleges and universities from asking about an applicant’s criminal history, allowing schools to reject prospective students who have served time.

To make education more equitable for the incarcerated population, advocacy groups recommend that Texas remove financial aid barriers, ban higher education institutions from asking applicants about their criminal records and improve offerings for women. Enabling these individuals to become highly educated benefits both incarcerated people and society generally, supporters of prison education argue.

“Ninety-five percent of people in prison are getting out again, and they’re coming back to our communities,” said Michele Deitch, director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. “Education is one of the best predictors of someone staying out of the criminal justice system. If you want to have safer communities, you need to invest in education because it’s going to prevent recidivism in a very large percentage of cases.”

Prison education has been linked to a 43 percent reduction in recidivism. The more education incarcerated people receive, the lower their chance of returning to prison. Those who earn an associate’s degree have just a 14 percent recidivism rate. That number drops to 5.6 percent for individuals who obtain a bachelor’s degree, and 0 percent for those who obtain a master’s degree in prison. In Texas, about two-thirds of women lack a high school diploma when they enter prison, according to a 2018 report by the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition. Eleven percent have not completed more than the eighth grade.

Being a high school graduate made Garza an anomaly in prison, and she faced constant challenges while pursuing a higher education, she said. Initially, she was able to take a full load of college classes, but the number of classes available dwindled as the years passed. Limited course offerings in prison dragged out the time it took for her to earn an associate’s degree in business and another in general studies from Central Texas College, but she pressed on to earn a bachelor’s degree in business from Tarleton State University. She also became a certified braille transcriber while serving time.

Incarcerated at TDCJ’s Mountain View Unit in Gatesville, Garza eventually had to be transported to another unit to complete coursework because the classes she needed weren’t offered at her facility. “So a group of us, anywhere from eight to 12 of us, would be handcuffed, shackled, driven across the street,” she said. Before and after they were transported to the next facility, the women were stripped, Garza said, adding that it was difficult to access bathrooms and eat dinner on the days she had classes. “So, if I wanted to go to school, it was an ordeal.”

Garza’s family made sacrifices for her to complete her coursework. Although her classes grew increasingly expensive as the years passed and the level of academic work advanced, they paid for all of them so she wouldn’t owe money upon her release. Garza said that most incarcerated people do not have families able or willing to foot the bill for their education, so even those interested in earning degrees do not because they worry about leaving prison in debt.

“We’re already starting out with the odds stacked against us and then having an additional [burden], that’s just not cool,” she said.

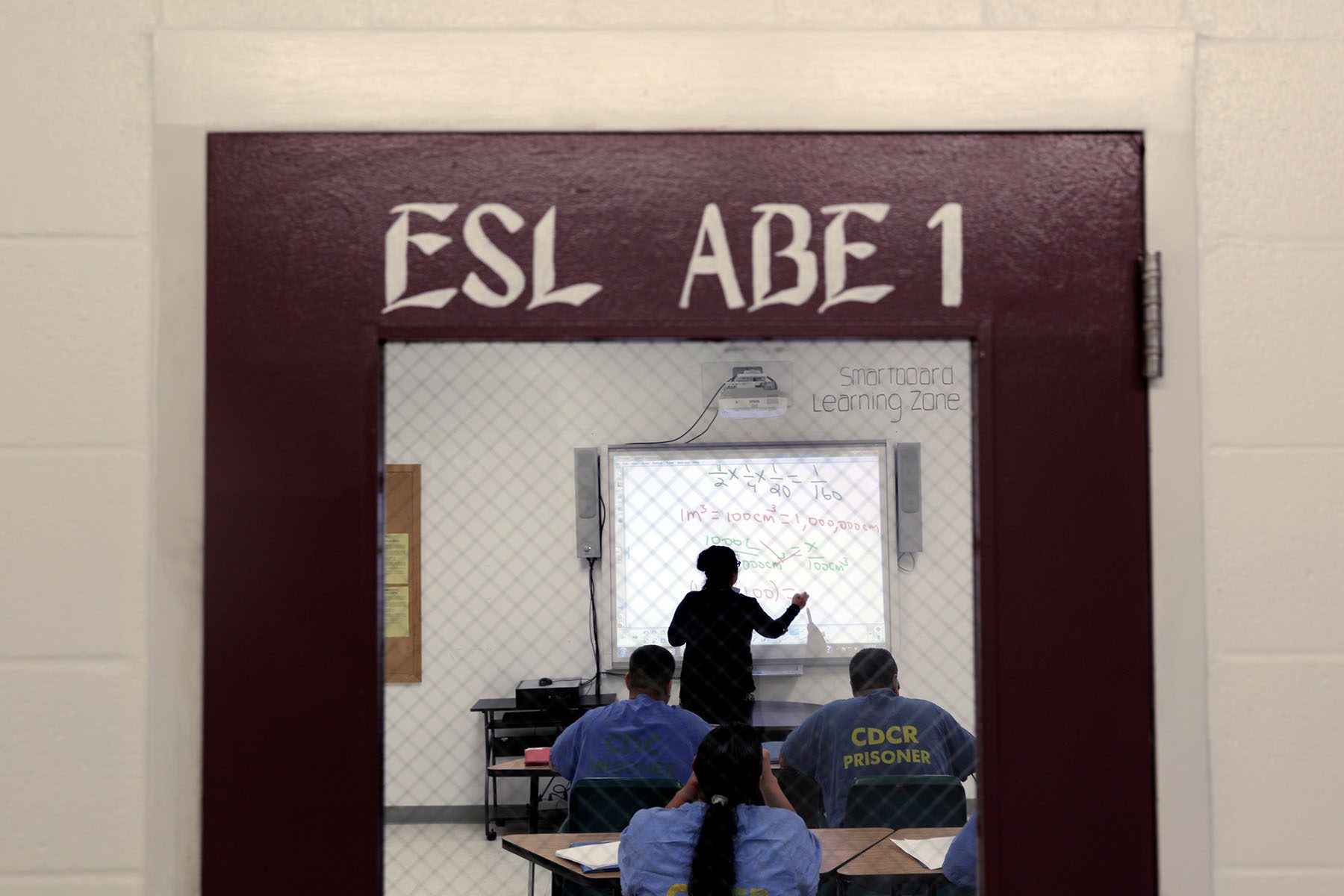

Other states have found ways to ease the burden on incarcerated people who want to receive degrees. Lois M. Davis, a senior policy researcher for the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit policy think tank, said California has several ways to cover college costs for incarcerated people. They include Senate Bill 1391, which allows California community colleges to be fully reimbursed for offering in-person courses in jails and prisons. Across the country in Minnesota, Davis said, prison industry funds cover these costs. But the real game changer, she predicts, will be the federal FAFSA Simplification Act. Starting in the 2022-23 academic year, the legislation will allow incarcerated students to receive Pell Grants worth up to $6,495 annually to pay for their education. The legislation reverses a 26-year ban implemented by a 1994 crime bill preventing incarcerated people from receiving Pell Grants.

“For every dollar invested in prison education programs, you’re saving taxpayers between $4 to $5 in re-incarceration costs, and that’s a conservative estimate,” Davis said. “The fact that these programs are so effective and and don’t cost that much makes it clear long term where you want to be investing at the community level and at the state level.”

Garza, however, believes Texas has not invested enough in women’s prison education. She said that men in Texas prisons have more opportunities to pursue certifications in career and technical education. A 2018 report by the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition found that men incarcerated in the state had access to more than double the number of technical education courses that incarcerated women did. TDCJ officials did not specify to The 19th which of its post-secondary certifications and degree programs are available in men’s or women’s prisons.

Although Garza managed to get a bachelor’s degree after years of struggle, her inability to get a master’s degree in prison still stings. Garza was filled with resentment when she would read the prison newspaper and see pictures of smiling men receiving their master’s degrees. When she asked a prison education facilitator about providing a master’s degree program for women, “I was told that a woman did not need a master’s program because our place was in the home,” Garza said.

Rabia Qutab, also an Ed Trust justice fellow, wants women to have as many higher education opportunities in Texas prisons as men do.

“In women’s facilities, it’s like you have to hit a lottery to get into [higher education] programs,” Qutab said. “They should be accessible to everyone that wants to pursue higher education.”

Qutab was already a college graduate when she entered prison in 2013 at age 24. With a master’s degree option unavailable to her, she received no educational programming while incarcerated. Upon her release in 2020, she said her criminal history disqualified her from receiving financial aid for a graduate education in Texas, so Qutab relocated to California. There, legislation prohibits colleges and universities from inquiring about a prospective student’s criminal background unless they are pursuing certain professional degrees and training in law enforcement.

Garza remains in Texas, where a public university prohibited her from enrolling in a short course because of her criminal history, she said. Hurt by the rejection, she has not applied to take any other higher education courses.

School officials should reconsider dismissing applicants who have criminal records, said Lindsay Bing, co-director of the Texas Prison Education Initiative, which gives incarcerated students in the state access to post-secondary learning.

“I think it would definitely be beneficial if we remove those barriers, and if we give people who are leaving prison more resources to connect directly to the colleges that are in the areas they’ll be returning to when they leave,” said Bing, a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. “That part of reentry is something that we could do a lot to develop, because, often, people who are leaving prison, it’s assumed that they’re never going to go to school. They’re only given information on employment and how to get a minimum wage job. This is not really doing much for our workforce when people who are incarcerated have skills and potential that we as a society should absolutely be supporting.”

Garza said that she knew earning a prison education wouldn’t remove all the obstacles formerly incarcerated people experience, but it has been a useful tool for her. In many ways, she said, her education allowed her to emotionally transcend the walls that confined her while incarcerated.

“I needed all the help that I could get because I’m a convicted felon,” she said. “So that’s how I looked at education, as more like me being able to free myself and learn and grow. For the people that really tried to learn a skill set while inside, it was a different culture. We were there, but we weren’t there. We had hopes and dreams.”