For the first time ever, the majority of people who got an abortion in 2020 used medication abortion — a two-pill regimen that can be safely administered from home — per preliminary data analyzed by the Guttmacher Institute, a Washington-based organization that studies reproductive health policy.

The shift comes at a pivotal moment for abortion access. The Food and Drug Administration has recently taken steps to make medication abortions more available, including allowing doctors to prescribe the pills through telemedicine, meaning they can be mailed to a patient without an in-person visit. The change, long advocated by medical experts, could dramatically expand access to the procedure, especially for patients who live far from a doctor’s office.

But at the same time, the U.S. Supreme Court is weighing one of the greatest challenges to abortion rights in decades: a case that many experts believe could be used to undo some or all of the abortion rights protection created by the 1973 case known as Roe v. Wade. A decision is expected this summer. If Roe is completely overturned, states could have the power to ban abortion entirely. Even a partial weakening could allow states to further restrict access to the procedure. And in anticipation, some Republican-led states are working to pass new abortion bans and to limit access to medication abortion in particular.

It’s unclear which trend will have a greater impact.

“We’re looking at some real potential for medication abortion. It’s very clear that you can use telelhealth for medication abortion. The evidence is there, the science is there, it is safe and effective,” said Elizabeth Nash, who helped write the Guttmacher paper and tracks state policy for the institute. But at the same time, “the Supreme Court is poised to overturn abortion rights, but you can access medication abortion on the internet. And because it’s safe and effective, then it becomes a possibility for people to access care when they can’t get it elsewhere.”

The data comes from Guttmacher’s triennial survey of abortion facilities. The newest dataset reflects abortions performed from 2019 to 2020 and is still being completed. But researchers have data from 75 percent of all clinics, enough to conclude that more than 50 percent of all abortions are now obtained via pills.

It’s a significant shift. In 2017, the last year for which Guttmacher had data, 39 percent of abortions were performed through medication, while 61 percent were done through surgery. Pills are less expensive than surgery and are far less invasive. In general, both medication and surgical abortions have low complication rates.

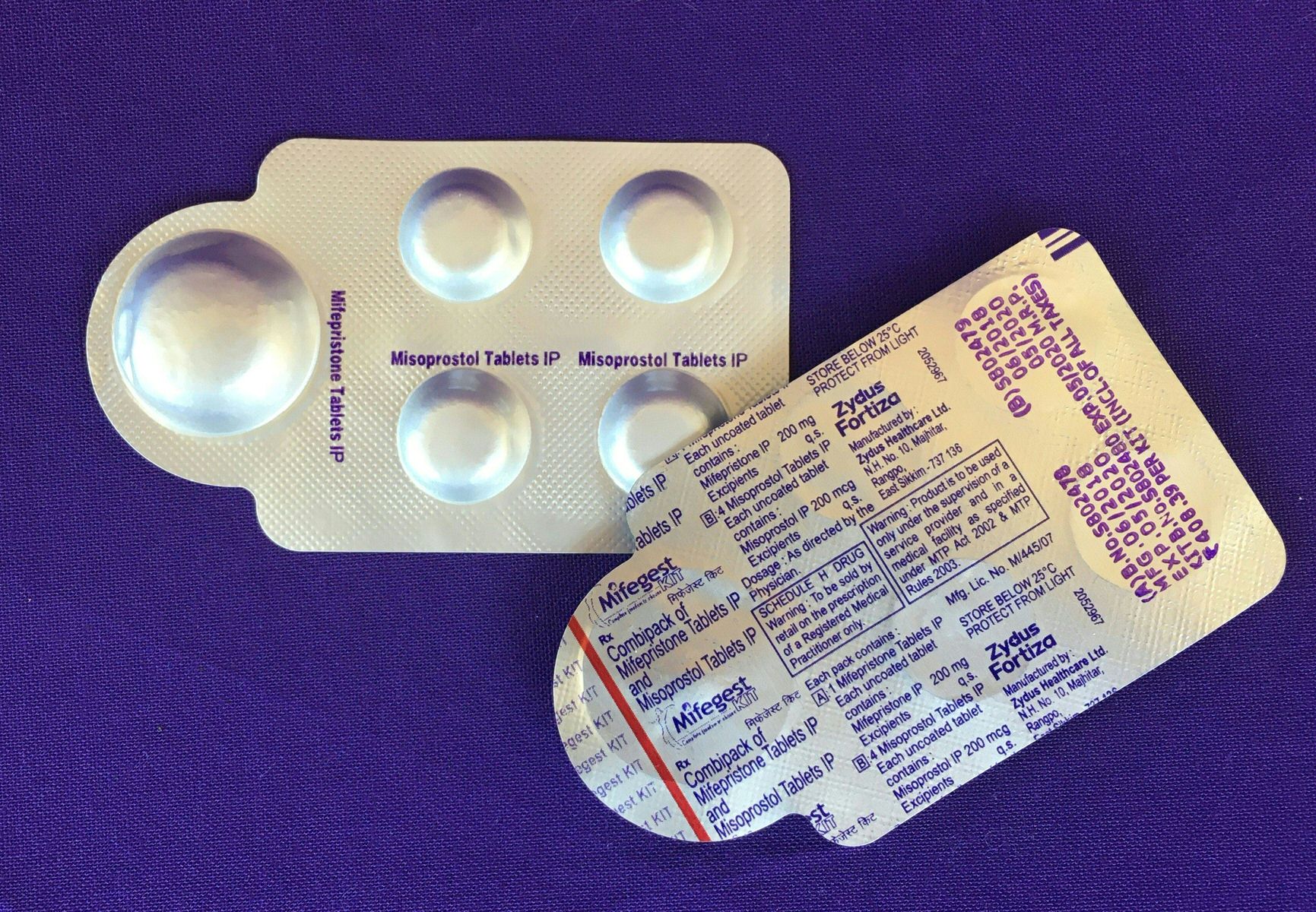

The two-pill medication abortion option has been available since 2000. Patients take mifepristone first, and then 24 to 48 hours later, follow up with another pill, misoprostol. The FDA has authorized the two-pill process for people up until their 10th week of pregnancy. But evidence about the pills’ safety has encouraged some doctors to prescribe them off label for people in their 11th week as well, at the end of the first trimester. The vast majority of abortions take place before the 13th week of pregnancy, per data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Until 2020, patients had to visit the doctor at least once to receive a medication abortion. But the FDA temporarily waived the in-person visitation requirement as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Though medication had already begun making up a larger share of abortions, that policy shift likely accelerated the trend, per Guttmacher.

The shift could be permanent and have longer-term implications. This past winter, the FDA moved to permanently get rid of the requirement that someone pick up mifepristone in person and moved to expand the number of pharmacies that can dispense the pills.

“Being able to mail the pills due to the pandemic changed the game. It made telehealth much more of a possibility in many many places,” Nash said. “Of course, this is more available in states that haven’t banned telehealth or medication abortion. But nonetheless, this is a very, very big step forward.”

Still, even as the federal government has sought to remove barriers, some states are trying to restrict access to the pills. Though the FDA has sought to eliminate in-person prescribing requirements, 19 states have laws that ban telemedicine as a way to provide medication abortions.

Last year, Texas implemented a new law banning medication abortion after seven weeks of pregnancy. Currently, Guttmacher is tracking bills in 16 states that would limit medication abortion in some way, Nash said. In South Dakota, the legislature is debating a bill that would prohibit medication abortion entirely — legislation that would likely violate Roe v. Wade. Georgia’s state Senate is voting Thursday on a bill that would prohibit using telemedicine for medication abortion.

As more states move to restrict abortion access — and with a Supreme Court generally viewed as hostile toward abortion rights in general — some reproductive rights advocates have suggested that expanding access to mifepristone could help fill in some of the gaps.

In some states, abortion rights advocates are working to build networks of people who can help pass on advice on how to access medication abortion and terminate their pregnancy without a doctor. (Such a practice, known as “self-managed abortion,” is safe if done correctly, and is endorsed by the World Health Organization, though three states have laws that criminalize the practice, per the advocacy group If/When/How.)

Some legal scholars have suggested that the FDA could attempt to overrule those bans by arguing that its policies approving medication abortion are an extension of federal law and therefore preempt state limitations, though it’s unclear if that would stand up in court. If it did take effect, though, such policy could make it impossible for states to fully ban abortion, or at least impossible to ban abortion in most of the first trimester.

“If the Supreme Court does overrule Roe, there is more urgency for the Biden administration to pursue arguments like this,” Greer Donley, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, previously told The 19th.