For nearly a century, Black History Month has been a time to celebrate the achievements of groundbreaking people who have shaped our country’s history. Much of this focus is on trailblazers like Kamala Harris, civil rights pioneers, advocates, politicians, policymakers and entertainers from Beyoncé to Cardi B.

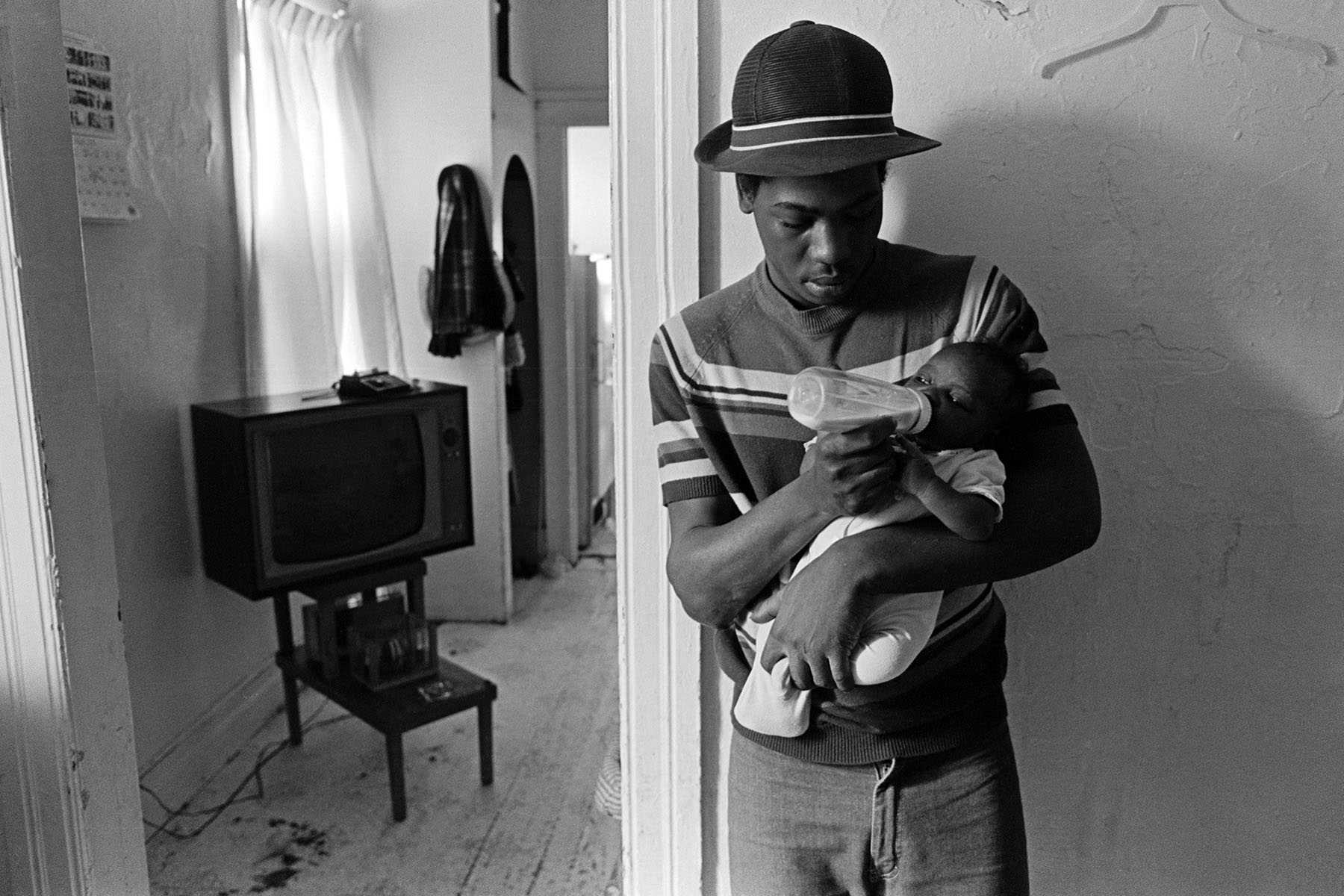

But as those leaders spoke to crowds and infiltrated halls of power, millions of Black people lived their lives and made their own history. Often those contributions were more humble. Even simply celebrating the things and people closest to them in ways that might not have been accessible to previous generations — from birthday and retirement parties to navigating grief or simply having a picnic at a park — served as markers of progress.

(Click to expand the photos for caption information.)

This Black History Month, in addition to highlighting lesser-known Black leaders like Lois Curtis and Amalya Lyle Kearse, The 19th wanted to showcase the everyday, lived experiences of Black Americans in the United States dating back to the earliest days of the 20th century to 2022.

In the early 20th century through the 1960s, Black Americans built lives in the South and pockets of the Midwest and Northeast as more opportunities were created in various labor jobs and trades.

As constitutional amendments granted more Black men the right to vote, Black women were still left out — even with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. Jim Crow laws kept Black people from fully accessing the polls.

Still, life went on and thinkers and artists thrived in cities like New York (via the Harlem Renaissance) and Chicago (as jazz and blues — and, later, house music — flourished).

Schools began integrating in 1954 after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling, student and faith-based movements took to the streets to demand rights: like desegregating public transit and businesses, and better wages and job opportunities.

The civil rights movement became a steady motivating force in the South and in other parts of the country. The Freedom Rides took place during the summer of 1961 and the March on Washington in 1963.

Although they were not often given the same spotlight as men, Black women were at the heart of many of these protests and demonstrations, including college students like Catherine Burks-Brooks during the Freedom Rides and Black women in sororities, who played a pivotal role in the suffragist movement.

As time went on and legislation like the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was approved, Black Americans sought more opportunity and became more vocal about the idea of Black power in the 1970s and ‘80s. The Black Panther Party, Pan-Africanism and other movements sought to empower communities and to demolish systems that kept Black people in poverty with no opportunities for advancement.

Black culture evolved and became a major part of the fabric of American life in politics, sports and music in a way that was much less stifled than in the earliest decades of the 20th century.

Writers and intellectuals like Audre Lorde and James Baldwin challenged existing structures and shared experiences of queer Black folks. James Brown created a hit with “Say it Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud.” Athletes like Muhammad Ali crossed paths with figures like Malcolm X and Sam Cooke. Black culture featured prominently on screens and blared from radios across the country.

- Public school students on a class trip smoke cigarettes and strike poses outside a Manhattan television studio in January 1965. (Harvey L. Silver/Corbis via Getty Images)

- Two young boys eat during a free breakfast for children program sponsored by the Black Panther Party in New York City in 1969. (Bev Grant/Getty Images)

The latter part of the 20th century also heralded growing visibility for Black LGBTQ+ Americans as they shaped major movements like the fight for civil rights, Pride celebrations and HIV/AIDS activism.

That increased visibility often meant violence and marginalization. Contributions of leaders like Bayard Rustin, an organizer who spearheaded planning of the March on Washington, and Marsha P. Johnson, a trans activist who played a key role in the 1969 Stonewall uprising, were only fully highlighted long after they passed.

As leaders in the early part of the 21st century to the present day fought to combat racist policing policies, redlining, the worst impacts of the war on drugs, economic inequity and a global pandemic, Black Americans continued to write their own history in ordinary and extraordinary ways.

- Shelly Phillips holds niece Kimmore Barthelemy in the FEMA Diamond travel trailer park in May 2008 in Port Sulphur, Louisiana. Phillips lost her home and job in Hurricane Katrina and is raising four children. (Mario Tama/Getty Images)

- A couple sits in the grass during a New York City Pride March in the 1990s. (Mariette Pathy Allen/Getty Images)

Babies were born and cuddled by grandmothers and aunties, children laughed, parties and funerals were held, and Black people continued fighting: from Block Club meetings before local aldermen — many of those meetings led by Black women — to the halls of Congress.

Black history continues to be made. Not all of it is by people honored on stamps or quarters, or by folks who created legislation or founded institutions. Sometimes, it was made by the kid on the block who ran the fastest from one stoplight to the next, or the church mother who raised a record number of donations at a fish fry fundraiser.

- Ka’miyah Buck, 9, cheers while watching a pig race at the Mississippi State Fair in October 2020, in Jackson, Mississippi. (Wong Maye-E/AP)

- Cheerleaders from the Houston Sassy Pantherettes prepare to perform in the 28th Annual Martin Luther King Jr. Grande Parade in Houston, Texas, in January 2022. (Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

Those moments, from the mighty to the mundane, make up Black history.