A decades-old legislative effort to recognize the Equal Rights Amendment and its protections against gender discrimination has entered a new year with a revived legal fight.

Democratic attorneys general for Illinois, Nevada and Virginia filed arguments this month as part of an appeal to a 2020 lawsuit to formally recognize the Equal Rights Amendment.

A district court judge dismissed the suit last year, saying that “laudable as their motives may be,” the attorneys general did not have legal grounds to sue and that a seven-year deadline set decades ago by Congress to ratify the amendment had expired. On Monday, the ERA Coalition and other equity-focused groups filed an amicus brief offering formal support for the appeal.

“Our hope is that this amicus brief will convey why it’s appropriate to allow a longer time than seven years for a civil rights and cultural change like the one the ERA reflects,” said Linda Coberly, an attorney and chair of a legal task force for the ERA Coalition, which says it is made up of nearly 200 organizations.

Supermajorities in both chambers of Congress ratified the Equal Rights Amendment in 1972 following decades of advocacy. The ERA text reads in part: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

ERA advocates believe that despite some court rulings affirming protections against gender-based discrimination in recent decades, the amendment is still necessary to address legal loopholes around discrimination in work as well as domestic and sexual violence.

The lawsuit specifically challenged the actions of the United States archivist, a federal employee who publishes new amendments to the U.S. Constitution when requirements are met under Article V of America’s founding document.

In January 2020, after Virginia became the 38th state to ratify the ERA (the threshold needed for an amendment to be added), the archivist refused to certify it. The U.S. Department of Justice at the time issued an opinion citing the passed deadline.

The attorneys general argue in their new legal filing this month that the archivist’s refusal to make the ERA the 28th Amendment establishes the legal framework for the lawsuit to proceed.

“The ERA has been properly ratified by the states and any attempt to prevent its inclusion in the Constitution is without basis in law,” Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring said in a statement. “The Equal Rights Amendment will finally ensure true equality in our nation’s foundational document and correct an injustice of historic proportions.”

The future of Virginia’s legal involvement in the ERA is unclear. Herring is leaving office this week after losing reelection in November to Jason Miyares, a Republican former state lawmaker who voted against ratifying the ERA in 2020. On January 6, Herring issued an opinion that Virginia cannot rescind its 2020 ratification.

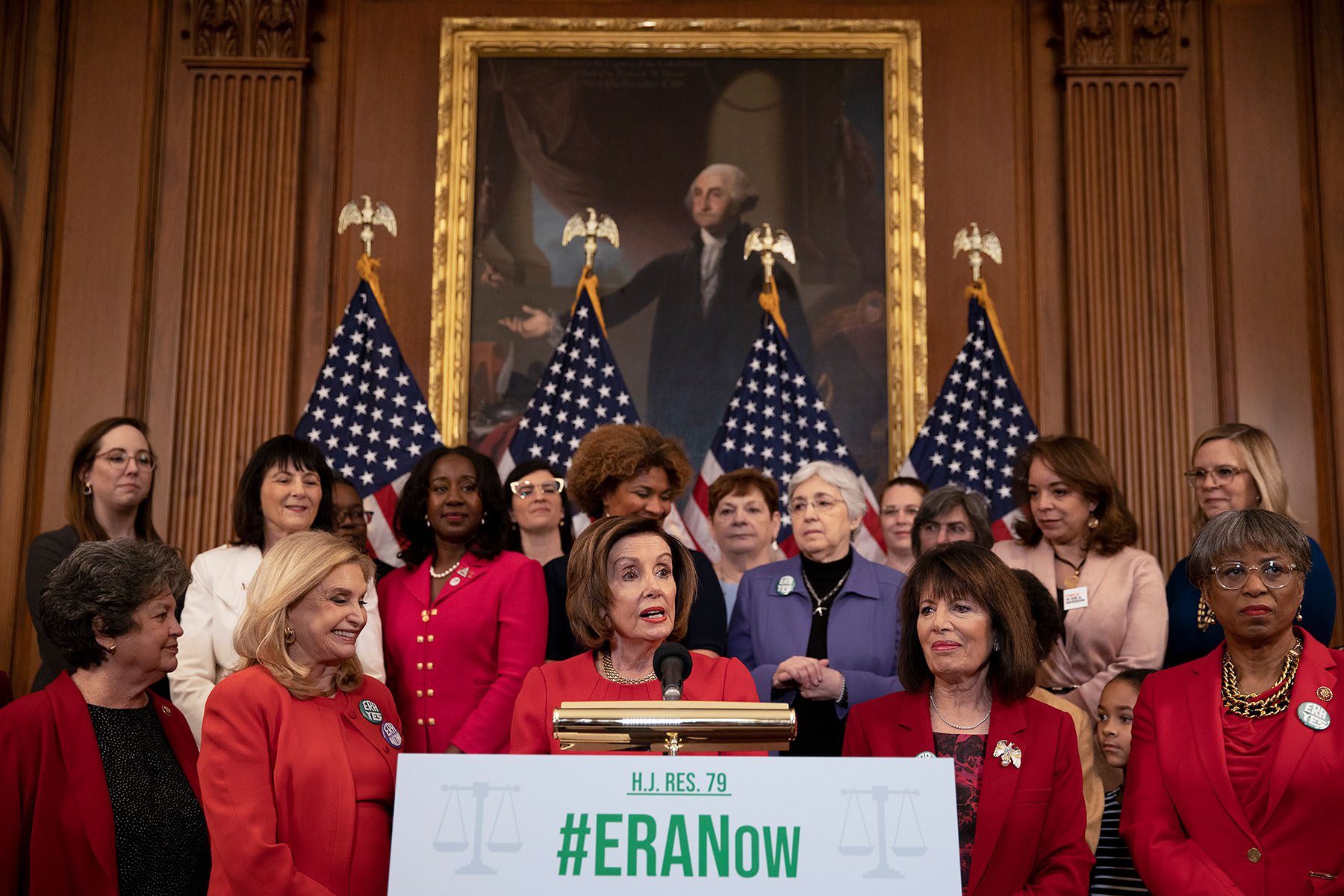

The attorneys general also claim in their amicus brief that “Congress lacks authority to impose a timeline for ratification in this manner.” ERA advocates have been lobbying Congress to remove any deadline associated with the amendment. Democrats in Congress overwhelmingly back those efforts, advancing a resolution in the House. The effort is stalled in the more evenly split Senate, where it would need 60 votes but just a handful of Republicans have expressed public support.

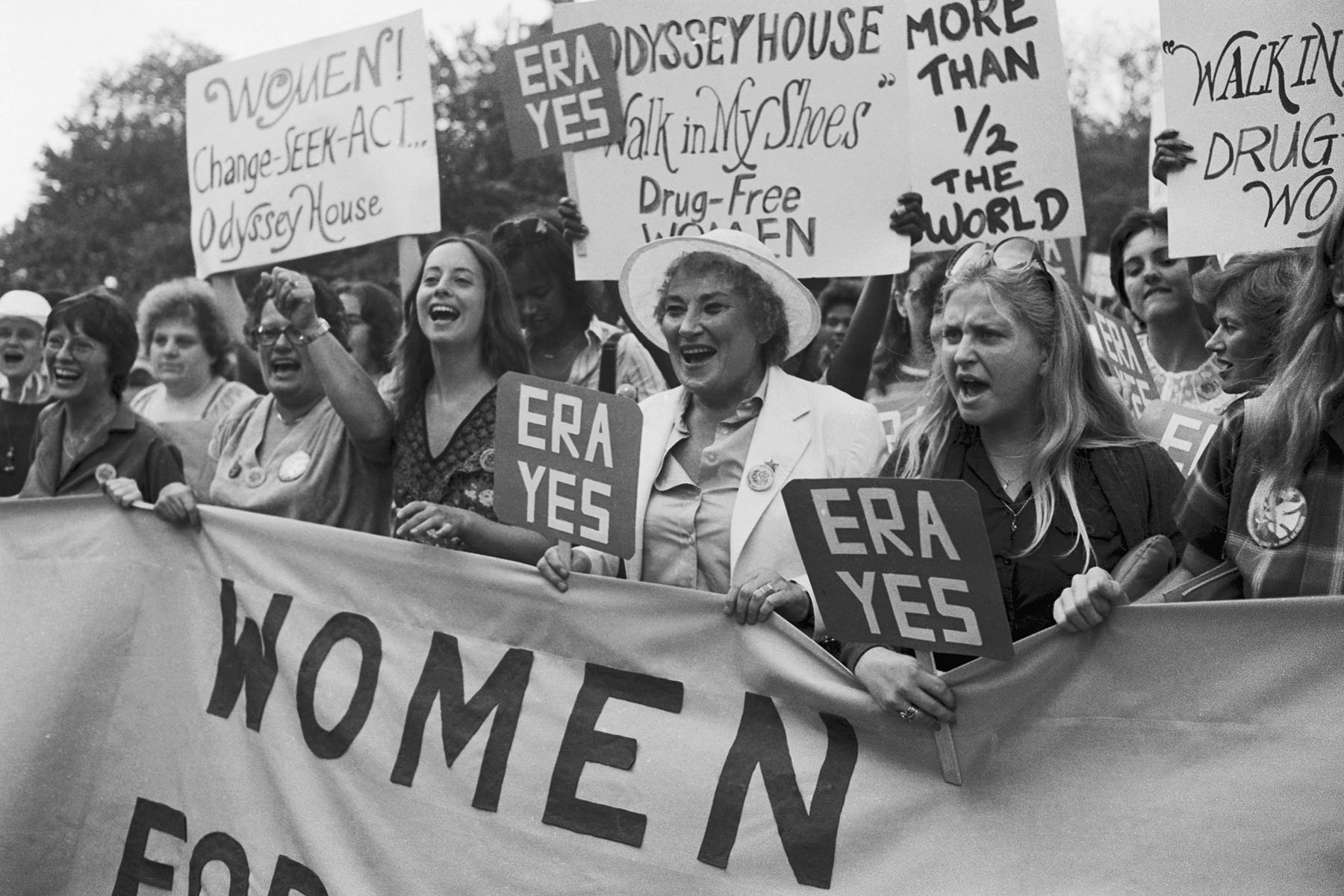

Nearly 50 years ago, Congress gave state legislatures seven years to ratify the amendment. (The use of time limits in amendments began in the 1900s, and debate over the ERA in particular advanced in part because of the deadline.)

Under rules for amending the Constitution, three-fourths of state legislatures, or 38, must ratify an amendment for it to be adopted. Despite 30 states ratifying the amendment within the first year, a public campaign to oppose the ERA, led in part by Phyllis Schlafy, halted its momentum. Schlafy and others claimed the amendment would remove various legal protections for women. In recent years, opposition has focused on the legal ramifications of the ERA on abortion rights.

A three-year extension by Congress, a move that separately was legally challenged, did not result in more states ratifying the amendment.

Decades later, a grassroots movement led by women of color and LGBTQ+ people renewed ratification efforts in state legislatures. In 2017, Nevada ratified the ERA, followed by Illinois in 2018 and Virginia in 2020.

ERA advocates including Coberly believe the amendment is already a part of the Constitution because the key requirements — approval by Congress and state legislatures — have been met and Article V does not specify otherwise. Legal scholars have highlighted the winding path of how some amendments have been added to the Constitution, including the fact that the 27th Amendment was added more than 200 years after Congress originally ratified it.

“There’s been all kinds of messes over the years about the amendment process. It’s not a tidy process,” Coberly said. “So the fact that this is all going on with the ERA — it’s actually not that unusual. I mean, the last amendment that was put in the Constitution was proposed by James Madison. And it took 203 years to ratify.”

Groups including National Right to Life have argued that the ERA would be used to defend abortion rights. The organization has pointed to decades of court rulings to argue that the deadline initially set by Congress cannot be retroactive and lawmakers should start over.

“To adherents of the ERA-never-dies movement, it makes perfect sense to disenfranchise the current generation of state legislators, while claiming ownership of the long-expired actions of their predecessors of a half-century ago,” wrote Douglas Johnson of National Right to Life on the group’s site. “The same mindset deludes them into believing that the current Congress can time-travel to 1972 to revise the legislative compromise that produced the two-thirds votes for the ERA Resolution — even though not a single member of the 92nd Congress remains in Congress today.”

Separately, several states have rescinded their prior ratifications of the ERA, arguing in court filings related to the 2020 lawsuit that the amendment is not a part of the Constitution. The district court judge did not address this issue in his ruling. ERA supporters have countered that other efforts to rescind an amendment — particularly, some states rescinded their support for the 14th Amendment — were still counted toward the three-fourths threshold.

Other issues abound as the attorneys general’s lawsuit goes through the appeal process. Coberly of the ERA Coalition noted that additional language in the ERA text states that the amendment takes effect two years after final ratification — in this case, January 27, 2022, which marks when the Virginia legislature finalized its approval of the amendment in 2020.

Coberly said people could file lawsuits after that seeking relief from gender-based discrimination under the ERA, opening up new legal questions.

The federal government has several weeks to respond to the latest legal arguments. The appeal process is expected to take several months.