This article has been updated.

The leaders at Time’s Up, an organization founded to fight sexual misconduct and advocate for gender equity in the workplace, often tell staff that their own proximity to power is a strength, not a hindrance.

“The power of Time’s Up is that Time’s Up is in rooms no one else is,” said one former staffer, paraphrasing the mentality they say they heard from President Tina Tchen and other leaders.

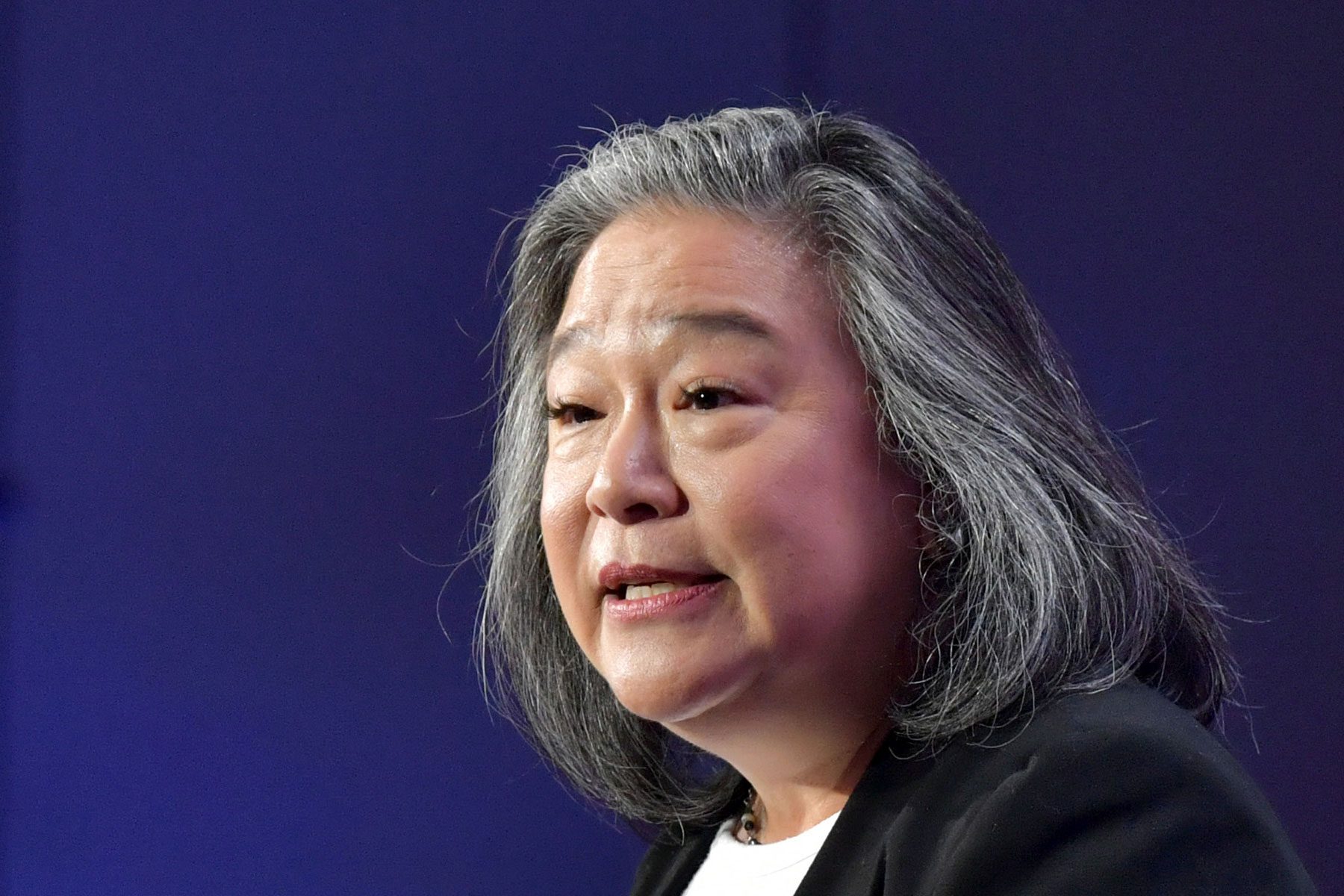

Tchen, in her first interview since Time’s Up Board Chair Roberta Kaplan resigned over her assistance to Democratic New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo as he attempted to discredit a former staffer who accused him of sexual harassment, said she has “learned from this about a blindspot I had” about some of the group’s leaders’ longstanding relationships with people in powerful positions.

Tchen said in the wide-ranging interview that she now sees it can be difficult to gauge at what point in a working relationship Time’s Up may need to pull away as new information about an individual or organization comes to light.

“When do we say ‘No, we can’t work with you anymore’?” Tchen asked. “I will admit, I probably have drawn that line too far down the pathway.”

Tchen’s interview, in which she discusses the resignation of Kaplan, along with Time’s Up’s achievements, challenges, missteps and relationship to power, was recorded on Friday as part of The 19th Represents, an online summit taking place this week.

In the interview, which airs Thursday, Tchen discusses how the country is at a “transformational moment” as congressional Democrats aim to pass President Joe Biden’s caregiving package and how the organization’s “theory of change” may recalibrate in the wake of a report on Cuomo.

Tchen said that until now, Time’s Up aimed to use its access to “work with people who can make change, and hold them accountable.” She has “seen it work,”she said, citing individual corporate executives who enacted paid leave policies while national legislation stalled. “But clearly, we need to do that in ways that are much more careful.”

“I acknowledge this, and it is painful to me, that actions that I have done have caused survivors to feel pain and to feel betrayed,” Tchen said. “We need to figure out: How can we do this to make sure that doesn’t happen?”

The answer will not be a decision that’s made unilaterally, she added.

“I don’t have an announcement to make that we’ve hired somebody to do this, because I actually think that in and of itself is something we want to change — which is just the board deciding it’s going to hire this person, then we move forward,” Tchen said.

When New York’s attorney general released a 165-page investigative report earlier this month finding that Cuomo had sexually harassed 11 women and retaliated against one, it was a bombshell that sent ripples through the advocacy communities for women and LGBTQ+ people.

Kaplan, a prominent lawyer who successfully argued for marriage equality before the Supreme Court, was among several notable advocates who, according to the report, advised the Cuomo team as they made plans to draft and disseminate an op-ed letter challenging the credibility of former staffer Lindsey Boylan, the first to publicly accuse the governor of sexual harassment. Another advocate was Human Rights Campaign President Alphonso David.

Kaplan’s involvement, even after her resignation, has thrust into the spotlight concerns about Time’s Up’s belief that it can hold powerful people to account from the inside. The organization’s initial response exacerbated those concerns.

“We’ve worked to hold power accountable in board rooms, in the halls of government, and in organizations big and small, and we have felt uniquely capable of doing so because many of us have worked in those very institutions,” Tchen wrote in that statement. “We have never felt co-opted by that experience, only informed by it to try new strategies.”

More than 100 survivors of sexual harassment and assault, including former Time’s Up staffers and Legal Defense Fund clients, wrote an open letter to the Time’s Up board and the National Women’s Law Center, which administers the defense fund. In the letter, they argued that the organization has “lost its way” and directly called into question its notion of working with the powerful.

“There is a consistent pattern of behavior where the decision-makers at Time’s Up continue to align themselves with abusers at the expense of survivors,” the group wrote, calling for a third-party investigation and for the group to cut ties with any leaders aiding “perpetrators of harm.”

In interviews with The 19th over the last week, more than a dozen current and former Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund clients, staffers, consulants and members of various working groups said they’ve repeatedly raised concerns about the organization’s potential conflicts of interest and political alignments. Until the Cuomo report, they were dismissed, they said.

“People make mistakes, but these are repetitive mistakes that have the same problems around them,” said Dr. Pringl Miller, one of the members of Time’s Up Healthcare who resigned earlier this year over the group’s response to allegations that board member Dr. Esther Choo failed to report the sexual harassment of a colleague at Oregon Health & Science University. The health care group was told Kaplan would represent Choo in the matter.

“I don’t understand how these people in high-up leadership positions, who interface with people who have a lot of power, are not keeping their priorities straight — maybe it’s not possible in those circles,” added Miller, who went on to found Physician Just Equity, which provides peer support to doctors on workplace issues.

A group of high-profile Hollywood women launched Time’s Up in early 2018 several months after the New York Times published its first story about how Hollywood film producer and Miramax co-founder Harvey Weinstein paid off women who accused him of sexual harassment.

The co-founders of its legal defense fund, which at that point had already brought in $13 million from a Go Fund Me campaign, were Tchen, Kaplan, Fatima Goss Graves and Hilary Rosen. Goss Graves heads the National Women’s Law Center, which administers the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund. Rosen is the vice chair at SKDK, a well-known Democratic strategy firm based in Washington. They are both on the Time’s Up board.

Time’s Up’s leaders and the members of its board came into the #MeToo movement with storied careers in politics and business. Tchen, a Chicago-based lawyer, was a top fundraiser for President Barack Obama who joined him in Washington, going on to become Michelle Obama’s chief of staff, then executive director of the White House Council on Women and Girls. Kaplan was a Supreme Court litigator who wrote a book about successfully arguing for same-sex marriage. Rosen, before joining SKDK, was a chief of staff to Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein and chair and chief executive of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), a lobbying group.

At times, some of these women’s past alliances and continued professional endeavors presented potential conflicts that Time’s Up staff, clients and associates felt should be reviewed, disclosed, or both, those interviewed by The 19th said.

Kaplan, through her law firm Kaplan, Hecker and Fink, represents E. Jean Carroll in her defamation lawsuit against former President Donald Trump, who she says sexually assaulted her in the 1990s. Carroll praised Kaplan’s work on the day of her resignation. But Kaplan is defending Goldman Sachs in a lawsuit that claims the investment bank’s general counsel covered up sexual misconduct claims against another member of its legal department. She is also representing top Cuomo aide Melissa DeRosa, who was central to the governor’s attempt to quash sexual harassment allegations and discredit Boylan. DeRosa resigned last Sunday. Cuomo followed on Tuesday.

-

More from The 19th

- Time’s Up leader resigns over involvement in Cuomo sexual harassment response

- #MeToo exposed how forced arbitration protects harassers. A bipartisan group of lawmakers wants to ban it.

- Newsrooms are failing to protect women journalists. Survivors hope Felicia Sonmez’s lawsuit will change that

Tchen said in the 19th interview that it was her understanding that Kaplan began representing DeRosa in a nursing home scandal related to Cuomo’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis because they were worried she would be “scapegoated” and “at the time it did not seem like a red flag.”

But Kaplan’s representation of individuals and entities who are not themselves accused of misconduct but potentially helped cover it up sustains workplace cultures where women often face near-insurmountable barriers to bringing claims without fear of ruining their careers and reputations, critics told The 19th.

Tchen’s stature in politics both in Chicago and nationally has also led to situations where Time’s Up staff, consultants, defense fund clients and other survivors worried that political relationships were being prioritized over the survivors’ needs, they said.

Ahead of the 2019 Chicago mayoral election, Tchen, who was not yet president of the organization, in February endorsed Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, who went on to lose to now-Mayor Lori Lightfoot. Preckwinkle’s campaign touted support from the “co-founder of #TimesUp Legal Defense Fund” and used the group’s name on campaign literature. Preckwinkle had in September 2018 fired her chief of staff for what she called “inappropriate behavior,” saying at the time she acted quickly after learning of allegations he had groped a woman in late 2016. The Chicago Tribune reported in November 2018 that Preckwinkle knew of the incident as early as March of that year. After firing Keller and launching her mayoral campaign, Preckwinkle went on to convene a county working group to examine sexual harassment policies that Tchen was tapped to advise in her capacity as a lawyer at the firm Buckley LLP, just days after endorsing Preckwinkle’s mayoral candidacy.

Tchen told The 19th that she endorsed Preckwinkle in a personal capacity because the women had worked together for 30 years and she believes she acted swiftly once learning of allegations against her chief of staff. Tchen subsequently became president of Time’s Up in October 2019 when its previous chief executive, Lisa Borders, resigned after her son was accused of sexual misconduct. Tchen said now that she is president, her role should be different, but “I actually don’t think that we should hamper the work of our staff” who want to engage in the electoral process on their personal time.

“And yet, this is an area we are now learning, this is a learning process for us, and that can be fraught, too,” Tchen said, adding that the standard conflicts-of-interest policy the organization uses “isn’t sufficient.”

Internal concerns about potential conflicts between the organization’s work and the political allegiances of its leaders intensified during the 2020 Democratic presidential primary. Senior staff rejected suggestions that they should take a formal leave of absence in order to work on or advise a campaign or endorse candidates, according to former staffers.

Jen Klein, who was then Time’s Up’s chief strategy and policy officer, advised Biden’s campaign on gender policy. She now co-chairs the White House Gender Policy Council. Both she and Tchen donated to Biden’s primary and general election campaigns. Staff worried about the optics of April 2020 donations of $2,800 from Tchen and Klein — the maximum allowable primary campaign donation — because they landed shortly after the New York Times published a story about former Senate aide Tara Reade’s allegation that Biden sexually assaulted her. Biden denied the claim.

Staff also told The 19th they took notice when Rebecca Goldman, who at the time was Time’s Up’s chief operating officer, weighed in on whether the organization’s social media platforms should highlight a debate exchange between Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Michael Bloomberg over his company’s use of nondisclosure agreements, known as NDAs. Goldman’s husband’s political firm, Three Point Media, was paid about $450,000 for Bloomberg’s three-months-long presidential campaign.

Time’s Up has long criticized the use of NDAs, which can prevent survivors of sexual assault and harassment from making their claims public. Ahead of and after early Democratic debates, Time’s Up used its Twitter account to repeatedly criticize moderators for not bringing up the issue of sexual harassment and assault in the workplace. But in February 2020, when a debate moderator asked Bloomberg whether his company was a hostile workplace for women, staffers were advised not to tweet, they said. After Bloomberg offered to release three women from their NDAs, Time’s Up said in a related press release that it “commend[s] all companies taking meaningful action to fight the epidemic of sexual harassment and discrimination.” Time’s Up used its Twitter account to thank Warren for highlighting the issue two weeks later when she exited the presidential race and Bloomberg was already out.

In a written response to questions for this story, Time’s Up reiterated that staff have a “right as public citizens to be engaged in personal political activity” and that “they should be able to do so regardless of where they’re employed,” but did not weigh in on specific actions its staffers have taken.

Time’s Up’s close ties since its founding to SKDK, which brought in more than $2 million from Biden’s campaign alone, have also been a point of friction between the organization and some of its associates and legal defense fund’s clients.

The National Women’s Law Center runs the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund and therefore makes intake decisions and matches survivors with attorneys. Clients can then apply for public relations or “story-telling assistance” and those requests are routed through SKDK, which either handles a client internally or matches them with an outside PR firm. SKDK employees, including Rosen, are often on Time’s Up foundation strategy calls. Clients have no way of knowing whether SKDK’s political or corporate consulting work relates to an individual or entity they may be suing for harassment. Current and former legal defense fund clients told The 19th they would like a greater degree of transparency about potential conflicts.

“I understand that the fund’s relationship with Time’s Up foundation can be confusing,” Uma M. Iyer, a spokesperson for the legal defense fund, told the 19th. “However, the work of and decisions made by the fund happen completely independent of Time’s Up; we are separate organizations with separate staff. The fund remains a place for survivors to turn to, and I urge folks to continue to reach out to us for both legal and PR assistance.”

Dominique Huett, a current member of the Time’s Up Safety Working Group, said of the Time’s Up foundation: “The fact they’re even aligned with the Democratic Party is pretty biased to begin with. They need to be nonpartisan. That’s been a critical flaw from the very beginning.” Huett filed a civil lawsuit against Weinstein and the Weinstein Company, which she said was complicit.

Lauren Weingarten, a Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund client who recently settled a case against CBS, said she “literally felt like the floor was falling out beneath me” when she realized SKDK works with the network, and that CBS was one of Time’s Up’s strategic partners. It would have made a difference if someone from Time’s Up or the legal defense fund had walked her through ties to CBS and assured her it would not impact her case, she said.

Tchen told The 19th that reviewing and disclosing potential conflicts “is the kind of thing that’s on the table to take a look at, to make sure we put in whatever guardrails and protections and policies that we need to.”

Advocates for survivors worry that even perceived conflicts could discourage people from going to Time’s Up or its legal defense fund with their cases if they are not disclosed and explained. Survivors of sexual misconduct in the workplace are already navigating power structures that make it difficult for them to come forward. Many have watched as colleagues close ranks to protect their abusers, have experienced whisper campaigns that damage their credibility, and faced threats of retaliation, or worse. Time’s Up is often the only place someone without the financial resources to mount their own case can go, they said.

Shaunna Thomas, the co-founder and executive director of UltraViolet, a progressive activist group that fights sexism, said the “stakes are high” as survivors watch how Time’s Up handles the fallout from the Cuomo report.

Tchen said as the organization works to regain the trust of survivors she would “urge folks not to forego seeking assistance that they may need both on the public relations side and on the law firm side.”

Tchen says Time’s Up is now in listening mode. The organization has solicited input from the survivor community and wants even the parameters of the accountability process to be participatory. Several survivors told The 19th they had already submitted feedback or contacted Tchen directly.

“I believe her intentions are good and her heart is in the right place, ” said Pamela Guest, a member of the Time’s Up Safety Working Group who said survivors now need to see “action” to develop an accountability process.

“I understand people are waiting to see what that looks like. That’s the reason we are going to try to start to put ‘What does that proper design-process process look like?’” Tchen said.

“It may not feel fast enough for people,” she added, “but actually, right now, I think that’s what we want to do and it will absolutely involve outside people.”

Disclosure: Human Rights Campaign and Hilary Rosen have been financial supporters of The 19th.

Correction: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized Fatima Goss Graves’ relationship to the National Women’s Law Center. She is president of the center and co-founded the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund that it administers.