Sixty years ago, on March 7, Sheyann Webb-Christburg walked with 600 other activists in Selma, Alabama, to protest Black voter suppression. As they reached the Edmund Pettus Bridge, just six blocks into their 54-mile march to the state capital of Montgomery, Webb-Christburg’s heart began to beat faster.

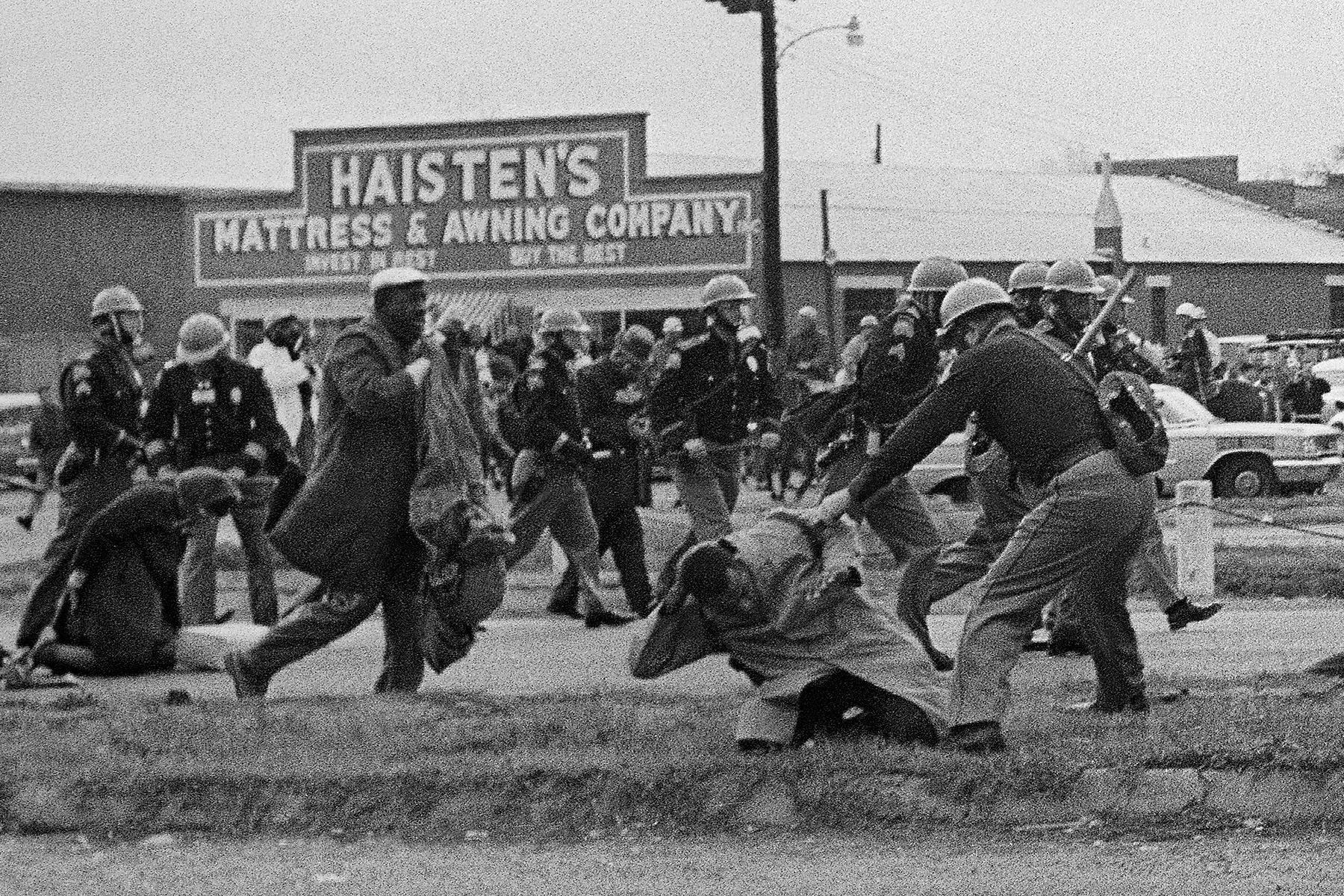

She saw police lined up at the bridge’s entrance, wearing tear gas masks and holding billy clubs. Watching the police with their horses and dogs in tow, Webb-Christburg took in the scene.

She knew something terrible was going to happen.

As they walked closer to the line of police, the protestors kneeled down and began to pray. The police asked them to turn around and stop marching. But the marchers refused.

Suddenly, tear gas burst into the air and “racism unleashed this brutality” onto the marchers, Webb-Christburg told The 19th. The dogs and horses began pushing their way into the crowd, trampling protestors “as if they weren’t human beings.”

Her eyes began to burn from the tear gas. She turned away and ran toward her home in the George Washington Carver projects. In the corner of her eye, she saw people running beside her, some falling to the ground and others being beaten by the police.

Webb-Christburg was 9 — the youngest of the protestors that day.

“The picture of Bloody Sunday has never left my heart, nor my mind,” she said.

Local police, state troopers and citizens attacked the protesters, and 58 people, including civil rights leader and future Rep. John Lewis, were treated for their injuries at a local hospital. Later that night, thousands of Americans across the country watched the footage on their home televisions, witnessing firsthand the violence that the protesters experienced. It was a pivotal event in the public perception of the civil rights movement, and five months later, on August 6, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law, prohibiting racial discrimination in voting.

From the end of Reconstruction until the Civil Rights Movement, Black people were largely disenfranchised and didn’t have the right to vote. Although Black men were granted the right to vote with the 15th Amendment in 1870 and Black women with the 19th Amendment in 1920, Ashley D. Farmer, a civil rights historian and professor at University of Texas at Austin, told The 19th that stipulations like the grandfather clause — a state law that restricted Black men from voting unless their male ancestors voted — poll taxes and literacy tests kept Black voters from exercising their civic duty.

“We should understand that Bloody Sunday was a culmination of a lot of different grassroots efforts to change that nearly 100-year history,” Farmer said. “It really was a monumental moment in terms of the bravery of people … and also in terms of what happened in response to people trying to execute their constitutional right.”

While many weren’t in the spotlight, Black women were the backbone of the civil rights movement: They fed protestors, planned meetings and worked behind the scenes to contribute to the fight to end Black voter suppression and other forms of discrimination. Decades later, their full contributions are still being acknowledged.

“You don’t get a Bloody Sunday, you don’t get such a march without the work of grassroots organizers, particularly Black women and particularly the Black women in the Dallas County Voters League,” Farmer said. “You may see the flashy protest, but below the surface is a strong collective of people, Black women usually, that are creating the networks, trust, community-building and organizational literacy for something [like this] to be able to take place.”

As young Black marchers traveled to Selma to see their way across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the women of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), a nonprofit advancing the quality of life for African-American women, opened their doors and offered hundreds a place to sleep while in the city.

Dorothy Height, the president of NCNW for 40 years and known as the “godmother of the civil rights movement,” implored local members of the Black women-led organization to not only provide housing for organizers but also partner with historically Black Divine Nine sororities like Delta Sigma Theta and Alpha Kappa Alpha to feed and protect Selma marchers from law enforcement.

Height’s work with NCNW continued throughout the civil rights movement as the organization assisted in organizing the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963, and she was the only woman sitting on stage while Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech.

Today, the Rev. Shavon Arline-Bradley, a Black woman, ordained minister and expert in diversity, equity and inclusion, serves as president and CEO of NCNW and sees her role as carrying on Height’s activism.

“The work we do today means everything to me. We are almost 90 years old and we continue the legacy of our longest-serving president, Dorothy Height, who really stood as the only woman in the civil rights space that represented the interest of Black women,” she said.

Since 1965, NCNW has been instrumental in commemorating Bloody Sunday. This year, Arline-Bradley will be in Selma to reenact moments where NCNW supported, fed and housed marchers. NCNW will also partner with Salute Selma, a nonprofit dedicated to continuing the work of the civil rights movement, to conduct an education advocacy forum on the ongoing fight for equality.

“NCNW has a strong history in this space and we look forward to commemorating Selma this year,” Arline-Bradley said.

For Celina Stewart, CEO of the League of Women Voters (LWV), the contributions that Black women made to demonstrations like the march on Bloody Sunday are undeniable. She pointed to activists like Diane Nash, a notable leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and one of the marchers that Sunday.

“She really transformed those tragedies into strategic action. She began envisioning the Selma marches as a way to continue to force national attention on both the racial violence but also the voting rights violations that were happening in Alabama,” Stewart said.

Nash had a persistent spirit and advocated for march strategies in Selma due to the high level of organizing that was already present there. She was soon able to convince prominent civil rights leaders like King to focus on Selma as a primary campaign site.

“Her story really reveals how women’s leadership often worked behind the scenes. So often we are not at the front. We are not on the stage, we are behind the curtain,” Stewart said. “For me, the most powerful lesson that came from Bloody Sunday is the importance of persistence. These women did not give up.”

Stewart also noted that many Black women who came before her were once excluded from the very organization she leads today.

“The league, founded in 1920, excluded Black women. My grandmother could become a member but she wasn’t allowed to do certain things,” Stewart said.

With a 105-year-old history of voting rights education, advocacy and grassroots action, LWV has strengthened its mission to empower women voters today by acknowledging the Black women who have set the groundwork for voting equality.

“Despite how critical we have seen Black women be, even at that time, to these movements, there was exclusion. There was a desire to have [Black women] in the back. So, that’s something we confront in our own history because that was a form of voter suppression,” Stewart said.

After Bloody Sunday, another pioneering Black woman, Constance Baker Motley, was part of the legal team that secured federal protection for future marches through the Williams vs. Wallace lawsuit.

Motley was the first female lawyer with the Legal Defense Fund (LDF), a law organization founded in 1940 focused on civil rights and racial justice. She also later became the first Black woman to serve as a United States federal judge.

According to LDF, Amelia Boynton Robinson was one of three plaintiffs listed in the Williams vs. Wallace case, which named then-Alabama Gov. George Wallace as a defendant. LDF had represented Boynton Robinson just two months prior to her involvement in the march in a voting-rights case against the state of Alabama.

“[Black women] are creating spaces that are needed for the types of organizing, for the types of fellowship, for the types of planning and strategy that are necessary to pull off something like the march from Montgomery to Selma, and to recover and heal after something like a Bloody Sunday,” said Ashton Wingate, manager of digital archives for the Legal Defense Fund.

For many years, LDF has also participated in the commemoration of the march by returning to Selma to conduct speeches and walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in honor of those they have represented.

Webb-Christburg’s experience on Bloody Sunday inspired her to continue as an activist in her community. She wrote a book, “Selma, Lord, Selma,” about her childhood and founded a youth development program to help students become leaders.

Leading up to the anniversary of Bloody Sunday each year, Webb-Christburg gives speeches and tells her story across the country. Every year on March 7, uplifted by the memory of the women who played a crucial role in organizing the protests, sit-ins and meetings of the civil rights movement, she crosses the Edmund Pettus Bridge in honor of Bloody Sunday and the fight for freedom.

“From year to year, it’s always mixed emotions when I cross that bridge,” she said. “I can’t help but to reflect on how far we’ve come. But yet, in such a time as this, we still have a long way to go.”