Pennsylvania Sen. Bob Casey Jr., considered one of the chamber’s leading champions of disability policy, conceded in his Senate race last night, ending the Democrat’s decades-long career in Congress. Republican Dave McCormick, a former hedge fund manager, won by less than 0.5 percent, a margin that had led to an automatic recount.

Casey was best known as a “mild mannered,” even “boring” moderate. (A Philadelphia Inquirer columnist once compared him to a bowl of oatmeal.) Less well known is that Casey was instrumental in passing multiple pieces of bipartisan legislation — an increasing rarity — to advance the rights and well-being of people with disabilities.

McCormick’s victory means that Republicans have won 53 seats in the Senate. While some disability policy priorities have historically been bipartisan, Republican opposition to the Affordable Care Act and support for cuts to Medicaid in 2017 led to an increasingly polarized legislative environment for disability advocates. Advocates worry that Republican control of all three branches of government may jeopardize some of the gains made by the disability rights movement.

Casey first became involved in disability policy work through his mentor, former Sen. Tom Harkin of Iowa, who co-authored the Americans with Disabilities Act. The landmark civil rights legislation established that people with disabilities are entitled to access society and to have protection from discrimination.

Harkin remembers introducing national disability leaders to Casey in 2013, after Harkin announced he would not seek a sixth term in office.

“They were all asking [Casey] if he would pick up and be their lead person in the Senate. And without hesitation, he said yes. He was honored to do so. It was wonderful. Ever since then he has been a real champion on disability rights issues,” Harkin said.

Casey does not have a personal connection to the disability community the way Harkin did — Harkin’s brother, Frank, was deaf, and that shaped his interest in disability rights. Harkin credits Casey’s dedication to disability rights to his deep sense of economic and social justice.

“He always had the right attitude — one I shared about the whole disability community. Too many people who are non-disabled approach the disability community out of a sense of pity or charity. Bob always looked upon it as, ‘How do we change the structure of society so that you can live your life, follow your dreams, do your job?’” Harkin said.

Casey sees his leadership in disability policy as a natural progression of his policy work.

“When I got to the Senate, some of the issues that I was focused on were issues relating to children, families and seniors. That naturally led me into disability work,” Casey told The 19th His constituents gave him extra reason to push, he said. “A lot of disability advocates and folks in Pennsylvania were asking me for help, and that naturally led me into more of a leadership role.”.

Over the course of his political career, Casey introduced dozens of bills to advance civil rights and quality of life for people with disabilities. The Achieving a Better Life Experience Act, or ABLE Act, was perhaps his signature achievement. The law, passed in 2014 with robust bipartisan support, allowed people who became disabled before age 26, and who rely on Supplemental Security Income (SSI), to save more than $2,000 without losing their benefits.

In many states, qualifying for SSI is a requirement to qualify for Medicaid. Medicaid is the primary provider of home care in the United States, and many disabled recipients rely on it to do things like get out of bed, eat and get dressed. ABLE accounts allow more disabled people to save for the future, buy a home and more, without worrying about losing the care and support they need to live their lives.

“We had Republicans and Democrats in the House working on it and the same in the Senate. Richard Burr and I, a Republican representing North Carolina, who just left the Senate a few years ago. He and I worked on it for years. It was great to have that kind of a bipartisan breakthrough where we were simply making a change to the tax law,” Casey said.

While Casey thinks of the legislation itself as simple, there was nothing simple about getting it passed.

“It took an awful lot of work over many years to pass it. Even though it had bipartisan support, we had to keep it in front of people. Often, even really good policy that has widespread support can drift in Washington, unless you have a constant drumbeat of advocacy,” he said.

In particular, he remembers the words of Sarah Wolff, one of his constituents and an advocate for the ABLE Act. Wolff has Down syndrome and was frustrated that she could not save money without losing in-home support she needed to live independently.

“Sarah said at that time, ‘we gotta keep pushing, we gotta get this done. We gotta stay pumped.’ You could pay some communications consultant a lot of money to come up with a two-word line like that. But she said, ‘Stay pumped. Stay pumped.’ And that meant ‘stay focused on getting this done.’ Just a few months later, it passed in December of 2014,” Casey said.

Casey also passed subsequent bipartisan legislation in 2022, the ABLE Age Adjustment Act, which extended ABLE account eligibility to people who acquired their disability before age 46. Most recently, Casey and Sen. Eric Schmitt, a Republican representing Missouri, introduced the Ensuring Nationwide Access to a Better Life Experience Act or ENABLE Act, which would further expand what ABLE accounts can do for disabled people and family caregivers. The bill was referred to the Senate finance committee in June.

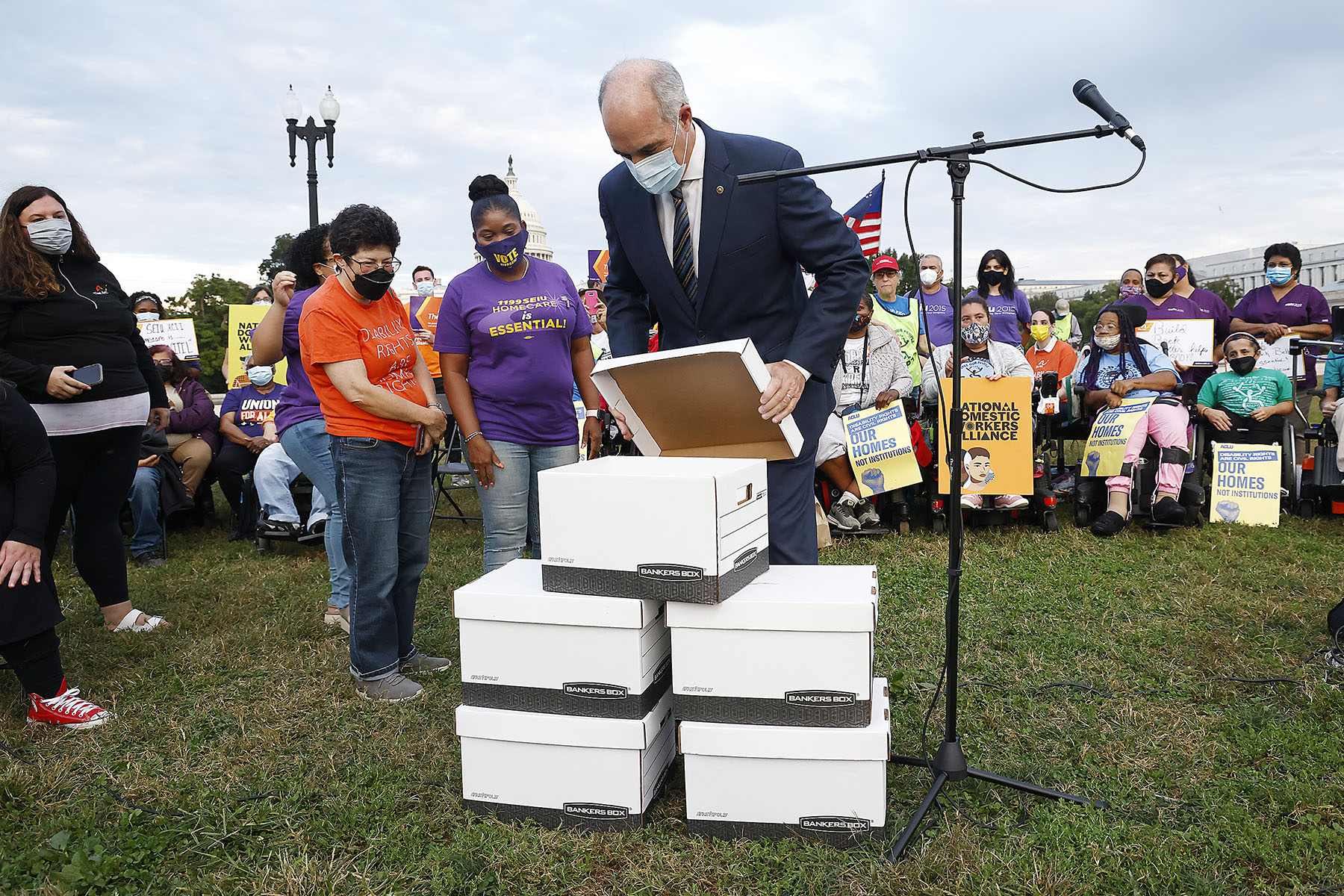

With Casey’s defeat, advocates in the disability community are mourning the loss of a longtime ally. Maria Town, president of the American Association of People with Disabilities, praised not only Casey’s dedication to disability policy priorities, but for his respect for community members, including herself. She recalled a 24-hour vigil in front of Congress that disability and labor advocates held to advocate for long-term care provisions in President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better Plan in 2021. Casey arrived to speak at the end of the vigil. Town was scheduled to introduce him.

“I wanted to appear very professional and competent. I was nervous. So what did I do? As soon as he came over, I just fell right on him,” Town told The 19th.

Town has cerebral palsy, which impacts her sense of balance. Falls are not uncommon for her. Casey’s response, however, was.

“He did not miss a beat. He didn’t freak out, which is what a lot of people do when I fall. Instead, he gave me the space I needed to articulate how I needed support to get back up. I think that really speaks to the way that he’s engaged with a lot of disability advocates and with a lot of disabled people. He doesn’t assume he knows what needs to happen. He listens,” Town said.

Town noted that Casey brought the same attitude when it came to policy work. This included efforts to push for regulatory changes from the executive branch during the Biden administration like improvements to web accessibility.

“I think he, his office and his staff have been great partners in listening to what our community needs and figuring out how to make those things possible,” she said.

President-elect Donald Trump has pledged not to cut Medicare or Social Security, but he has made no such promises about Medicaid. In 2017, he led the push to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, which entitles people with “pre-existing conditions,” including disabilities, to normal health insurance. This push was paired with drastic cuts to Medicaid and was vigorously opposed by disability advocates. Casey was a frequent presence at disability community events to defend the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid in 2017. Casey credits the disability community with saving the Affordable Care Act.

“What I remember most is those families [of disabled children] and people with disabilities making their case over and over again to members of the Senate from both parties. The Little Lobbyists and other groups were just everywhere. They kept coming back week after week, month after month. It taught me a lot about the power of advocacy and the power of real people to either make change or prevent bad policy from becoming enacted into law,” Casey said.

Trump and his allies have indicated they may try again. During the presidential debate in September, Trump said he had “concepts of a plan” to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. In October, Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson indicated he would be amenable to pursuing “massive” changes to health care. Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act may once again be on the chopping block during Trump’s second term.

McCormick, who will take Casey’s place next term, is a longtime opponent of the Affordable Care Act. During the 2022 Republican Senate primary race against Dr. Mehmet Oz, McCormick criticized Oz for being too supportive of the Affordable Care Act. It is unclear if he will also support cuts to Medicaid. In October, he told AARP that he supports expanded access to home care for older and disabled adults. Home care is primarily funded through Medicaid.

Theo Braddy, is a longtime constituent and has lived most of his life in Pennsylvania. He is also the President of the National Council on Independent Living, an umbrella organization for centers across the United States that provide peer-led, community-based services to people with disabilities. Braddy himself is disabled — when he was a teenager, he broke his neck in a football accident.

Braddy — who also worked alongside Casey’s father, former Governor Bob Casey Sr., on disability rights in the late ‘80s — was honored by Bob Casey Jr.’s office in 2022 alongside four other Black Pennsylvanian “trailblazers.” Braddy recalled being asked what could be done to improve the lives of people with disabilities.

“I said, ‘You’ve got to appoint people with lived experience, with disabilities, in order to not to create oppressive programs and services.’ Because they have that lived experience, they know what’s not necessary and what is necessary,” Braddy said.

A few months later, he found out he had been nominated to the National Council on Disability — an independent federal agency that advises the president on disability policy — in part because of his talk with Casey, who recommended him for the position

“He heard me. He listened to me that day and he took a step to change things. So many decision makers overlook multiply marginalized groups. They don’t listen. They do what they believe they need to do and not necessarily what needs to happen. In not one of my encounters with Casey, or any staff for that matter, have I ever been left with the feeling that he did not hear me. I’m going to miss that [if McCormack wins],” Braddy said.

There are other sitting senators who support disability policy priorities. Town pointed, in particular, to Democratic Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois and Republican Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana. But Casey will be missed.

“Senator Casey has done a lot to support the disability community in the federal policy arena. He has also done significant work to support disabled people in Pennsylvania and has really strong relationships with Pennsylvania-based disability advocates. I think that’s really important,” Town said.

What are Casey’s parting words to the disability community?

“It is important not to despair when it looks like majorities might be against you, or an administration might be contrary to what you believe in, either in disability policy, or more broadly. Just remember the recent examples of the power of advocacy and the results that can come because of that advocacy,” Casey said.