This piece was published in partnership with Them. Sign up for The Agenda, Them‘s news and politics newsletter, delivered to your inbox every Thursday.

A Supreme Court case that will decide whether Tennessee can continue to ban gender-affirming care for transgender youth could imperil the ability of all Americans to make decisions about their health care, experts say. The outcome depends on how far the court is willing to stretch its ruling that overturned federal abortion rights.

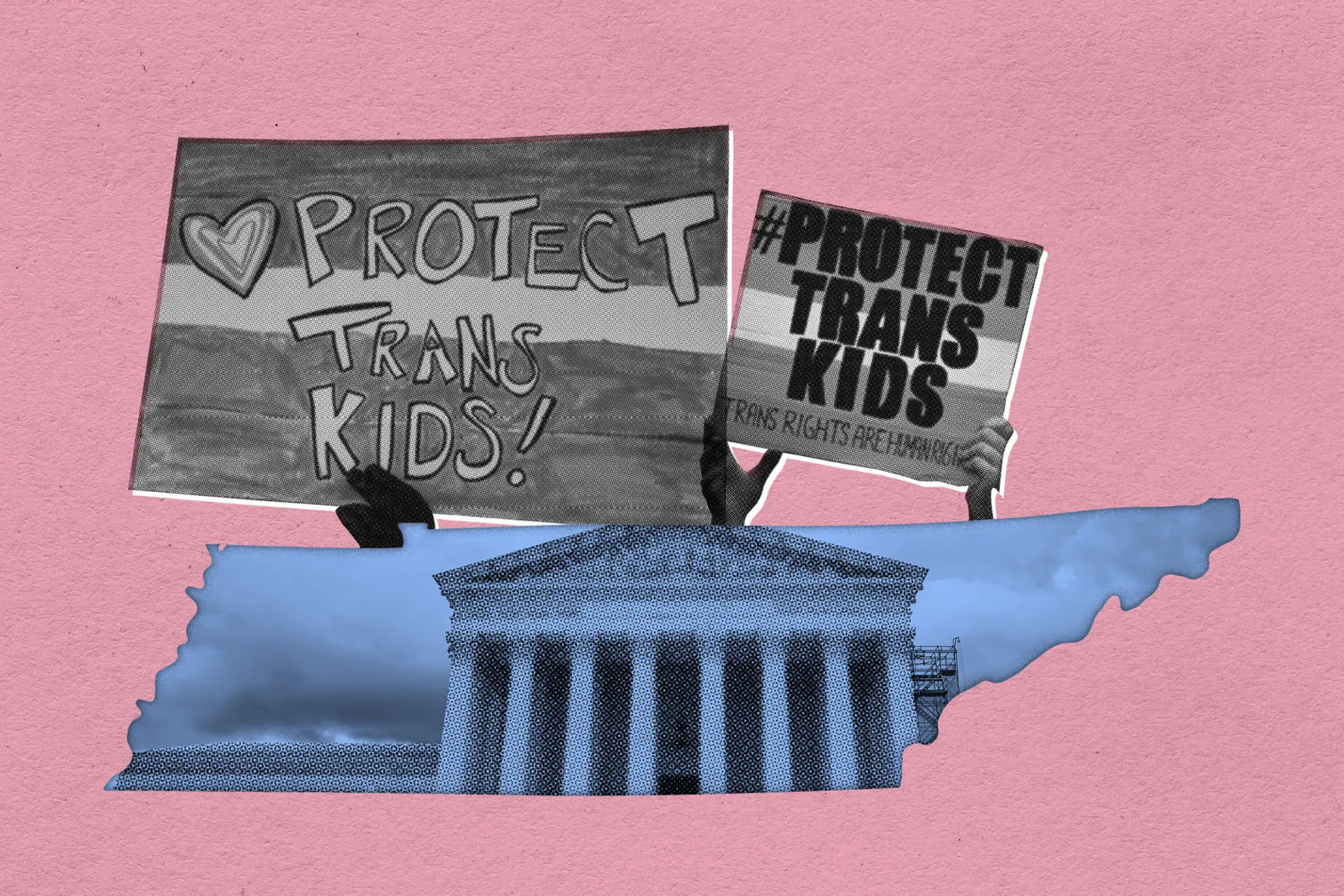

In United States v. Skrmetti, the court has agreed to take up the question of whether gender-affirming care bans for trans youth are unconstitutional, in response to the Biden administration petitioning on behalf of trans youth and their families in Tennessee — one of 26 states that has banned such care for minors. The outcome of the case will grant much-needed clarity in a political landscape that has thrown the lives of trans people across the country into turmoil, as hospitals turn patients away, pharmacies deny prescriptions and families travel hundreds of miles to find care.

But with the case set for oral arguments on December 4, the stakes are even higher than most Americans realize, legal and policy experts say. Tennessee has banned gender-affirming care, such as puberty blockers and hormone replacement therapy, for a specific demographic — trans youth — while allowing those same treatments for cisgender youth. If the Supreme Court allows the state to keep its ban in place, that could imperil everyone’s access to health care.

“What the state of Tennessee is arguing is really dangerous for any person who has any sort of medical condition,” said Ezra Young, a civil rights lawyer and constitutional scholar. Tennessee is dictating what medical treatments people should or should not be allowed to have, Young said; that goes well beyond states’ authority to regulate medicine, specifically because giving health care to trans people is not a public health concern.

“The state can make sure that the doctor you see has a medical degree and has an active medical license, for instance,” he said. “What the state can’t do is micromanage the medical decision-making of patients or doctors, and that’s for good reason. Bureaucrats or lawmakers aren’t medical experts.”

Yet in half of U.S. states, Republican lawmakers have banned or restricted medical care that many trans people need to live, over the protests of the American Medical Association, American Psychiatric Association and other leading medical groups. Federal judges have attempted to block these bans from taking hold, finding them to be likely unconstitutional. Appeals court judges have disagreed and overturned those decisions. Now, the Supreme Court will have the final say.

“If we don’t win here, it’s going to be open season on any health care related to transgender people,” said Shannon Minter, legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights. If the Supreme Court holds that banning gender-affirming care is not discriminatory, then trans people would no longer be protected under the Affordable Care Act, he said. States and private insurers would be able to exclude gender-affirming care from coverage plans.

“It would be devastating. I mean, absolutely catastrophic,” Minter said.

Ultimately, the outcome of this case will have a wider impact beyond gender-affirming care. A Supreme Court ruling endorsing Tennessee’s argument that the state can ban safe medical care — just because it disagrees with who that treatment is being given to — would enable the government to control people’s health decisions and enact other blatantly discriminatory policies, legal experts say.

“I think this case has bigger and broader implications than a lot of people realize, even frankly within the legal community,” said Michael Ulrich, an associate professor of health law, ethics and human rights at Boston University’s School of Public Health and School of Law. If the Supreme Court agrees with Tennessee’s ban, there’s nothing stopping states from banning or restricting other kinds of health care, he said — like what gets covered under Medicaid.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar’s office, representing the Biden administration, will split argument time before the Supreme Court with Chase Strangio, co-director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s LGBTQ & HIV Project.

The United States v. Skrmetti case is focused on whether Tennessee’s gender-affirming care ban violates the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex. The state insists that its ban has nothing to do with sex and that it does not target trans people. Instead, the law “sets age and use-based limits,” Tennessee’s attorney general argues. Minors can still access hormones and puberty blockers for medical purposes, as long as those treatments are not being used as part of a gender transition or to alleviate gender dysphoria. The state claims such a distinction is not based on sex because “neither boys nor girls can use these drugs for gender transition.”

To support this argument that the ban is not discriminatory, Tennessee is looking to the case that overturned federal abortion rights.

In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Supreme Court found that there is no constitutional right to an abortion in the United States. This ruling overturned Roe v. Wade, the landmark case that had guaranteed the right to an abortion since 1973. When writing the majority opinion in Dobbs, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito briefly addressed a theory that suggests abortion could be covered under the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. This idea is not part of Roe, or at issue in Dobbs, but was invoked in a separate “friend of the court” brief. Alito dismissed it, saying that state regulations on abortion do not discriminate based on sex.

“So that’s what the state of Tennessee is now latching on to, this passing reference, this brief statement in Dobbs, and they’re pinning their whole argument on it,” said Minter. “Everything hinges on it.”

In Dobbs, Alito wrote that abortion cannot be protected under the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, citing the arcane Geduldig v. Aiello — a case about pregnancy-related disability benefits — and Bray v. Alexandria Women’s Health Clinic, a case dealing with the rights of anti-abortion protesters. These rarely cited cases found that state regulations on abortion and pregnancy, or opposing abortion, is not sex discrimination. Tennessee is now using this framework to argue that “any disparate impact on transgender-identifying persons” caused by its law does not single trans people out for discrimination in ways covered by the 14th Amendment.

If the state’s gender-affirming care ban is found by the Supreme Court to be discriminatory under the 14th Amendment, it is subject to heightened scrutiny — a more rigorous review to determine whether a law is constitutional or not. In that scenario, Tennessee is more likely to lose.

Using abortion case law to support bans on gender-affirming care is especially dangerous, experts say. Tennessee is taking the Supreme Court’s own decision in Dobbs out of context, according to lawyers who have worked in LGBTQ+ rights cases for decades. And, if the justices read Tennessee’s law, it is obvious that banning gender-affirming care for trans people is discriminating based on sex, they say.

Only banning gender-affirming care for people who are transitioning is clearly a policy dividing people based on their sex characteristics, experts say — which should be apparent to the justices, even if they don’t fully understand what gender-affirming care is.

“It’s not about whether they understand or agree with the care,” Minter said. “All they have to do is read the language of these laws, which use the term sex over and over again.”

But Tennessee’s argument echoes circuit court decisions that have forced gender-affirming care bans to take hold across several states — thanks, in part, to Dobbs.

Last year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit allowed Kentucky and Tennessee to enforce their health care bans for trans youth. The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled via a three-judge panel that Alabama could enforce its gender-affirming care ban. Both circuit courts cited Dobbs, as well as Geduldig, to argue that these bans do not discriminate on the basis of sex, since laws restricting abortion don’t trigger heightened scrutiny.

To Polly Crozier, director of family advocacy at GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders, Tennessee’s arguments relying on Dobbs are just smoke and mirrors. And while it’s not surprising that Tennessee is doubling down on the approach that won in the 6th Circuit, she said, Dobbs cannot prop up this case.

“You cannot ignore the fact that this law is regulating medical care only for a particular group of people, transgender people, and it’s clearly discrimination based on sex,” she said, noting that the cases are fundamentally different. Dobbs dealt with whether substantive due process — meaning unenumerated rights in the Constitution — included the right to an abortion. Analyzing potential sex discrimination wasn’t involved.

What’s more, the question before the Supreme Court regarding Tennessee’s gender-affirming care ban is different from what the 6th Circuit took up last year. The initial case, brought by the American Civil Liberties Union and Lambda Legal, accused Tennessee of violating the 14th Amendment’s equal protection and due process clauses when the state banned gender-affirming care. Any consideration of due process is no longer before the court, since the Biden administration’s appeal for the Supreme Court to take up this case focused only on equal protection.

But, although the question before the court has become more specific, this ruling still has the potential to broadly set back LGBTQ+ rights.

Tennessee argues that the Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County, which found that employment discrimination against LGBTQ+ workers is sex-based discrimination prohibited under the Civil Rights Act, has nothing to do with this case. But going down this road leads to more questions, Ulrich said: Is discriminating due to sexual orientation also not considered sex-based discrimination?

“Then you can see just a proliferation of discriminatory laws that are coming out thereafter,” he said. “That’s a really dangerous proposition for the entire LGBTQ+ community and it’s setting us back significantly.”

Sruti Swaminathan, an ACLU staff attorney who has been counsel in this case from the beginning, said United States v. Skrmetti will test how far the Supreme Court is willing to stretch its Dobbs decision. They are well aware that the outcome of this case could curtail bodily autonomy for everyone. And taking this challenge before a conservative-majority Supreme Court has stoked fears among trans people of worst-case scenarios.

“We’re already at the place where half the country has banned this care. We need to not let the 6th Circuit decision stand idly and be utilized in the way it has,” Swaminathan said.

But Tennessee’s tactics, and the consequences that they could have during a time when laws targeting reproductive and transgender health care are proliferating, still worry them.

“I’m terrified. What we learned from Dobbs is that these attacks won’t stop with abortion,” Swaminathan said. “Banning abortion seems to be one pillar of an effort to write outdated gender norms into the law.”

Tennessee’s argument in this case illustrates a larger coordinated effort to attack abortion access alongside gender-affirming care, said Logan Casey, director of policy research at the Movement Advancement Project, a nonprofit that tracks LGBTQ+ legislation.

States across the country have attempted to define sex based on reproductive capacity at birth. These efforts open transgender people up to discrimination and ignore the realities of intersex people, as well as cisgender women with conditions like primary ovarian insufficiency. Proponents of gender-affirming care bans inaccurately portray the effects of hormone replacement therapy on trans people’s reproductive ability by conflating the treatment with sterilization.

This Supreme Court case exemplifies a much larger argument that’s been a through line across attacks on transgender care and trans issues across the country, Casey said: What is sex and who is protected when we think about that?

“Many of these state actors and politicians and extremists are clearly very invested in the concept of sex and defining sex in a very restricted and extraordinarily old-fashioned way that focuses only on people’s reproductive capacity, and then they use that argument in whatever context they can to advance the policies that would match that worldview,” he said.

From the Collection