When Jasmine Emery wasn’t driving the #400/405 bus, she’d use her short breaks to gingerly attach her breast pump under her uniform and hope passengers wouldn’t barge in or hear its suctioning over the hiss and clatter of metro Detroit.

The milk went into a cooler, tucked under a frozen water bottle. There was nowhere to clean her pump when she was done. It was 2021, and Emery was just back from maternity leave after the birth of her third child. The bus wasn’t an ideal place to pump, but it was the best she could do. What rights did she have anyway? she thought. What choice?

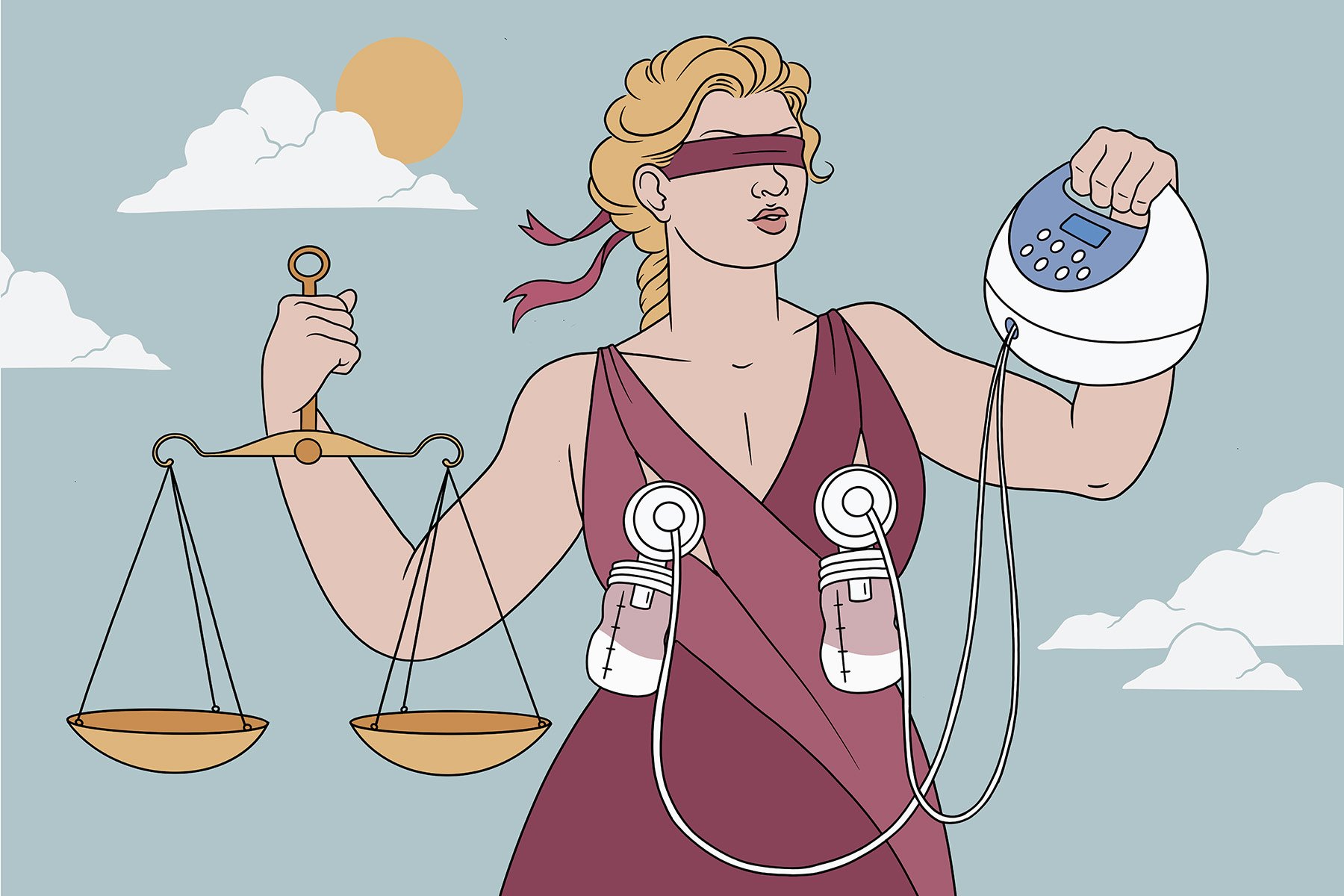

But by the time Emery returned to work in April 2024 after the birth of her fourth child, the world had changed. In December 2022, Congress passed a law called the PUMP Act with strong bipartisan support. It mandated that employers give workers adequate break time and a private space — preferably locked — to pump. It also gave workers a new and very powerful weapon: If their bosses didn’t comply, they could sue.

Yet Emery’s bosses, she recalls, just suggested she do the same thing she’d done in 2021: pump on the bus.

Figure it out, she said a supervisor told her. You’re not the first person to have a baby.

This time, Emery knew she could push for more. A friend had told her the new law could protect her, and a call to the Department of Labor confirmed it. “I told myself, ‘I’m not going through that again,’” Emery said. “I believe in breastfeeding. I promote breastfeeding. It’s my right and I want to exercise it at every point.”

For about a month, Emery and her employer, SMART Bus, went back and forth. First, she recalls, they offered to buy her a hands-free pump that she could use on the bus while she wasn’t driving, but pumping in a public space with nine cameras watching her every move robbed her of her privacy. Next, they put her up in a room at the bus terminal that had no lock — and on the first day a male coworker burst in when she was pumping and exposed, she said. Emery suggested stopping to pump at a hospital on her route, but she said she struggled to get access to a private room there, too. Her bosses suggested the state fairgrounds, but her only option there was to pump inside a grimey Porta John.

-

Previous Coverage:

Every delay only added to her stress. On top of the anxiety and exhaustion that accompanies having a newborn, Emery now had to worry about how she’d even feed him.

“It affected my quality of life, my happiness, my sleep,” Emery said, recalling that time through tears. “It hurts emotionally. I would have never thought a company I gave over four years to would do me as such.”

Exasperated, this May, Emery sued.

Her case, filed in U.S. district court in Michigan, is one of a swelling number of lawsuits, all filed this year, against employers who are allegedly failing to provide nursing mothers with the time or a space to pump. About a half dozen collective and class action lawsuits have been filed against large national employers, like the U.S. Postal Service, and prominent retailers and restaurants, including McDonald’s, Starbucks and Nike.

In the other cases, workers say that they faced similar problems, including insufficient — or non-existent — pump breaks and access only to public spaces where they were often interrupted by coworkers. Workers say they are being instructed to pump in their cars, in bathrooms or in unlocked managers’ offices.

In her suit, Emery is asking for damages to compensate her for the distress she experienced and lost wages. Most of the others are also asking for damages or injunctions for immediate relief.

SMART Bus spokesperson Katie A. Lauderbaugh declined to comment on the specifics of Emery’s case, citing pending litigation, but told the 19th that “SMART is dedicated to creating a supportive and inclusive workplace for all our employees, including new mothers. We strive to continually improve our workplace environment, and we take employee accommodations seriously.”

SMART Bus has denied all of Emery’s allegations, saying in court documents that it “worked diligently and spent many hours in its attempt to locate appropriate locations for Plaintiff to pump along her bus route.” The company says Emery asked for an electrical outlet for her pump the day before she returned to work, and in response they offered to buy her a hands-free pump of her choice, something the company argues satisfied her request. SMART Bus wrote that it provided a “temporary solution until a permanent solution could be found” by allowing her to pump in the unlocked room at the terminal. It was only after the hands-free pump was purchased that Emery provided the required 10-day notice that her employer comply with the PUMP Act, the company argues.

SMART Bus’ court filing also details its efforts to contact the local hospital and the university on Emery’s route to secure a lactation space. The company contends it was not aware until later that Emery had struggled to pump in those locations.

This complex debate between Emery and her employer illustrates a thorny problem: Workers who choose to pump need support from their workplaces in order to do it, and while the law requires that companies work to accommodate them, it’s not always easy. Some businesses that are used to functioning with limited staff every shift or within a small footprint may face more barriers to meet the requirement.

All of that means that parents like Jasmine Emery end up struggling to pump, mid-shift, from the driver’s seat of a bus.

Employers have actually been required to offer workers a space and time to pump for the last 14 years. But the law protecting that right, enacted in 2010 and called the Break Time for Working Mothers Law, had no teeth. There were limited ways to enforce it and no option to sue — so many of its provisions went ignored.

The PUMP Act expanded protections to 9 million workers who had been exempt from the original law and added the provision that allows workers to seek restitution.

Some states, including California and Washington, already had their own laws covering lactating people at work — and some go further than the federal law with additional coverage, such as requiring more employers to comply, or more rules for what needs to be in lactation spaces. But the new law expanded protections across the county; state laws that have more protections take precedence over the national law. The recent spate of lawsuits includes ones filed in both state and federal courts.

“The fact that we are seeing these lawsuits now is evidence that we needed the PUMP Act,” said Liz Morris, the deputy director of the Center for WorkLife Law, which helped draft the model legislation the federal law is based on. “Large companies should have policies and practices in place the same way they do when someone needs time off under the [Family and Medical Leave Act] because someone had a baby.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends breastfeeding for the first year of a child’s life, a standard that is difficult to meet in the United States because postpartum workplace protections are very limited. The U.S. is one of only a handful of nations that does not guarantee workers the right to paid time off after the birth of a child. (The FMLA only guarantees 12 weeks of unpaid leave.) About 95 percent of the lowest-paid workers in the country don’t have access to any paid leave at all. Without workplace protections for pumping, only about half of nursing parents are still breastfeeding their children at the six-month mark, according to 2019 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To maintain their milk supply, parents need to be able to pump about every two to four hours on the same schedule that they would nurse their newborns. Go too long without pumping, and they risk their breasts painfully swelling with milk, which could lead to infections and other serious health problems. In the long-term, both issues can cut how much milk their body produces.

How effectively parents who wish to breastfeed are able to do so is directly linked to their wellbeing in the tumultuous months after welcoming a newborn. Providing support in the workplace can help parents adjust back to the workforce while also serving the needs of their children.

Since the passage of the PUMP Act, employers are proactively responding to the needs of workers in many instances, said Elizabeth Gedmark, the vice president of A Better Balance, the lead advocacy organization that pushed for the PUMP Act. “There are employers who, because of the new federal law, are updating their policies and procedures,” Gedmark said.

Others, she said, have been increasingly receptive to requests from their employees. “We are hearing from workers who may be scared to go into a conversation. We educate them about the law, and then [they] are able to have those conversations and are not met with resistance,” she said.

Overall, advocates said, the companies that have adapted the most quickly offer white-collar jobs and office-based work. In these spaces, providing accommodation means setting aside an already-existing space for pumping, often an office or conference room. Break time isn’t a challenge when workers already have flexible schedules, and potentially options to work remotely.

But low-wage workers in retail and customer service jobs, most of whom are women of color, face the highest barriers. They may be in jobs that require them to be outdoors, or work in tight spaces without private offices or locks on doors. Hourly employees often work jobs with high turnover, where schedules are already inflexible. That makes asking for the accommodation a barrier in itself, especially when employers are known to retaliate or fire workers in favor of someone else who doesn’t need adjustments.

Pumping itself requires very high standards of cleanliness, because infants’ immune systems are still developing. Bottles and pump parts should be cleaned immediately after use and are typically sanitized daily. That is much easier to do in an office with private spaces, and harder at a fast food restaurant or strip mall store where the only available space may be the bathroom.

“There really is a racial justice aspect here,” Gedmark said. “These issues disproportionately affect low-wage women of color who’ve been pushed into these rigid and inflexible jobs because of sexism and racism.”

It’s probably no surprise, then, that after the passage of the PUMP Act, calls to attorneys and advocates rose, including to the hotlines at A Better Balance and the Center for WorkLife Law. Workers wanted to ensure that they could exercise this new protection.

For years, these two nonprofits have fielded dozens of calls from workers wondering what protections they can access at work. Morris has been closely following the cases, and has been in touch with the attorneys on some, she said. Often, employees already had ideas about how their workplaces could comply with the law, Gedmark added. Those solutions could be something as simple as a lock on a door, or making a manager’s office available.

Morris has worked with employers that have gotten creative. One agricultural employer created a pop-up tent with a chair, a desk and an extension cord that helped solve the issue for farmworkers. A bus company converted an unused Porta Potty shell into a lactation space and placed it along the route for its workers. Others have bought “pods” where people can pump or breastfeed privately.

“We have heard from workers in essentially all industries that their employer doesn’t know how to comply and says it’s not possible,” Morris said. “There is always some solution available — you may have to be more creative.”

In California, attorney Michael Morrison filed several class action lawsuits this year against major employers, including Nike and Starbucks, under the state’s version of the PUMP Act. The implementation of the national law has thrust the issue back into the spotlight, Morrison said, and encouraged employees to come forward.

According to the Starbucks suit, plaintiff Luz Iraheta, a shift lead supervisor at two stores in Los Angeles, was routinely denied permission to pump at a time other than her meal and rest periods, leading her to miss several pumping sessions a week. Sometimes, milk would soak through her shirt, she alleges in the complaint, and she had to pump in a back room behind a curtain. “At times, other male employees could see behind the curtain, and would stare,” the lawsuit alleges, and Iraheta had to give up pumping as a result.

In the Nike case, plaintiff Fantasia McDonald, a department manager at a Nike Factory Outlet Store in Folsom, California, said she was forced to drive 10 minutes to a friend’s house to pump during her lunch break because there was nowhere for her to do it privately in the store. After her milk supply dwindled, McDonald said, she stopped breastfeeding sooner than she wished to.

In their case against the U.S. Postal Service, three plaintiffs allege that their only options were to pump in a breakroom or a mail truck. And in the McDonald’s suit, a manager alleges that she was told to pump in a back office that didn’t have a door, so people walked in all the time. When she was the only manager on shift, she couldn’t take a break to pump at all.

USPS denied the allegations against it in court documents, saying the plaintiffs pumped in either a break room or a mail truck because they chose to. USPS declined to comment on the specifics to The 19th. Starbucks also declined to comment on pending litigation, and has not yet filed a response in court, but wrote in a statement to The 19th that the company cares “deeply about the experience every partner has while wearing the green apron.” Nike and McDonald’s did not respond to the 19th’s request for interviews and neither has filed a response in court to the lawsuits against them.

Morrison said employers often convey the idea that pumping isn’t something companies should get involved in. “It’s almost like they consider it a personal problem, something that should be handled in private, something that should be managed outside the context of the workplace,” he said.

A lack of accommodation for parents in the workforce can affect them financially and professionally, Morrison said: “Women who have to make that choice might stop working and lose their place in line, and they fall behind in salary and promotional opportunities.”

Those gaps in employment follow people their entire lives. They lead to lower overall pay, driving a bigger wedge between the median pay for men and women. The pay gaps between men and women can be largely attributed to parenthood — they only really start to emerge for women when they have children.

While women experience a motherhood penalty, men experience the opposite phenomenon: They are typically paid more when they have kids, what is known as the fatherhood bonus. Employers, whether subconsciously or not, often believe fathers are typically breadwinners and need more money to support their families.

Rob Howard, an attorney with Cunningham Dalman who is representing Emery in her case against SMART Bus, as well as another mother in a case against a local bar, said the response from employers has revealed a larger ignorance about breastfeeding.

“Employers aren’t aware of their obligations, and frankly, a lot of these businesses, if you get a male-dominated workforce, they may not understand what’s the big deal,” he said. Like: Just go over there and do it.

While some of the lawsuits suggest simple changes like locks for doors, larger-scale solutions, such as portable lactation pods from brands like Mamava, have been growing in popularity. The smallest version of the Mamava pod resembles a wooden wardrobe: It’s a bit over 7.5 feet tall, with an oak finish and an app-activated lock on the outside. Inside, a 4-by-4 foot space houses a desk, a chair, an outlet, a mirror and a fan for ventilation. Since 2015, Mamava’s pods have been placed in more than 750 sites, including stadiums, airports, hospitals and military bases.

Sascha Mayer, Mamava’s co-founder and chief experience officer, said inquiries have shot up since the PUMP Act was passed, but it hasn’t always translated to new business. The pods cost about $10,000 each, or less if employers buy a large quantity of them for multiple sites.

“I think it is a cost issue — but I honestly think it’s just a design within their space. They just cannot figure out within those small footprints how to make this happen. My guess is maybe they’re waiting for the problem to go away,” Mayer said. “It’s interesting to think that the potential of settling a lawsuit would be less expensive than a more broad solve. Perhaps it’s just buying time.”

In recent months, Mamava has been working on piloting a standalone version of its app-activated lock that it could sell to businesses that just need to turn an existing space into a lactation room. The prototype is currently being tested in 40 sites.

-

Read Next:

Mayer started working on the pods because she recognized that a human function as essential to life as breastfeeding lacked design solutions in public spaces. And for Mayer, “design connotes values.”

Gedmark has been thinking of it similarly. Law and policy can drive cultural change. Just the simple act of putting up a sign at a job site that says “Lactation Room” — one that employees will see often and come to expect as a normal part of the workplace — can change how people think about pumping, even if they’ll never need the accommodation themselves, Gedmark said.

“What is way too often an activity that is rendered invisible will no longer be invisible,” Gedmark said.

Emery’s lawsuit against SMART Bus is still ongoing, but about a week after she filed, the company changed her schedule so that she would have two breaks to pump in a private office — with a lock — at the bus terminal.

SMART Bus, via court documents, holds that it consistently attempted to accommodate Emery, and argues that she still went forward with the suit even though the company altered her schedule with additional break times and offered private spaces to pump.

But Howard, Emery’s attorney, disagrees. He said he’s working to secure damages for the time during which she was not accommodated.

Emery feels damages were done to her health — and to her son’s health. Her milk supply plummeted, and she felt uncertainty and mental anguish during her first month back at work postpartum. She started buying formula to supplement her son’s meals. There were days that she didn’t even have the energy to feed her baby. She couldn’t get up from bed to brush her toddler’s teeth.

“I’m trying to fight for myself,” she said of her decision to file her suit. But she wishes workers didn’t have to fight so hard with their employers: “I need back up.”