The morning of February 4, 2007, started off like any other for 25-year-old Lashanda Salinas. She got up and made the 20-minute commute to her job as a front desk clerk at a Nashville hotel where she greeted guests and checked them in.

Hours later, her life changed. Salinas was speaking with a customer when two police officers walked into the hotel lobby.

“They said that they were looking for Lashanda Salinas,” she told The 19th. At the time, her father was hospitalized with brain cancer. She initially feared he had died. “It was the type of feeling where your stomach goes up into your heart,” she said. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, this is it’. But it was something totally different.”

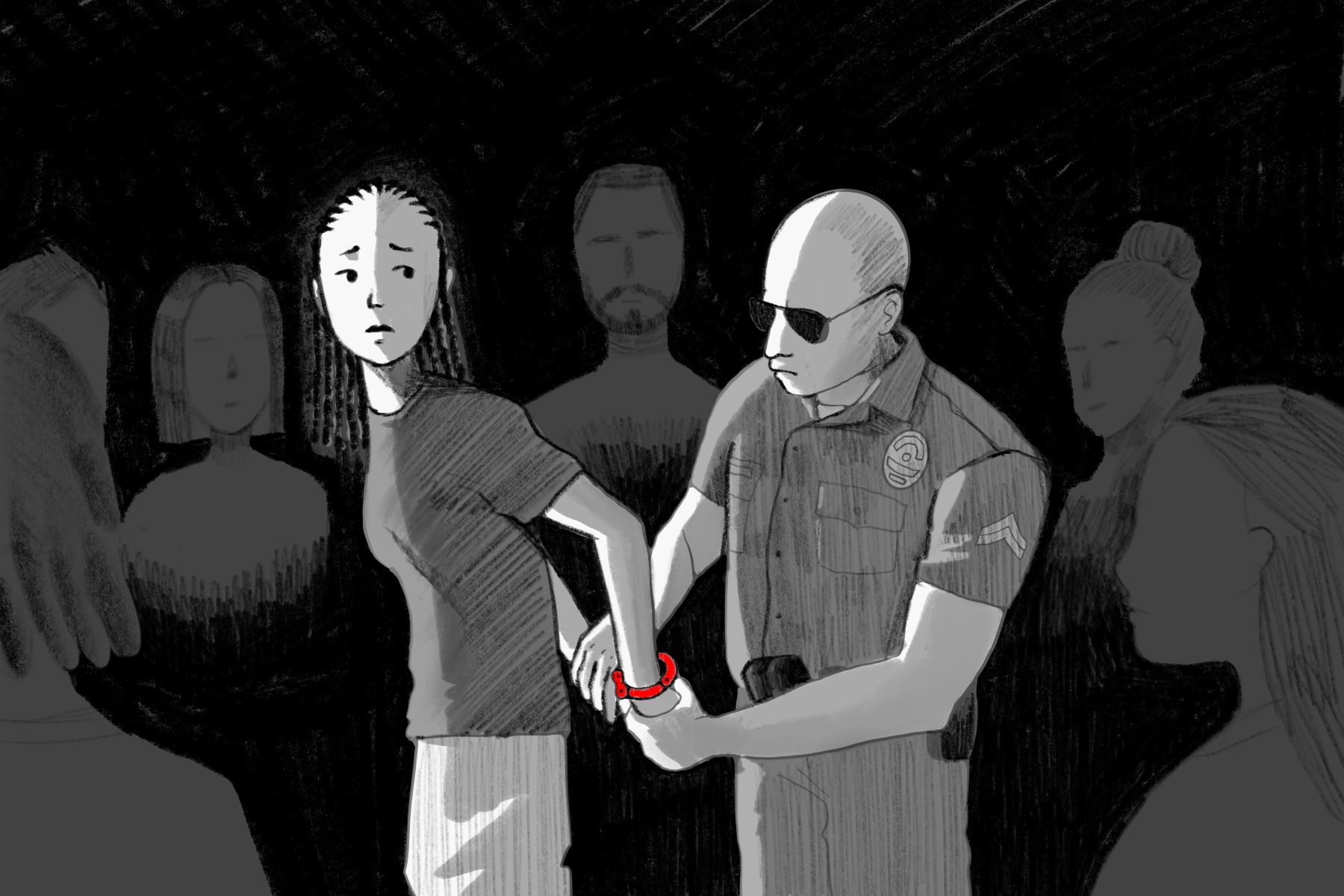

The officers informed Salinas they had a warrant for her arrest. Her ex-boyfriend had filed a report alleging that Salinas exposed him to HIV without sharing that she is positive for the virus. She was arrested and detained on a $100,000 bond for “criminal exposure to HIV,” a class C felony in Tennessee that is punishable by three to 15 years in prison and up to $10,000 in fines.

Salinas, who maintains that her ex’s allegation is false, agreed to a plea deal that gave her three years probation. She was released from custody on March 26. Her father died while she was incarcerated.

Salinas later learned that in addition to a felony conviction, she also had to join Tennessee’s sex offender registry, a reality that affected every aspect of her life, she said.

Seventeen years later, Tennessee is facing mounting pressure and two federal lawsuits calling for reform to its HIV criminalization laws. The attention on Tennessee underscores a nationwide effort. Thirty-four states have laws that criminalize people living with HIV in some capacity —policies that largely arose in the 1980s and ‘90s, driven by fear, homophobia and a lack of medical answers. But significant advancements in HIV treatment have drastically changed a person’s health outlook. Over the years, critics say, these laws have become another tool to criminalize Black people, LGBTQ+ people and sex workers, which are groups that already face discrimination in public health care and law enforcement.

“It would be healthy for folks to realize that criminalization is not an effective public health response to these types of public health threats,” said Michael Elizabeth, the public health policy strategist at Equality Federation. “Our response to HIV can oftentimes be from a place of fear, as opposed to a place of actually providing public health solutions to reduce the transmission rates within our communities.”

The first confirmed cases of AIDS in the United States occurred among a group of queer men in Los Angeles in 1981. The rapid spread among other gay and bisexual men fueled existing homophobia, deepening the marginalization of LGBTQ+ people.

With little medical research or treatment options for patients, contracting HIV was a death sentence for many. In 1990, Congress passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act, named after a teenager who was diagnosed with HIV in 1984 after receiving a blood transfusion. The Ryan White Act created one of the largest federal programs to provide funding for HIV care and treatment efforts.

But the legislation also made federal funds contingent on states establishing a legal process “to prosecute any HIV infected individual who knowingly and intentionally exposes a nonconsenting individual to HIV.”

This sparked a wave of HIV criminalization laws, many of which remain in place today.

The difference between today and 1990, however, is that HIV is now much more manageable. With modern treatments, a person living with HIV has a similar life expectancy as someone who is HIV-negative. Most people taking daily HIV treatment will see undetectable viral levels within six months, meaning they will not transmit the virus, according to the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control.

Still, the stigma against HIV persists both socially and legally.

As of December 2023, 37 states had a criminal law related to HIV or sexually transmitted disease status, according to the CDC.

“HIV criminalization is not a red state or a blue state issue; it’s not a big state or small state issue. We see criminalization across the United States,” said Nathan Cisneros, the HIV criminalization project director for UCLA School of Law’s Williams Institute.

Generally state policies have at least one of three focuses, Cisneros said. One aspect is nondisclosure, or neglecting to share HIV-positive status before engaging in sex or sharing contaminated needles for drugs.

Another is exposure, which involves potentially exposing the virus to someone through sex, blood donations or other nonsexual contact. Though saliva is specifically noted in some legislation, public health experts confirm that the virus cannot be transmitted through spit. The criminal punishment may be worse for exposing a member of law enforcement.

A third focus is enhanced criminal penalties for sex workers who are HIV positive. In most cases actually transmitting the virus to another person is not required to face criminal action.

In Washington state, for example, prior to 2020 exposing someone to HIV was a class A felony — a categorization reserved for the most serious crimes. Now, “intentional transmission of HIV” has been reduced to a misdemeanor. How they prove someone’s intent to transmit is not clear.

Among advocates for people living with HIV, Tennessee is known as one of the harshest states. It has two HIV criminalization policies: “aggravated prostitution” is a felony for someone engaging in sex work while knowing they are HIV-positive. Criminal exposure is a separate felony charge for sexual and nonsexual contact that could lead to HIV exposure.

Tennessee, Louisiana, Ohio and South Dakota and also the only four states where those convicted of an HIV crime may not only face prison time, but are required to join a sex offender registry.

When Salinas decided to take a plea deal for her criminal exposure charge, she had no idea it would add her name to the state’s sex offender registry.

“I found out that I had to register as a sex offender when I started my new job after I got out of jail. My probation officer called and told me that I had 24 hours to go register as a sex offender,” Salinas said. “I was pretty angry because I’m thinking, ‘My charge has nothing to do with a child. So, why am I on here with people that have molested and touched a child?’”

Back when Salinas was convicted, criminal exposure to HIV was classified as a violent sexual offense in Tennessee, which meant that Salinas could not live within 1,000 feet of a school, child care facility, public park, playground, recreation center or public athletic field. She was also generally restricted from being in the vicinity of children, though her conviction did not involve harm to a child.

The painstaking process of timing her grocery store runs so she could avoid children or measuring the distance from her home to the nearest school in order to comply with the law was one source of stress and shame for Salinas. But the isolation from her family took the biggest toll: 16 years of missed family holiday dinners and birthdays. She was forced to hear stories about her young cousins growing older without the chance to see them herself.

Like Salinas, Michelle Anderson, 38, lost time with family.

“People have to do this daily for years, where you can’t be around family like you want to, not only because of your HIV status but because the law says I can’t,” Anderson told The 19th. “Those little things that a lot of people do — that they take for granted, those are taken away from me by this law.”

Anderson, a Black trans woman living in Memphis, was arrested in October 2010 for prostitution and later charged with aggravated prostitution when her health records revealed she was HIV positive. Sex work was necessary for Anderson’s survival, she said. She had difficulty finding stable employment, something she said is a common concern for trans women, especially in the South.

With a felony conviction and her name on the sex offender registry, finding housing and employment became even more difficult. Though Anderson was eventually able to secure both, she depleted her savings paying the fees for rejected housing applications.

Salinas and Anderson reflect the populations most affected by HIV criminalization policies. Since 2016, the Williams Institute has published reports for individual states assessing their HIV laws. In report after report from around the country, Black people and sex workers are disproportionately punished.

A 2022 report on Tennessee by the Williams Institute examined 154 cases of people put on the state sexual offender registry for HIV-related crimes since 1993. Women represented 46 percent of the HIV registrants, though women accounted for 26 percent of people living with HIV statewide. Black people represented 75 percent of the HIV registrants, but made up 56 percent of those living with HIV throughout the state.

These figures cannot be divorced from the larger socio-political systems that already over criminalize Black and queer people, said S. Mandisa Moore-O’Neal, executive director of the Center for HIV Law and Policy.

“We need to keep in mind the inherent anti-Blackness of criminalization that has played out in the U.S.,” Moore-O’Neal said. “And when I say Blackness, I don’t just mean Black people. I also mean those in closest proximity to Black people. So, sex workers across race, queer people across race, but especially Black queer people, trans people across race, but especially Black trans people.”

In recent years, Tennessee and other states have seen growing demands to decriminalize their laws. Since 2014, at least 13 states have modernized or repealed their HIV laws, according to the CDC. Legislatures in Oklahoma and Maryland are currently considering similar changes as well.

In Tennessee, Salinas and Anderson are both part of a network of people pushing for change. A large part of the work advocating for reform is public education. Many people — including state legislators — know very little about HIV-related crime laws or how modern treatment options have drastically improved public health outcomes, advocates told The 19th.

While Tennessee’s conservative legislature has been slow to act, progress is happening, advocates said. Last June, Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee signed a bill that removed the sex offender registry requirement for criminal exposure to HIV. The requirement remains for aggravated prostitution convictions, meaning Salinas was able to request for her name to be removed from the registry, but Anderson could not.

Anderson is now one of five plaintiffs in a federal lawsuit currently challenging the state’s aggravated prostitution law. Filed by the American Civil Liberties Union, the ACLU of Tennessee and the Transgender Law Center in October, the complaint claims that the law violates the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which protects people living with HIV from discrimination. Last month, the Department of Justice also sued the state of Tennessee for allegedly violating the ADA.

Salinas continues to raise awareness about the importance of this issue and said she is relieved to no longer be listed as a sex offender. In August she was present for the birth of a new baby cousin, and in November she celebrated Thanksgiving with her family for the first time in more than a decade.

“Recently I rode with one of the ladies from my church and she had her grandson with her. To see his little hand hold my hand as we crossed the street, that was so magical and a long time coming,” Salinas said. “I love kids, and just to be able to be around a child, that is the most loving and amazing thing. I missed out on that for 16 years.”