At The 19th, we’re committed to publishing journalism that you can trust throughout the critical moments that shape our democracy and our lives. Show your support during our Fall Member Drive, and your donation will be matched. Double your gift today.

Sarah McBride is putting together the pieces of a successful congressional campaign: She’s leading across several polls, has the backing of key advocacy groups and members of her state’s political establishment, and just announced robust fundraising numbers. All that could add up to a win in the race for Delaware’s at-large House seat — making her the first ever transgender member of Congress.

The chance for McBride to make history, again, means facing the same question that she has spent most of her political career answering: Are the voters ready?

“People asked that question when I ran for the state Senate, and we proved them wrong. With people’s continued support, I’m optimistic we’ll prove those naysayers and those cynical political observers wrong once again,” she said.

McBride has already raised $1 million for the race, according to internal campaign documentation viewed by The 19th. Those funds are being raised well before the Democratic primary next September, which is likely to preview the real outcome of the race for a seat that has been held by Democrats since 2010.

For McBride’s campaign, reaching the $1 million mark so quickly is a retort to those who question whether voters will elect a politically experienced trans person to public office. It’s also a necessity — part of preparing for potential political attacks from Republicans during an era of super-charged anti-trans rhetoric.

“At the end of the day, while we’re energized and empowered by the support that has come in, we are trying to do something that has never been done before. And there is a reason for that. That is because it is really hard,” McBride said in an interview. Part of the challenge is overcoming cynicism and fear — and overcoming that recurring question.

Before the recent historic wins by trans elected officials in statehouses, before trans rights were a mainstream topic of news coverage, and before she was sworn in as the country’s first openly transgender state senator in 2021, McBride already felt that people were ready to support transgender political candidates.

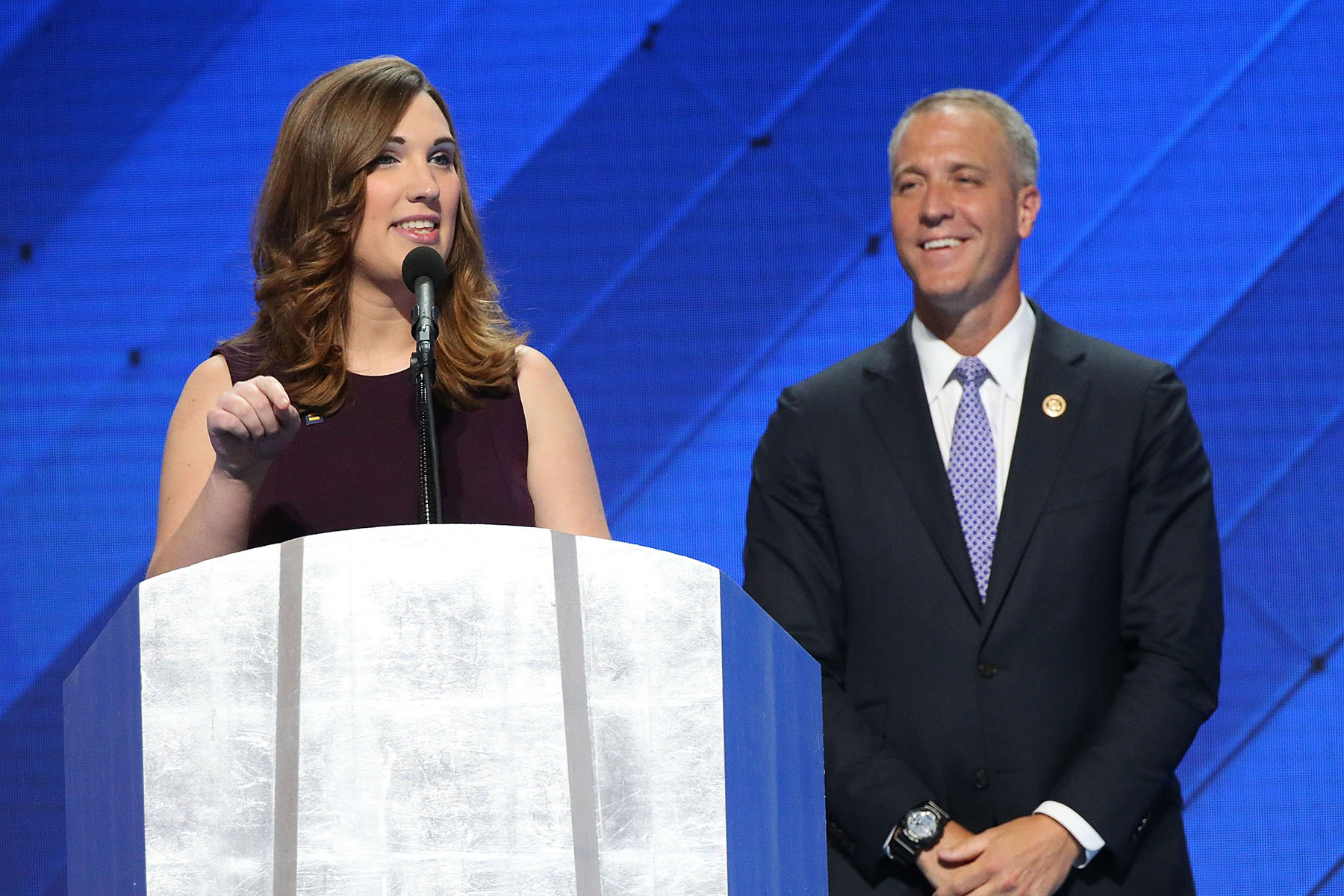

In November 2016, McBride — with experience already as a political advocate, a White House intern, staffer in the Delaware attorney general’s office and speaker at the Democratic National Convention — sat down to lunch with professors working on a study about public opinion toward transgender candidates. She had agreed to speak in one of their classes that week.

The study, with data gathered in 2015 and ultimately published in 2018, asked Democrats and Republicans whether they would support trans candidates in their own party. Voters reported overwhelming opposition. But they were asked about hypothetical candidates, with no real context about them beyond the fact that they were transgender.

That’s not how politics in the real world works, said Dannagal Young, one of the researchers of the study who met with McBride and a professor at the University of Delaware. That has become increasingly obvious as more transgender candidates win elections. It’s also something that McBride voiced during that lunch in 2016.

-

Read Next:

“What I loved about her, was she was like, ‘I think it would be different if it were an actual person.’ She just didn’t buy the idea that people would penalize someone specific — well, her. I appreciated that in the moment. And I think that what we’ve seen so far is that she’s right,” Young said.

Young, who teaches communications and political science, sees McBride as a clear example of how research on public opinion toward transgender candidates differs from reality. When actual trans candidates run for office, they come with rich biographies, voting histories and policy profiles that shape public views, she said.

“I think the reason that it is so notable with Senator McBride is that when you look at her biography … her public service predates her having come out publicly as transgender,” she said.

McBride was involved in politics from a young age, but the work she did before coming out was still guided, in part, by her identity, which she had known since she was at least 10 years old. She worked to support LGBTQ+ rights as a young person, even as she felt that her political future and her identity were mutually exclusive.

That work was a kind of solace — and also, a justification. For a long time, McBride believed that she needed to hide her gender identity or else her world would come crashing down. But if she could do enough to make it so that other people could be themselves, then maybe it would be worth it.

McBride detailed this journey in her 2018 memoir, “Tomorrow Will Be Different,” for which now-President Joe Biden wrote the foreword. At 18 and 19, she would repeat the same argument to herself: “Maybe I don’t have to live my truth if I can spend my life making the world a little fairer, if I can have a hand in making more space for other people — and future generations — to live their lives more fully.”

That changed in college. In April 2012, she shared her gender identity on Facebook — and later in an op-ed in the student newspaper, as American University’s departing student body president.

McBride later told her alma mater: “For me, having one more day pass by where I wasn’t living my true self seemed like such a wasted opportunity, such a wasted life.”

Since then, McBride’s political career has taken off — and that ascension has been intertwined with her gender identity, with showing people how the political is also personal.

-

Read Next:

McBride’s campaign priorities include policies like affordable child care, improving the cost of living, abortion rights, gun safety and expanding health care access — similar to many other progressive Democrats. Most of her day-to-day conversations with voters are about these issues. But in this current political moment, her campaign represents much more for families of transgender youth.

At least weekly, she’ll have two to three conversations on the campaign trail with parents of transgender youth, McBride said. Parents will hug her and say that her campaign means so much to their families. To her, it reinforces the responsibility that she has. If she wins, that will be a potentially life-affirming message to transgender people in Delaware and across the country, she said — and that she’s not just running to make history, she’s running to make a difference for those families.

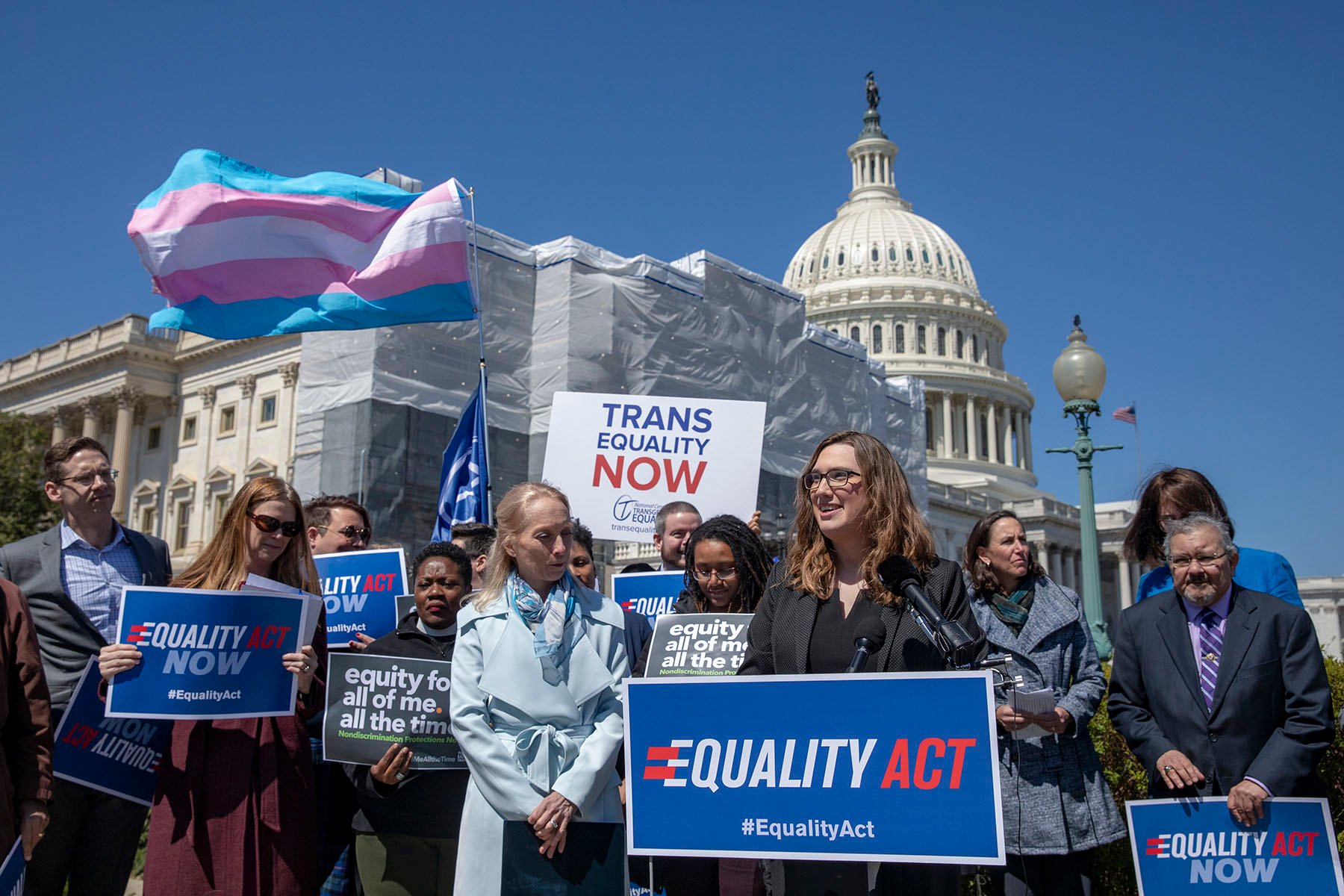

McBride, who’s now 33 years old, has already made history several times over. The year before she graduated, she became the first trans woman to intern at the White House. In 2016, she was the first trans person to speak at the Democratic National Convention.

Some of McBride’s most intense political feats, however, have happened out of the national spotlight. Lisa Goodman, attorney and president of lobbying arm Equality Delaware, remembers watching McBride take the floor of the Delaware Senate in 2013 as a fresh college graduate.

“She testified and took hostile questions on behalf of the trans nondiscrimination and hate crimes bill and handled it like someone who’d been doing it for 20 years,” Goodman said. This bill was the hardest that Goodman had ever worked on, she said — it passed with no votes to spare in the Delaware Senate, which more conservative at the time than it is now.

That moment in the Senate is Goodman’s top memory of her time working with McBride, whom she’s known for decades. She knew that McBride was lending humanity to a heated political debate with her very presence, while fielding hostile questions and baseless accusations that transgender women are men and would harm children in women’s bathrooms.

Debate on the Gender Identity Nondiscrimination Act marked the first time that a bill explicitly about transgender people had been brought before Delaware’s legislature.

“It’s one thing for me as a lesbian to stand up and talk about our brothers and our sisters. It’s another thing for people to be hostile to a trans person in-person,” Goodman said. “And that was a rough day and a rough crowd. And she just handled it with such grace and intelligence and integrity for such a young person. It’s something I’ll never forget.”

McBride’s experience in that chamber that she would one day be elected to — and then working to pass the Gender Identity Nondiscrimination Act in the Delaware House, where she would face even more anti-trans vitriol — marked a foundational change in her approach to combining the personal with the political. They were the same thing, she realized.

When first reaching out to legislators to back the bill, she had felt lost. She wanted to gain support through facts and statistics, not by talking about herself. But without doing that, she wasn’t actually using her voice. She needed to make a compelling case, and that meant letting in the emotion that she had been ignoring.

“For all of us, the political is personal. And the truth is this: Sometimes vulnerability is the best, or only path to justice,” she writes in her memoir. “Those with power or privilege won’t extend equality easily. Logic isn’t enough. The legislators had to see that transgender people are people. They had to understand our fears. Our hopes.”

McBride believes that Delaware is ready to be represented in Congress by a transgender woman who has spent her life in politics. That confidence is backed by more than just fundraising — her key endorsements indicate support from the political establishment, said Kelly Dittmar, associate professor of political science at Rutgers University and director of research at the Center for American Women and Politics. McBride has endorsements from Democratic state leaders and major PACs like Emily’s List, which holds particular sway with many women voters.

McBride’s Democratic opponents — state Treasurer Colleen Davis and Eugene Young, director of the Delaware State Housing Authority — have not received the same level of national or local endorsements as McBride, and are trailing her in fundraising, per their last quarterly reports via OpenSecrets.

McBride also believes that the campaign needs to be prepared to face anti-trans attacks — especially if, or when, Republicans realize what her win would mean.

In 2022 midterm races, Republicans embraced more anti-trans rhetoric than in any year that LGBTQ+ experts could remember. That rhetoric didn’t do them any favors in their campaigns, but the messaging from many candidates was brutal.

In this campaign, McBride has not yet been targeted by explicit anti-trans attacks — although she has experienced those in the past, she said. In 2020, recycled anti-trans tropes were used against her candidacy for the state Senate. Those same attacks may come again.

“We have to recognize that Republicans are going to realize there is a chance, a good chance, that we will shatter this national lavender glass ceiling in Delaware,” McBride said. “They understand that a critical piece of the puzzle that is missing from our ability as Democrats to push back on hateful and cruel anti-LGBTQ+ policies, is finally having an effective out transgender person in Congress working on all of the issues that matter, because we know that helps to diversify the narrative of who we are as a community.”