This column first appeared in The Amendment, a new biweekly newsletter by Errin Haines, The 19th’s editor-at-large. Subscribe today to get early access to future analysis.

‘Tis the season! Every four years as we head into a presidential election cycle, it’s the gift that keeps on giving: the political narrative that always asks, “What are Black voters going to do? Will they show up for Democrats?”

Headed into 2024, the narrative is no different. While Black voters — and particularly Black women — are still likely to be the Democratic Party’s most loyal and consistent base in November, there are signs that President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris are facing headwinds on the path to reelection. Among the challenges the campaign faces is not just whether Black voters will turn out for them, but whether some of them will turn out at all.

And it’s not just Black voters; Democrats are generally worried about voter enthusiasm and apathy, and polling suggests some of the hand-wringing may be warranted. The stakes could not be higher, with the future of democracy hanging in the balance as former President Donald Trump — who said earlier this month that he would be a “dictator on Day One” if reelected — remains the front-runner for the GOP nomination next year.

The Biden-Harris administration has had mixed results on key priorities for Black voters, coming up short on passing federal legislation on voting rights, gun reform and criminal justice, but securing record funding for historically Black colleges, record low unemployment and the first Black woman to serve on the Supreme Court. In the years since he has been out of office, Trump has continued to claim the 2020 election was stolen, largely by voters of color in battleground states. He also faces criminal charges for his alleged role in the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, a move to attempt to overturn the election results to preserve Trump’s presidency.

The former president has already signaled his plans to subvert how government and our democracy works if reelected, making the 2024 contest feel existential.

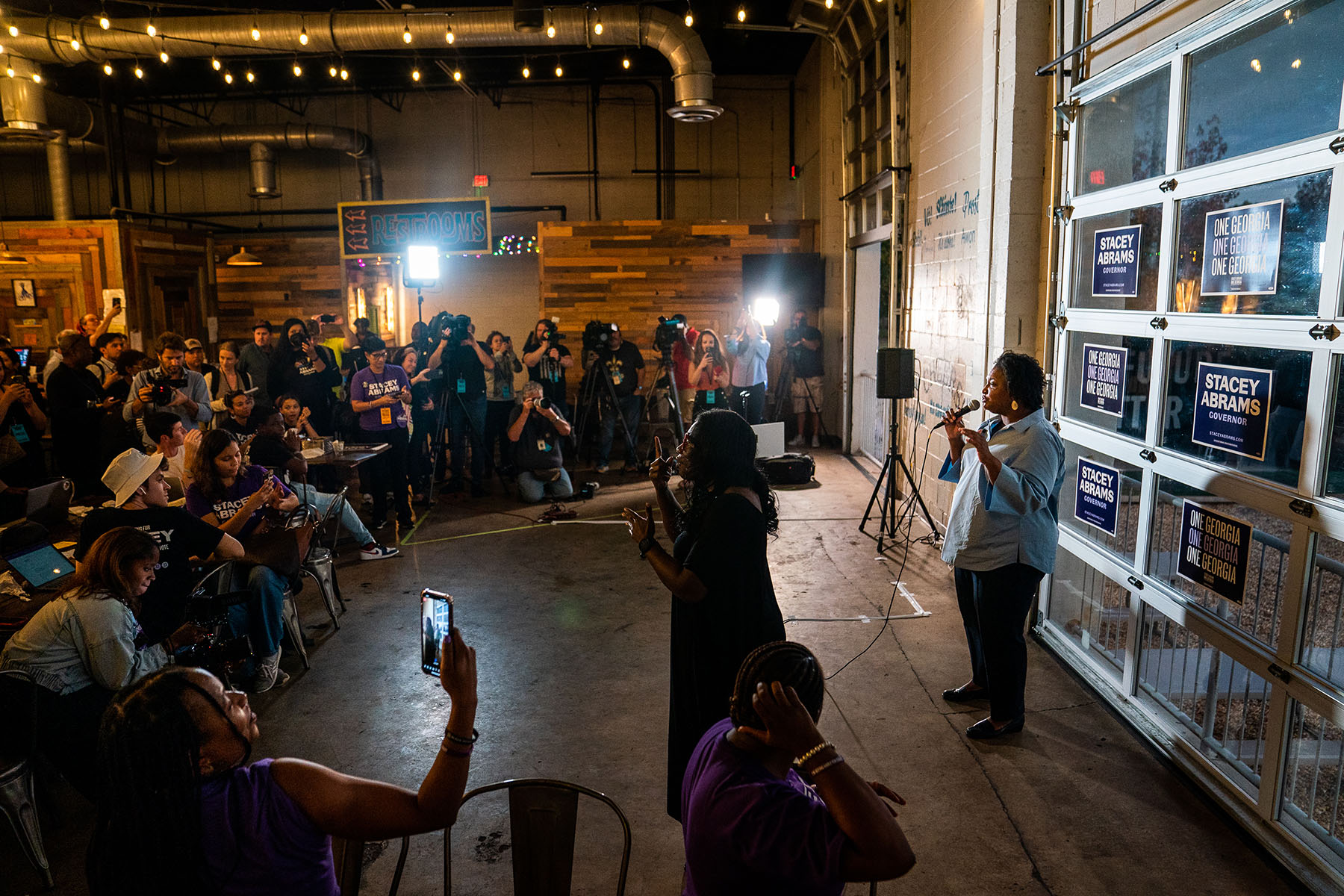

To win, Democrats will need to reach voters early, including the Black voters who often complain candidates show up too late, focused on their output and not their input. Presidential and other campaigns have to do this work, but it’s an organizing model that is getting a new member. The new Renegade Collective is focused on the South — where most Black Americans live and vote — both for 2024 and for the longer term. It’s made up of a group of political strategists who helped Stacey Abrams build the winning coalition that flipped Georgia from red to blue in 2020 and 2022 — and brought Abrams within striking distance of becoming the first Black woman to be elected governor in 2018 and 2022.

Now, they’re betting they can replicate that success outside of Georgia.

“There was a feeling after the election that there’s still work to be done, that our democracy is still under attack and we had put together a formula that helped increase voter participation in a way that hadn’t been seen … in terms of really thinking about folks who don’t typically engage in the process and really finding ways of making them feel like they were a part of the conversation, that they were relevant and they mattered,” said Lauren Groh-Wargo, Abrams’ former campaign manager and member of the new Renegade Collective.

Organizers with the Abrams team were among those who bucked the traditional turnout-focused campaign strategy of chasing more reliable voters who could be counted on to show up on Election Day. Instead, they looked to expand the electorate by focusing on “low-propensity” voters, people who didn’t participate regularly in the electoral process and who were mostly seen by campaigns as not worth the effort or outreach.

This included Black voters who were previously unregistered or otherwise less engaged, but it was also about putting together a coalition that was multiracial, intergenerational, both rural and urban, and largely disaffected. An approach that centered their priorities — and not the candidates — was the persuasion argument that helped deliver seismic political victories for Democrats in Georgia in 2020 and 2022. The coalition was the culmination of a decade of work that helped turn Georgia blue for the first time in a generation, electing Biden and Harris, and two history-making Democratic U.S. senators.

Several of the organizers who are now part of the Renegade Collective said they’ll have a continued approach of meeting voters where they are — and then listening to them.

“Every event that we did was a focus group,” said Justin Kirnon, Abrams’ statewide political director in 2022 and a veteran of Georgia politics and policy work in areas including public safety, transportation and local government. “A lot of the places where we would go, people would say, ‘Politicians don’t come here.’”

Cigar and hookah bars. Motorcycle meetups. Music festivals. High school and professional football tailgates. Family reunions. “Where there were people we needed to vote, we would go, and it wasn’t just during the campaign,” Kirnon said.

To be successful, The Renegade Collective, along with other groups and political campaigns, will also have to engage and educate voters early, particularly young voters concerned about what’s happening to their rights, gun violence, the threat of white supremacy and the lack of justice. When it comes to the voter mobilization ecosystem, the more, the merrier, said Melanie Campbell, president and CEO of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation, a nonpartisan group focused on Black women.

“There’s not enough of us, and we all need to do all we can to work together to be that much more powerful,” said Campbell. “There’s a lot of work out here to be done. I can’t say one organization is going to do it all. I’m a daughter of the South and I’m a firm believer that if things can go well in the South, so goes the nation. And because most Black people live in the South, if we’re worried about Black America, we have to be worried about making sure our rights and freedoms are protected.”

In the span of a few election cycles, Moncello Stewart, part of the Renegade Collective, went from being a low-propensity voter to a super voter and organizer. Based in Savannah, Georgia, he said organizers will have to do a better job of informing people whose mindset is like his used to be.

“The problem is, right now, people are so upset with the national (Democratic) party, they don’t know where the wins are,” Stewart said, especially Black men. “I was never like, I really want to get into this, until I started getting people to talk to me on my level.”

That changed in 2018 with Abrams’ first gubernatorial campaign.

“Somebody spoke to me, they didn’t make me feel disenfranchised because I had locs or wore a gold grill sometimes on the weekends, or because I like to wear Jordans,” Stewart said. “Those things really matter.”

“A lot of states in the Deep South are particularly ripe for this type of intervention,” said Renegade Collective member Jack DeLapp, citing South Carolina and Mississippi as examples of states with significant Black populations and adding that there are also more conservative White voters in those states than in Georgia so the strategy can’t be exactly the same.

Black voters joined progressive Whites to make gains in states including Mississippi and North Carolina in recent cycles, but still fell short in some key statewide races. The South remains challenging in many ways for Democrats, and the organizing that happened in Georgia over the course of years isn’t easily replicable.

“I’m of two minds: On the one hand, the Abrams coalition did put together, twice, something that was really remarkable in terms of registration, grassroots organizing and education,” said Fordham University political scientist Christina Greer. “They also had a candidate that was once-in-a-generation, in a state that already had a lot of organizing infrastructure, a number of HBCUs, a civil rights legacy and demographic shifts in a state that helped Democrats.”

As we look to 2024, beleaguered Black voters are saying they’re open to someone else, or to staying home. But it’s not just on Black voters to join the big tent Democrats will need to win; victory takes a coalition. How will Asian and Latino voters — neither of whom are monolithic, either, by the way — factor into this cycle? And while demographics aren’t destiny, they do present an opportunity. Regardless of the results for Democrats in 2024, Black voters shouldn’t be solely blamed for a loss, but they can be credited for helping with the wins.

What Southern White voters will do — and the group’s ability to appeal to them to join in coalition — will also be part of the equation, Greer said.

“In statewide elections, it’s not just up to Black voters to do the heavy lifting,” she said. “It’s White voters who are the changemakers.”

The people behind the Renegade Collective in Georgia were able to prove that many White voters, particularly in the South, also can’t be taken for granted. For them, showing up counts too — and can lead to surprising results in a region of the country some assume is a political lost cause for Democrats.

Observers and organizers both inside and outside of the party agree that, for Biden and Harris and the Democrats to win, the time to make the case is now, and it’s a pitch that requires voters to recognize their power, as much as any politician’s, to make change. In this election, I’ll be watching how campaigns and organizers appeal to voters, for what we can learn about the electorate now and for the future of our democracy.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled the names of Moncello Stewart and Jack DeLapp.