Every morning as soon as Amy Broadnax wakes up, she opens the weather app on her phone to check the temperature in Marlin, Texas.

“If it’s over 80 degrees, I know my daughter’s going to have a hard day. She might die,” Broadnax told The 19th.

Broadnax’s 27-year-old daughter is incarcerated in the William P. Hobby Unit, a women’s prison about 100 miles northeast of where Broadnax lives in Austin. This past summer was the second hottest on record in Texas, with an average temperature of 85.3 in June, July and August. Even after summer officially ended, temperatures above 80 degrees have persisted into early October.

As the weather begins to cool, Broadnax said her worries are not over. She thinks back to the past two winters, when Texas was hit with freezing cold, icy conditions or snow storms that overburdened the state’s resources. Broadnax recalls hearing from her daughter that women inside the prison would try to huddle together for warmth but would be scolded by the guards.

In recent years, Texas has emerged as a focal point in a nationwide conversation about temperature control inside prisons and jails and the dangers that both severe heat and cold pose to incarcerated people. In both extremes, incarcerated women are among the most vulnerable. Many of them enter prison with preexisting physical or mental conditions that can worsen with harsh temperatures.

Only a quarter of Texas’s 107 prisons have air-conditioning throughout the facility. The majority of the 12 women’s prisons in the state have partial air-conditioning, which could mean specific rooms in the building or some sleeping areas having access to cool air.

In letters provided to The 19th by the nonprofit Lioness Justice Impacted Women’s Alliance, one incarcerated woman describes being in a prison unit with air-conditioning that officials would turn on only at night, rather than during peak heat hours in the day. Another letter said women in the Hobby unit were receiving cold water to drink only every 4 to 5 hours.

These realities highlight a larger national trend, even in the country’s hottest states. A 2019 report from the research nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative found that 13 states in the hottest regions of the country lack universal air-conditioning in their prisons. This year, the extreme heat wreaked havoc on prisons around the country, and coincided with an increase in illnesses and deaths in the facilities.

Without accounting for prison temperatures, women in prison are most likely to die from cancer, heart disease and “other illnesses,” BJS said in a 2021 report. Suicide was the fourth most prevalent manner of death for women in prison.

About two-thirds of incarcerated women enter prison or jail with a chronic physical condition. Women are also more likely than men to experience “serious psychological distress,” according to the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Additionally, U.S. prisons and jails see about 58,000 admissions of pregnant women each year.

Severe conditions both hot and cold create additional health challenges for a population that already experiences disproportionate medical issues.

“What happens depends on our own individual physiology, but in general, our organs, our heart, or kidneys, or lungs, are not designed to function in hotter temperatures than what’s in our core. That’s why we see a range of consequences. For example, we know after a heat wave that about half of all the excess deaths are from cardiovascular causes,” said Kristie L. Ebi, a professor in the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the University of Washington.

If the body organs and defense systems are already working harder in response other health issues, this can accelerate the harmful effects of acute temperatures.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice has not classified a prison death as heat-related since 2012, but Brown University researcher Julie Skarha identified nearly 300 deaths in Texas between 2001 and 2019 that can be attributed to extreme heat exposure. “In Texas prisons, we’re seeing a 30-fold increase in heat-related mortality compared to the U.S. general population,” she said.

Prison Policy Initiative research indicates that incarcerated people in Texas who were most vulnerable to high temperatures include those with asthma or those taking medicine for high blood pressure or psychiatric issues.

In June, 37-year-old Elizabeth Hagerty, a woman who had high blood pressure, diabetes and asthma, died in her Texas prison cell that lacked air-conditioning in 100-degree weather. In one letter written to Lioness, two incarcerated women said that Hagerty had a sign in her cell window that read, “please give me water,” but she was ignored.

Now, with fall and winter, advocates said they fear the subject of temperature control in prisons could see a decline in public interest.

“What I worry could happen is that the issue will become an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ kind of thing,” said Marci Marie Simmons, the community outreach coordinator for Lioness Justice Impacted Women’s Alliance. “We have a pretty good momentum going currently with spreading awareness on this issue. At Lioness we’re trying to think of how we can keep things moving forward.”

But while many people associate Texas with mild winters, low temperatures pose another set of challenges. People in the South can actually be more susceptible to harmful effects during cold waves because their bodies are not adapted to that climate and the surrounding infrastructure is not built to handle colder conditions, Skarha said.

This is especially problematic for people in prisons who have little ability to grab a blanket or warmer clothing when needed.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice told The 19th that all of its prisons have adequate heating. But in 2018, the Texas Inmate Families Association reported that about 30 prisons had malfunctioning or insufficient heaters during a cold wave in the state. During the historic 2021 Texas ice storm, the state’s electrical grid failed, leaving 33 prisons without power and about two dozen with water shortages in below freezing temperatures.

“The Texas Department of Criminal Justice was clearly not equipped to handle an extreme winter,” said Amite Dominick, president and founder of Texas Prisons Community Advocates, which works with people who have been affected by the state’s prison system. “The generators failed, the pipes clogged up, we had testimony that people had frostbite. If we see an extreme winter again, we’re going to have problems.”

Beyond the immediate physical and mental threats, extreme temperatures can also increase irritability and instances of violence in prisons, said Michele Deitch, director of the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin. She pointed to a statewide lockdown in September following a rise in violence and illegal contraband.

Though the state did not tie these incidents to the summer heat wave, the resulting lockdown restricted most inmates to their cells for 24 hours for more than a week as the heat continued to surge.

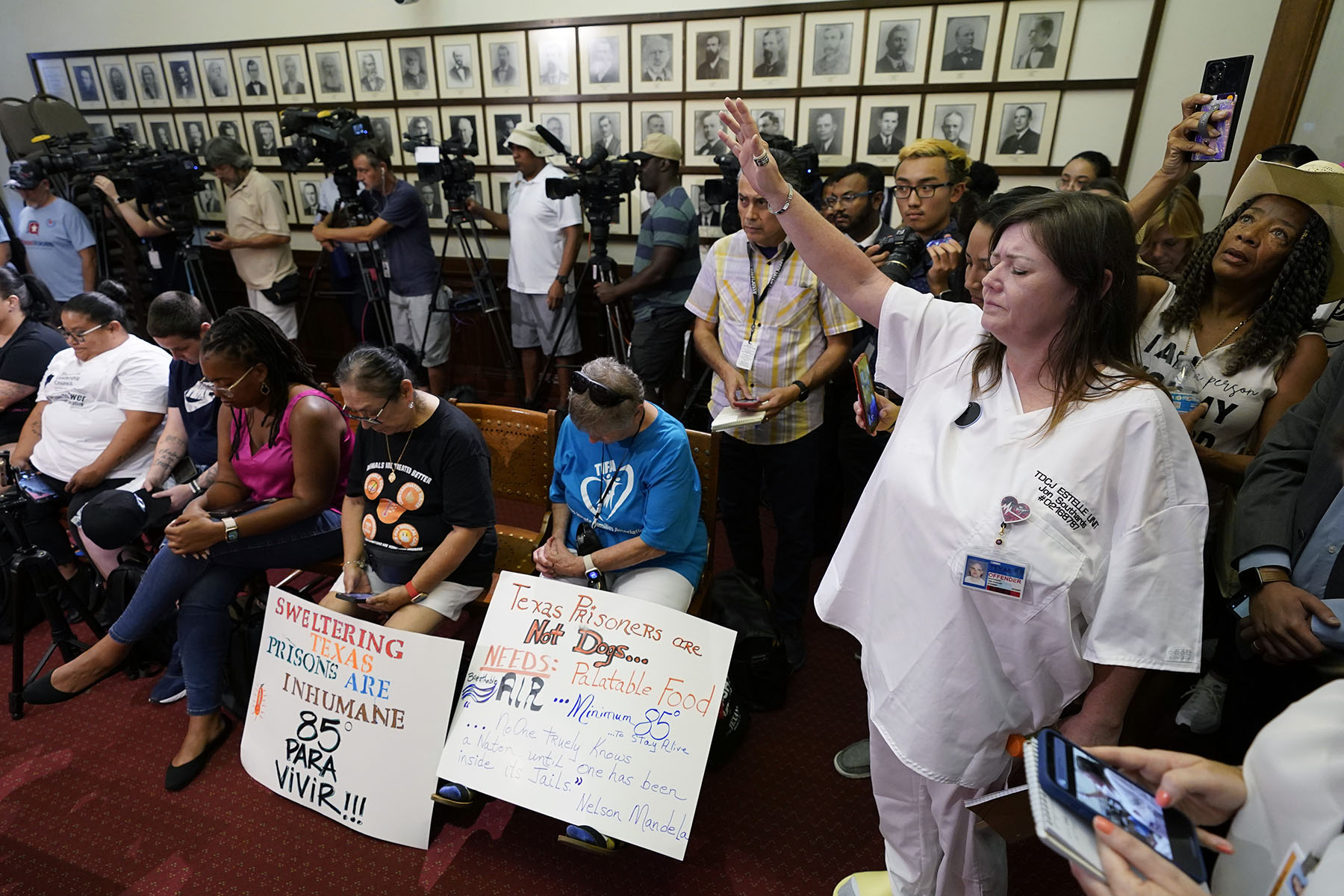

Organizations like Lioness Justice Impacted Women’s Alliance and Texas Prisons Community Advocates have been calling for the state to mandate temperature control between 65 and 85 degrees. That requirement already exists for Texas jails, but state prisons are a different jurisdiction.

Advocacy groups have demanded state action for several years but the legislative proposals have stalled in the Texas senate.

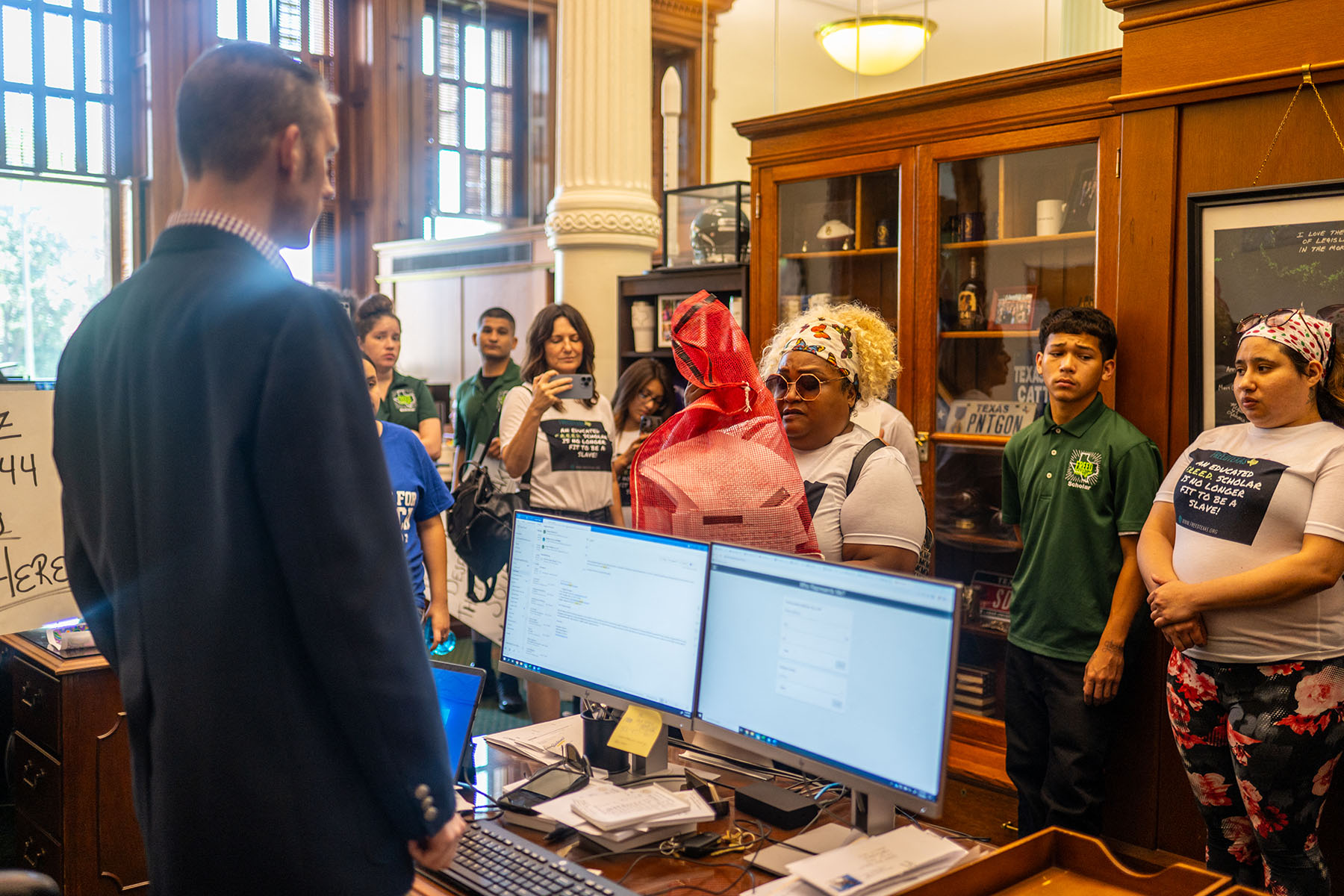

Dominick of Texas Prisons Community Advocates said she understands public interest in these issues ebbs and flows, but she believes there’s an opportunity to continue to bring awareness on a national level.

“I think now can be a time for more pinpointed efforts towards developing and cultivating the conversations that began during the heat,” she said. “So you don’t stop the conversation. You just dig a bit deeper into the conversation.”