Your trusted source for contextualizing education news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

“How can young women really see their value if they don’t see their place in history?”

That’s the question Kristen Kelly, a teacher at Sacred Heart Preparatory in Atherton, California, asked herself a decade ago after struggling to find a high school textbook that meaningfully engaged women’s contributions to history.

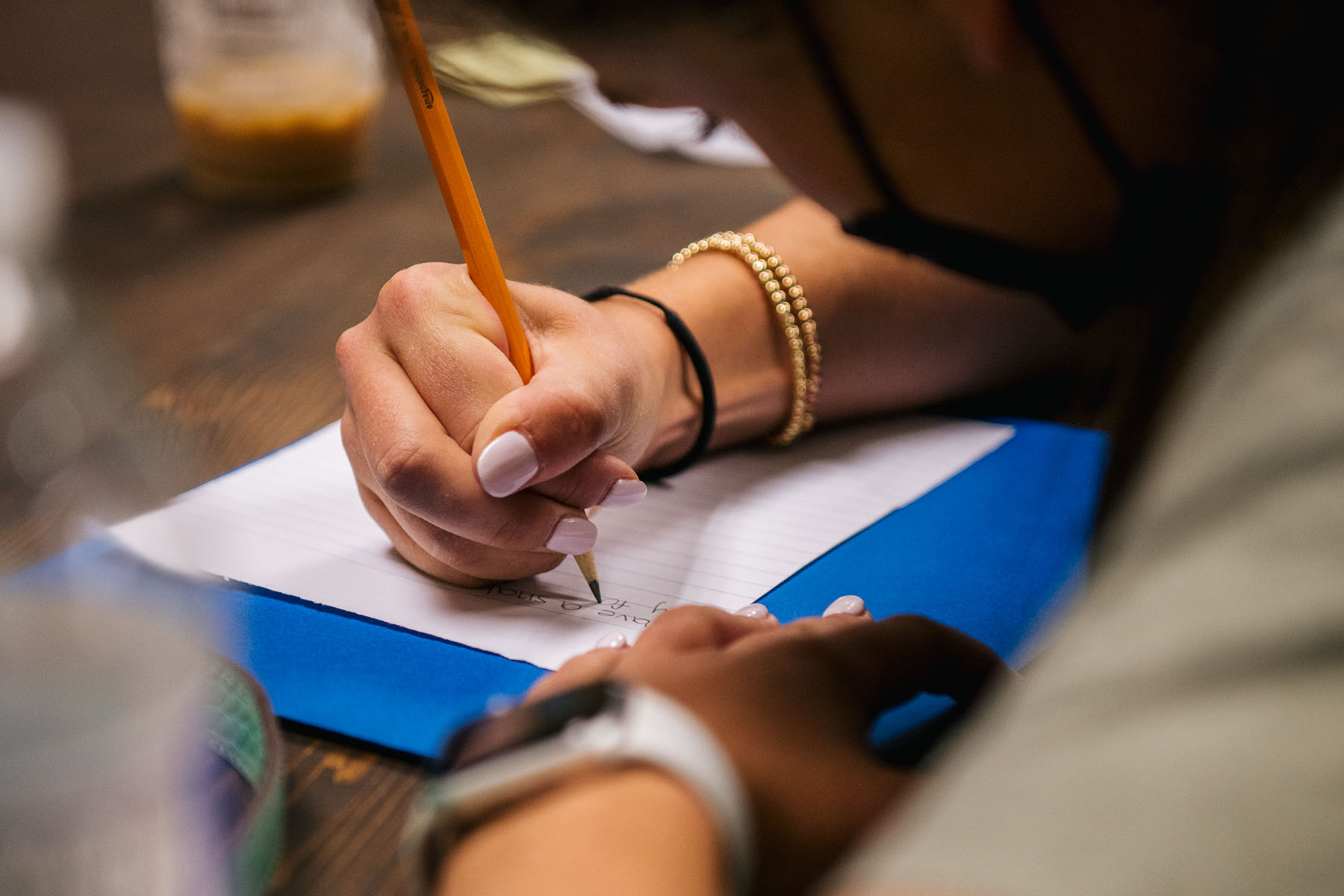

At the time, Kelly taught religious studies, and when she expressed her frustrations to Sacred Heart history teacher Serene Williams, she learned that they both shared the same concern. So, the two teamed up on an interdisciplinary women’s history class, creating a reader to accompany the coursework.

Now the women are on a mission to center women in high school history courses across the country. They are petitioning the College Board — the not-for-profit organization that administers Advanced Placement courses — to offer an AP U.S. Women’s History course. So far, they have collected nearly 2,000 signatures to that end.

The dearth of women’s political history in AP U.S. Government and Politics, which Williams has years of experience teaching, is a major reason the educator believes in the necessity of an AP course devoted solely to women’s contributions in the United States. That none of the foundational documents included in AP U.S. Government are written by women and few questions on the exam for the course are about women disturb both Williams and Kelly, who contend that the class should be more intersectional.

“I feel like it messages that women are not foundational to our political system,” Williams said.

Although Williams and Kelly’s concerns about women’s exclusion from high school history curricula go back over a decade, they did not set out to propose a standalone course on women’s history. After winning a 2022-23 Schlesinger Library Teaching Grant from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University, the duo intended to conduct research at the Schlesinger Library that would support making AP U.S. Government more inclusive of women.

But when the College Board began to pilot new courses, particularly AP African American Studies — which rolled out this year despite objections from lawmakers in states such as Florida and Arkansas — the educators decided to campaign for AP U.S. Women’s History. They’ve been petitioning the College Board, making presentations with students about the proposed course and attending conferences to pitch the class, with plans to go to the College Board’s Advanced Placement Annual Conference next year.

The Women’s History in High School website created by Kelly and Williams outlines the subject matter their proposed course would include, and it’s far-ranging. It would begin by covering women’s roles in Indigenous societies before the Americas were colonized and would go on to cover the American Revolution, Seneca Falls, Manifest Destiny, the Civil War and the Gilded Age — all with women’s issues at the forefront. From there, the course enters the 20th century, examining both world wars, second- and third-wave feminism and the conservative backlash to feminism, before ending in the present day with a focus on contemporary women’s issues and trailblazers.

“The first wave of feminism is typically taught in high school from 1848, Seneca Falls, to 1920,” Williams said. “And if students learn anything about women’s political history, they typically learn it that way. So our course spends a lot of time talking about pre-1848, what women’s political authority in this land looked like. We talk a lot in this course about common law and how women actually lost political authority when the Constitution went into effect. We talk a lot about the impact of chattel slavery on women’s political bodies and regulation by the state.”

The course includes women from multiple ethnic, religious and political backgrounds as well as women who belong to the LGBTQ+ and disability communities. The sheer diversity of women named Phyllis (or a variation) in history is a case in point. There’s Phillis Wheatley, the enslaved poet who as a teen in 1767 became the first Black American to have her work published; Phyllis Schlafly, the White conservative who led a movement to block the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s; and Phyllis Lyon, the lesbian and marriage equality activist who died just three years ago.

“The centering line around this has always been intersectionality, and really, really trying to make sure every voice in the gender experience is expressed and heard,” Kelly said. “To be honest, our curriculum is crowdsourced. Our students teach us new things every day, and we really try to access their personal experiences. So it’s a beautiful kind of personalized, intersectional experience.”

The College Board did not make any officials available for an interview about whether the organization would consider offering an AP U.S. Women’s History course, but a spokesperson did provide The 19th with the criteria it uses to assess potential courses.

“Key to that process is colleges and universities’ willingness to award college credit and placement to students who achieve qualifying AP exam scores,” the spokesperson told The 19th. “Additionally, we evaluate new courses to determine if there is significant demand for the course in high schools. Finally, the launch of the course must also serve the Advanced Placement program’s mission to expand access to a broader student population.”

The College Board considers the diversity of the student population who might take the course and exam and if at least 500 high schools indicate intent to offer the course when it launches. It also considers whether a minimum of 200 colleges and universities will award credit for a qualifying exam score on the course and how consistent college syllabi are on the proposed course, the spokesperson said. In other words, do colleges approach the topic relatively similarly?

-

More from The 19th

- Changes to AP African American Studies course set a ‘scary precedent,’ advocates say

- States are banning LGBTQ+ subjects in schools. Most students say they were never taught about them anyway.

- Mainstream education often neglects Black history. TikTok, Freedom Schools and other resources are bridging the gap.

Lauren Cheng, a high school senior in California’s San Francisco Bay Area, said that she would appreciate an Advanced Placement course on women’s history. She’s taken seven AP classes, including AP U.S. History and AP U.S. Government and Politics, but none have substantially highlighted women’s contributions to society, she said. The same goes for the other courses she’s taken throughout her K-12 career.

“Throughout my education in history, the dominant narrative was always male,” Cheng said. “I would say a lot of history — world history and U.S. history — is all from the male perspective, or specifically the White male perspective.”

In her AP U.S. History class, she did learn about the Grimké sisters, who were abolitionists and women’s suffragists. She especially enjoyed learning about Hazel Ying Lee, the first Chinese-American woman to fly for the Women Airforce Service Pilots during World War II, because she felt that someone who shares her gender and ethnic background was finally being highlighted. But Cheng added that her teacher made a point to tell the class about Lee, who was not centered in the AP curriculum.

Cheng, a classmate of Williams’ niece, said that she’s looked at the proposed AP U.S. Women’s History course and is saddened that she’s never encountered most of the women’s names included.

“There’s a lot of names that I don’t recognize,” she said. “And I think it’s really important that everyone can have the opportunity to learn about women’s impact throughout history. I think it could create a more equitable society in general if that perspective is taught, especially at a young age.”

Williams said that the addition of the proposed course could make AP courses more relevant and appealing to students, especially as the College Board faces pushback from conservative lawmakers who have suggested dropping AP courses altogether.

“Everybody should be able to access education,” she said. “We feel like women and, particularly, young girls, should be able to access their narrative. Women were always there. Regardless of where they go, the boardroom, the operating room, wherever they work, they should always know they were always part of the story. You can’t embrace the historical narrative unless you see yourself in the story.”