When Texas A&M University announced last month that it had hired a director to revive its journalism school, it included the kind of fanfare usually reserved for college coaches and athletes.

The university set up maroon, silver and white balloons around a table outside its Academic Building for an official signing ceremony. It was there that Kathleen O. McElroy, a respected journalist with a long career, officially accepted the position to run the new program and teach as a tenured professor, pending approval from the Texas A&M University System Board of Regents.

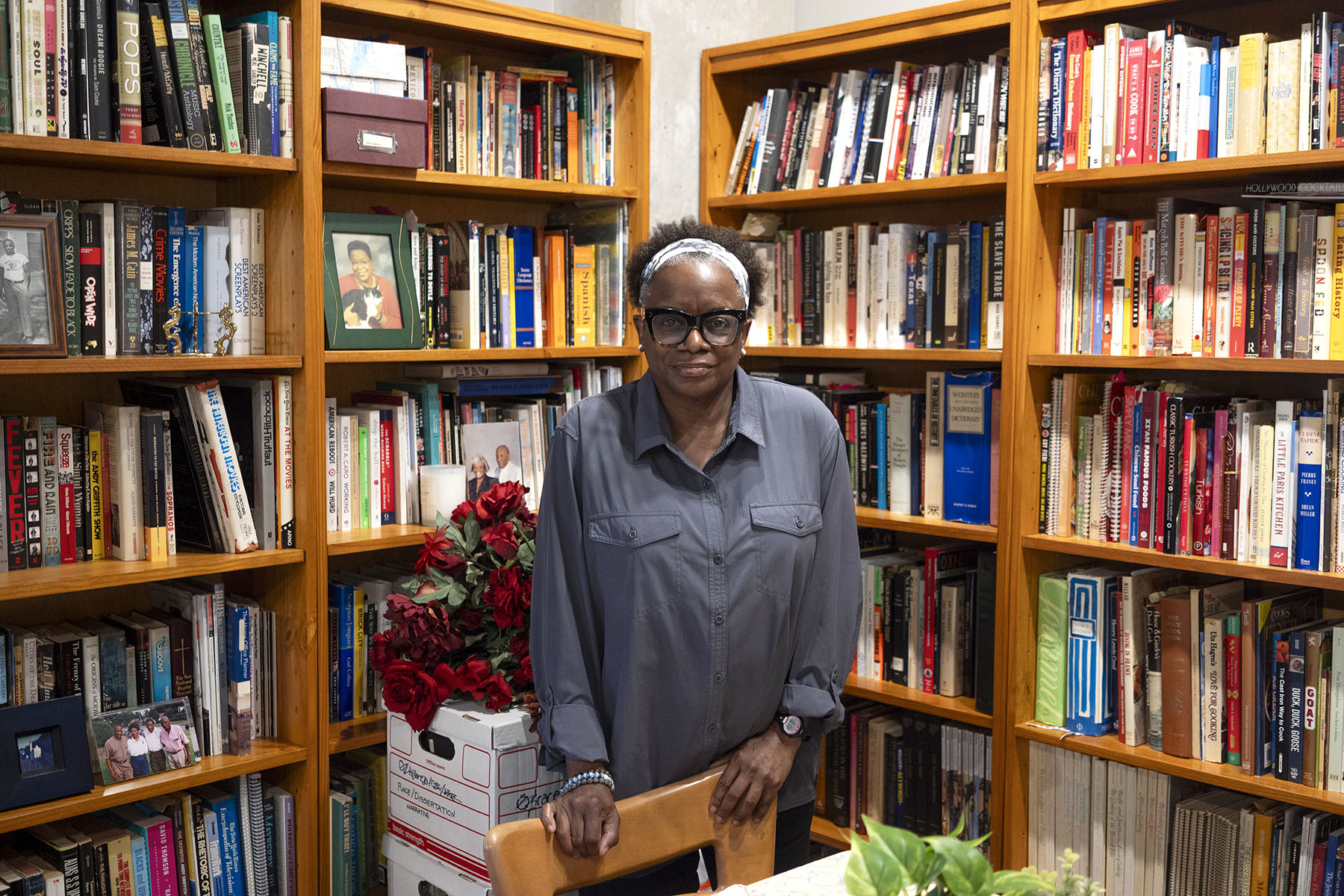

McElroy, a 1981 Texas A&M graduate, was the director of the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Journalism between 2016 and 2022, where she is a tenured professor. Before that, she spent 20 years in various editing roles at The New York Times until heading to UT-Austin to pursue her doctorate.

She has studied news media and race, with a focus on how to improve diversity and inclusion within newsrooms, and spent her career covering other areas like sports and obituaries. Her master’s thesis focused on the obituaries of civil rights leaders. Now, she was excited to head back to her alma mater to build a brand new program there.

But in the last several weeks, McElroy told The Texas Tribune, the deal with Texas A&M fell apart.

In the days after the signing ceremony, she said, A&M employees told her an increasingly vocal network of constituents within the system were expressing issues with her experience at the Times and with her work on race and diversity in newsrooms, McElroy said.

Behind the scenes, A&M spent weeks altering the terms of her job. After hearing about the concerns, McElroy agreed to a five-year contract position without tenure, which would have avoided a review by regents. On Sunday, she received a third offer, this time with a one-year contract and emphasizing that the appointment was at will and that she could be terminated at any time. She has rejected the offer and shared all of the offer letters with the Tribune.

The situation comes at a fraught time at Texas public universities. Schools are preparing for a new state law to go into effect in January that bans offices, programs and training that promote diversity, equity and inclusion. Recently, the Texas A&M System started a systemwide audit of all DEI offices in response to the new law.

Conservative Texans — from locally elected public school trustees to top state officials — have labeled several books and schools of thought that center the perspectives of people of color as “woke” ideologies that make white children feel guilty for the country’s history of racism. Last month, the U.S. Supreme Court banned the consideration of race in college admissions, effectively ending affirmative action in American higher education.

McElroy said she was told that her appointment was caught up in “DEI hysteria” as Texas university leaders try to figure out what type of work involving race is allowed.

-

More higher education coverage

- The Supreme Court ends affirmative action in college admissions

- What will happen without affirmative action in colleges? University leaders fear a lapse in diversity efforts.

- The Supreme Court blocked Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan. Repayments will resume this fall.

“I feel damaged by this entire process,” said McElroy, who is a Black woman and a native of Houston’s Third Ward, and whose father, George A. McElroy, was a pioneering Black journalist. “I’m being judged by race, maybe gender. And I don’t think other folks would face the same bars or challenges. And it seems that my being an Aggie, wanting to lead an Aggie program to what I thought would be prosperity, wasn’t enough.”

A Texas A&M University spokesperson did not immediately respond to a list of emailed questions about the issue.

On Friday, McElroy said, she got a call from A&M’s interim dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, José Luis Bermúdez, warning her that there were people who could force leadership to fire her and he could not protect her.

The call came one day after the Texas A&M University System Board of Regents met and discussed personnel matters in executive session, according to a posted agenda. The board discussed McElroy’s hiring with Texas A&M President M. Katherine Banks, according to a person familiar with the situation.

According to McElroy, Bermúdez told her that her hiring had “stirred up a hornet’s nest,” that there were people against her and that, “even if he hired me, these people could make him fire me … that the president and the chancellor, no one can stop that from happening,” she said.

Ultimately, he advised her to stay in her tenured role at UT-Austin.

On Sunday, she received the latest iteration of an offer letter, which was different from the one she publicly signed on campus. Texas A&M was now offering her a one-year contract as a professor without tenure, and a three-year appointment as the director of the journalism program, though it noted that she could be fired at any time, she said.

“This offer letter on Sunday really makes it clear that they don’t want me there,” she said. “But in no shape, form or fashion would I give up a tenured position at UT for a one-year contract that emphasizes that you can be let go at any point.”

Weeks after the public celebration about the new A&M position, she has rescinded her resignation at UT and will stay in Austin, according to an email sent to that school’s journalism department Tuesday morning and obtained by the Tribune.

In a statement, Bermúdez said Texas A&M policy does not allow him to comment on personnel deliberations.

“However, we can confirm that Dr. McElroy has an offer in hand and that we have not been notified her plans have changed — we hope that’s not the case. We certainly regret any misunderstanding that may have taken place,” he said in a statement.

Reviving a defunct program

When Banks announced that the university would bring back its journalism program in 2021, it was an exciting moment for many students, faculty and alumni.

Texas A&M had dropped its journalism program in 2004 after 55 years, though it continued to offer it as a minor and then as a liberal arts degree.

The Texas A&M University System Board of Regents, which oversees the university, approved the new major in February. It is still waiting for final approval from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

McElroy said the university started to woo her last summer, at first as a consultant as it relaunched the program and then to possibly run it.

According to the original offer letter that she signed during the June 13 ceremony, McElroy was hired as a tenured professor in the Department of Communication and Journalism and as the journalism program’s director, without an end date to her appointment. Still, the Texas A&M University System Board of Regents, whose members are appointed by the governor, would have to approve her tenure position.

McElroy’s responsibilities had little to do specifically with diversity or equity, she said. She was hired to help build a curriculum that specifically addresses delivering news to underserved audiences across the state, as well as growing the program, hiring faculty and helping expand its internship program for future student journalists.

That’s the kind of work that McElroy is known for, journalism experts said.

“She’s always constantly trying to improve opportunities for journalism students so they can enter the career and continue building out great storytelling,” said Judy Oskam, director of the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Texas State University. “That’s what I always think of when I think of Kathleen.”

When A&M suggested that it announce McElroy’s hiring with a signing day, McElroy said she didn’t want the attention.

“But I was willing to go along with it because if A&M wanted to celebrate journalism, then I want to be a part of that,” she said.

Backlash

The signing ceremony got a huge positive response on social media, according to an email sent to McElroy by the university’s social media coordinator.

“This is one of the most positively received stories we have shared during my time at [marketing and communications],” wrote Jacob Alan Svetz, a social media coordinator at Texas A&M, in an email to McElroy. “Of the hundreds of posts congratulating Texas A&M, Arts and Sciences, and Kathleen, I saw two negative posts— pretty unheard-of levels of positIvity for today’s internet.”

But within days, the conservative website Texas Scorecard wrote a piece emphasizing McElroy’s work at UT-Austin and elsewhere regarding diversity, equity and inclusion and her research on race, labeling her a “DEI proponent.”

That website is the reporting arm of Empower Texans, a Tea Party-aligned group formed with millions in oil money that holds considerable influence over Texas officials. Empower Texans and its affiliated groups blur the lines between newsroom, lobbying firm and political action committee. It has aimed to upend Texas politics with pricey primary challenges to replace moderate Republicans with hard-line conservatives.

In a statement, Texas A&M defended McElroy to Texas Scorecard, calling her a “superb professor, veteran journalist and proven leader.”

“She has worked for newsrooms for 30 years, and has led journalism programs at two Tier 1 research institutions,” the university told Texas Scorecard. “Her track record of building a successful curriculum — coupled with her deep understanding of the media landscape — positions her uniquely to lead the new program.”

But McElroy said she had a conversation with Bermúdez, the interim arts and sciences dean, on June 19 that struck a different tone.

According to written notes McElroy took during the calls and provided to the Tribune, Bermúdez said he wanted her to “go into this with eyes open” and that Texas A&M is different from UT-Austin in terms of its politics and culture. McElroy said she was told that she had a big target on her back.

Bermúdez said there were concerns about McElroy going through the tenure process, which requires the approval of the board of regents.

McElroy said that Bermúdez told her that “it might be wise to consider all the ways the wheels might come off.” In that conversation, McElroy said they alluded to what happened to journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones when the University of North Carolina’s board of trustees denied her a tenured position a few years ago because of her Pulitzer Prize-winning work covering on race in America, despite a recommendation for tenure from the university’s journalism department. Texas lawmakers have banned Texas public schools from requiring students to read work spearheaded by Hannah-Jones.

Ultimately, McElroy said, Bermúdez convinced her not to go for tenure. Instead, she agreed to be a professor of practice with a five-year contract.

A few days later, they had another conversation in which Bermúdez suggested McElroy give a presentation to the board of regents at its August meeting about her vision for the program, she said.

McElroy was further told there was “noise in the [university] system” about her, though he did not give specifics and told her that in some conservative circles, The New York Times is akin to Pravda, the newspaper of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union in the early 1900s.

On June 26, McElroy met with Bermúdez and Susan Ballabina, chief external affairs officer and senior vice president for academic and strategic collaborations, to walk through the presentation to the board of regents in August. She was told to see the presentation as an opportunity to tell the regents who she is and how she fits within Aggie core values.

McElroy said she left that conversation feeling positive.

“I’m gonna wow them, I’m looking forward to this and I’m hoping I can even get money from these folks,” she remembered thinking.

But then she got a call from Bermúdez on Friday afternoon that quickly erased those good feelings when he told her people outside the university could force the school to find a new director and no one could stop it.

On Sunday, the new offer came in for a one-year contract to teach and a three-year appointment as director.

Ultimately, McElroy said she was surprised by the backlash. She said as reality set in during these talks, she remarked that she was so disappointed that not much had changed about the culture at Texas A&M since she was a student in the ’70s and ’80s. She said the university insisted it was different. It was better.

“Well, it doesn’t feel that way,” she said.

Disclosure: Texas A&M University, The New York Times, the Texas A&M University System and the University of Texas at Austin have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared here in The Texas Tribune.

The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.