The White woman at the center of the Emmett Till saga, Carolyn Bryant Donham, has died.

Megan LeBoeuf, chief investigator for the Calcasieu Parish coroner’s office, confirmed Donham’s death. The 88-year-old was suffering from cancer and was receiving end-of-life hospice care.

Devery Anderson, the author of “Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement,” said Donham’s death marks the end of a chapter.

Some people “have been clinging to hope that she could be prosecuted. She was the last remaining person who had any involvement,” he said. “Now that can’t happen.”

For many, “it’s going to be a wound, because justice was never done,” he said. “Some others were clinging to hope she might still talk or tell the truth. … Now it’s over.”

Till’s cousin, Wheeler Parker, said he and his family send their sympathies to the Donham family. “We don’t have any ill will or animosity toward her,” he said.

He said Till’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, forgave her son’s killers.

In a speech she made shortly before her 2003 death that God told her not to hate her son’s killers. “I am glad he took hatred out of my heart,” she said.

The killers thought they would be heroes, but became nobodies who lived miserable lives, she said. “There’s one sentence that you cannot escape, and that is when you go before the judgment seat of God. He will give the verdict.”

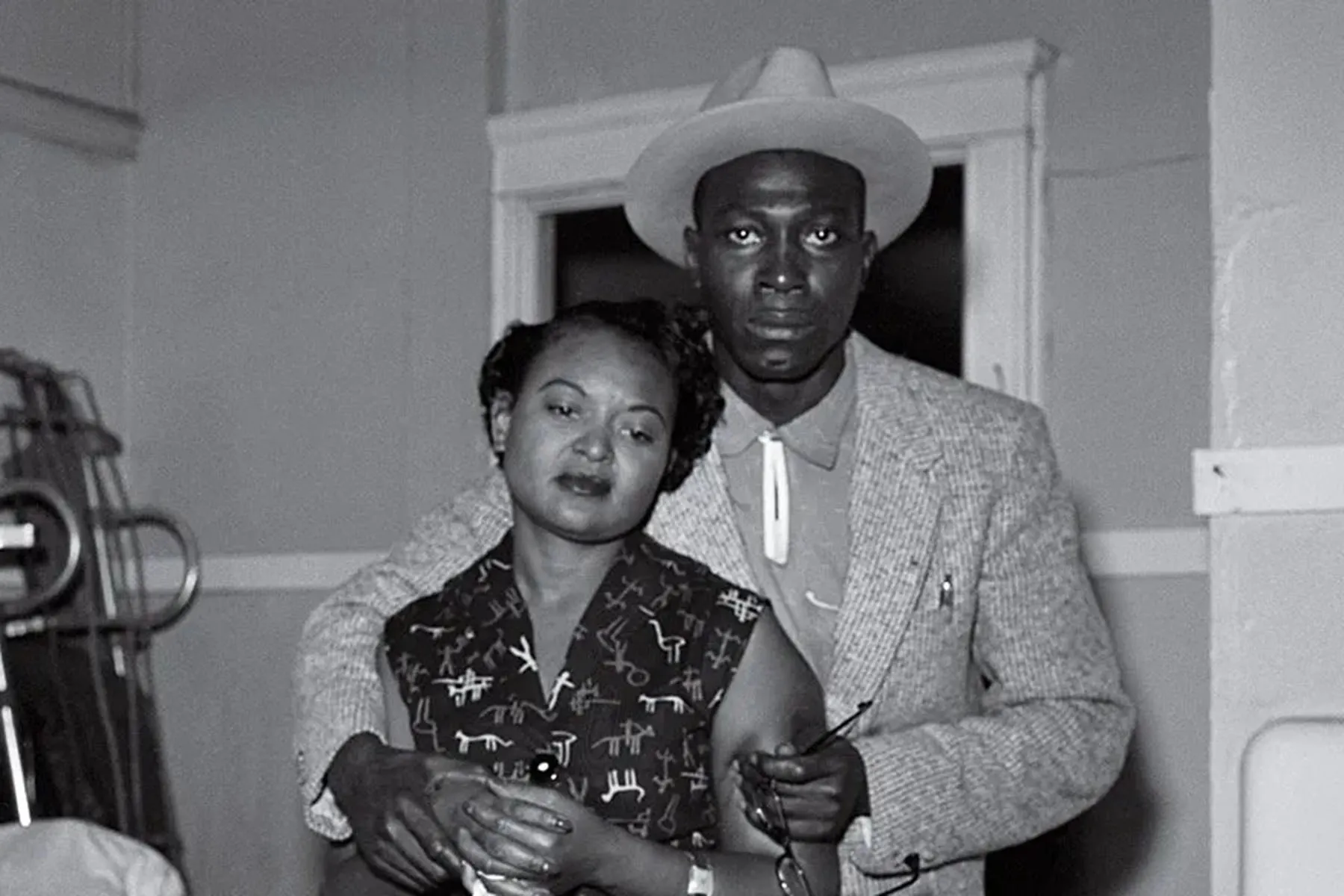

In August 1955, Till had barely turned 14 when he visited his Mississippi relatives from Chicago, only to be beaten and shot to death after he reportedly wolf-whistled at Donham at a store in Money.

His mother decided to leave the casket open to “let the world see what they did to my boy.” More than 50,000 attended the funeral, and the photograph of his brutalized body appeared in Jet and other publications around the world.

An all-White jury acquitted Donham’s then-husband, Roy Bryant, and his half-brother J.W. Milam, only for them to confess later to Look magazine they had indeed beaten and killed Till.

The injustice made international headlines and fueled the civil rights movement. Four days after Rosa Parks heard a talk about Till, she boarded a city bus in Montgomery and refused to give up her seat. She was later quoted as saying she thought about Till the whole time.

Donham had long insisted on her innocence in Till’s murder, repeating that assertion in her unpublished memoir, “I Am More Than a Wolf Whistle,” but civil rights activists and others have called for her prosecution, accusing her of identifying Till to the killers.

After an intensive FBI investigation, a majority-Black Mississippi grand jury declined to indict her in 2007. Last year, another grand jury voted against indicting her.

The memoir remains sealed in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill until 2036. But through a source, the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, now part of Mississippi Today, has obtained a copy of that single-spaced, 109-page memoir, which contradicts her original statement to her husband’s defense lawyer, Sidney Carlton.

In that original statement, Donham said when Bryant brought Till to her, he “was scared but hadn’t been harmed. He didn’t say anything. Roy asked if that was the same one, and I told him it was not the one who had insulted me.”

That is far different from her memoir, which portrays Till as fearless and her as frightened. After she denied Till was the one at the store, she claimed he “flashed me a strange smile and said, ‘Yes, it was me,’ or something to that effect. … He didn’t act … scared in the least.”

Davis Houck, co-author of “Emmett Till and the Mississippi Press,” said Donham’s claim sounds like it was ripped from William Bradford Huie’s lie-filled Look article, which depicted Till as fearless to the end.

“The idea that Till would essentially out himself in front of his kidnappers and would-be killers,” he said, “is beyond absurd.”

Dale Killinger, who as an FBI agent investigated the Till case, said Donham’s claim in her memoir contradicts what she told him in 2005 — that Till said nothing when his kidnappers brought him to her.

During his investigation, he took the statements of two Black men. The first had been confronted by Bryant, who accused him of insulting Donham. She intervened and said it wasn’t him, and Bryant let him go.

The second man was walking home from Money after buying molasses for his mother, only to be picked up by Bryant and his half-brother, J.W. Milam. The man quoted Donham as saying, “That’s not the n—–! That’s not the one.”

The man said he was tossed from the truck and lost his front teeth when he hit the ground.

Those statements dovetail with the testimony of Till’s uncle, Moses Wright, who said Milam told him, “If this is not the right boy, then we are going to bring him back. If it is not the right boy, we are going to bring him back and put him in the bed.”

As Milam and Bryant left, Wright said they asked someone in the vehicle if this was the boy and that a voice replied, “Yes.”

“Was that a man’s voice or a lady’s voice you heard?” the prosecutor asked.

“It seemed like it was a lighter voice than a man’s,” replied Wright, who later told his son, Simeon, it was a woman’s voice.

Killinger said he believes that Donham escaped justice.

“She should have faced a jury on manslaughter charges,” he said. “Under Mississippi law, if you did or said something, knowing that someone might be harmed, and your statements or actions led to them dying, you would be subject to manslaughter charges.”

Informed of Donham’s death, Keith Beauchamp, whose documentary on Till played a role in the FBI’s reopening of the case in 2004, said, “Damn, damn, damn.”

Since 1955, law enforcement and local officials have allowed Donham to evade justice “without answering to her participation in the kidnapping that led to the lynching of Emmett Louis Till,” he said. “The good old American judicial system has failed us yet again. Now Carolyn Bryant Donham will face her maker.”

Houck said Donham’s passing closes a long chapter that began in the early 2000s to prosecute those involved in the kidnapping and murder of Emmett Till.

“Despite efforts from the Department of Justice, the FBI, local prosecutors in Mississippi and private citizens,” he said, “she was never arrested or indicted for her role in one of the 20th century’s most infamous lynchings, this despite the fact that Leflore County Sheriff George Smith had issued a warrant for her arrest days after Till had gone missing from his great aunt and uncle’s home in Money, Mississippi.”

In her memoir, Donham wrote that she did not wish Till any harm and that those responsible for his murder should have been held accountable.

“His death was tragic and uncalled for beyond all doubt,” she wrote. “For that, I am truly sorry. If it had been within my power to change his fate, I would have done so.”

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.