Your trusted source for contextualizing the news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

The 1959 Broadway debut of “A Raisin in the Sun” brought America inside a crowded Chicago apartment where the dreams of Black families went to die.

And while Lorraine Hansberry was making history as the first Black woman to have a play produced on Broadway, she and her family back in Chicago were embroiled in a fight that reflected the role of racism in both her life and the conditions creating the conflict of her play.

The play follows the Youngers, a family of five jam-packed into a kitchenette apartment in Chicago’s Black Belt. Crushed under the weight of racism, they dream about how the $10,000 life insurance check left to them upon their patriarch’s death could improve their destitute living conditions.

During the play’s yearlong run, Lorraine and five family members sought to reinstate a $1 million lawsuit they had filed in 1958 against the city of Chicago, then-Mayor Richard J. Daley and other city officials who they said utilized “unreasonable and capricious mass inspections” and abused state power to strip them of the properties left to the family by Carl Hansberry Sr., Lorraine’s father, when he died more than a decade earlier. Researchers have not been able to obtain paperwork from the city of Chicago detailing the outcome of the 1958 lawsuit, so it’s unclear how it ended.

Now, Lorraine’s sister Mamie Hansberry and grandniece Taye Hansberry are calling for reparations — not only in the form of monetary restitution for the properties, but also in the reclamation of their patriarch’s legacy.

Taye said that her great-grandfather worked hard to build the generational wealth that would allow her aunt, the playwright, to pursue her passion in New York. When he died in 1946, he left behind a real estate business. But in the decades following his death, the family lost much of his fortune to policies that they believe were racist in their application, such as urban renewal and eminent domain.

“Nobody was given anything. It was worked for,” Taye Hansberry told The 19th. “Are we not afforded the American dream that everybody else is?”

The Hansberrys are working with nonprofit organization Where is My Land, founded by Kavon Ward, who led the charge to return Bruce’s Beach to the Bruce family in Manhattan Beach, California, after city officials fraudulently condemned and seized it from the Black family in the 1920s. The organization has several open petitions for Black families looking to reclaim properties stripped away from them by racist policies.

“Not only are you stealing my land, you’re stealing my opportunity to pass down generational wealth. You’re stealing my opportunity to use the equity to build more, to buy more. And you’re putting me in a position where I’m vulnerable to poverty and my kids are vulnerable to poverty,” Ward said, explaining the harms she is seeking to repair.

“How can you level the playing field at this point? At this juncture, equality is not enough. Equity is.”

After the successful return of Bruce’s Beach in July 2022, Ward said about 250 people reached out to her asking for help to reclaim their family’s land across the United States, the Hansberrys among them.

Ward declined to discuss the strategy her organization will take with the Hansberry family. She did not specify an amount of money or whether there were any specific properties the family would pursue.

“What I can say is we will be evaluating and assessing whether it makes sense to go about this legislatively, legally, or legislatively and legally,” she said. “We’re going to be pursuing justice around this by any means necessary.”

In her previous case in California, Ward held a Juneteenth ceremony on Bruce’s Beach to raise awareness and circulated a petition demanding that the state return the land to the Bruce family and pay restitution. Legislators subsequently passed a bill to remove restrictions on the property so it could be returned.

“My goal is not to snatch away people’s property. But there has to be some type of righting the wrongs that happened to my family and other families. Let’s try to make these wrongs right and keep these things well documented in history books so the past does not repeat itself,” Taye Hansberry said.

The Hansberry family’s call for reparations joins a growing chorus across the nation: Nearby Evanston, Illinois, became the first U.S. city to grant reparations to Black residents in the form of a housing program. San Francisco is considering a proposal for reparations that includes a lump-sum payment of $5 million. And cities across the country including Memphis, Boston and New York have formed task forces to explore what it could look like if they paid Black people for the damages perpetuated by slavery and the remnants of its legacy.

The Hansberrys’ case for reparations interrogates the lasting effects of racism codified through policies like those that upheld segregation in Chicago’s urban renewal period.

Hansberry Sr. owned at least 10 properties on Chicago’s South Side by 1935, according to a research report by Where Is My Land. At the time, Black neighborhoods throughout the city were bursting at the seams as Black residents were restricted to certain areas while the population exploded.

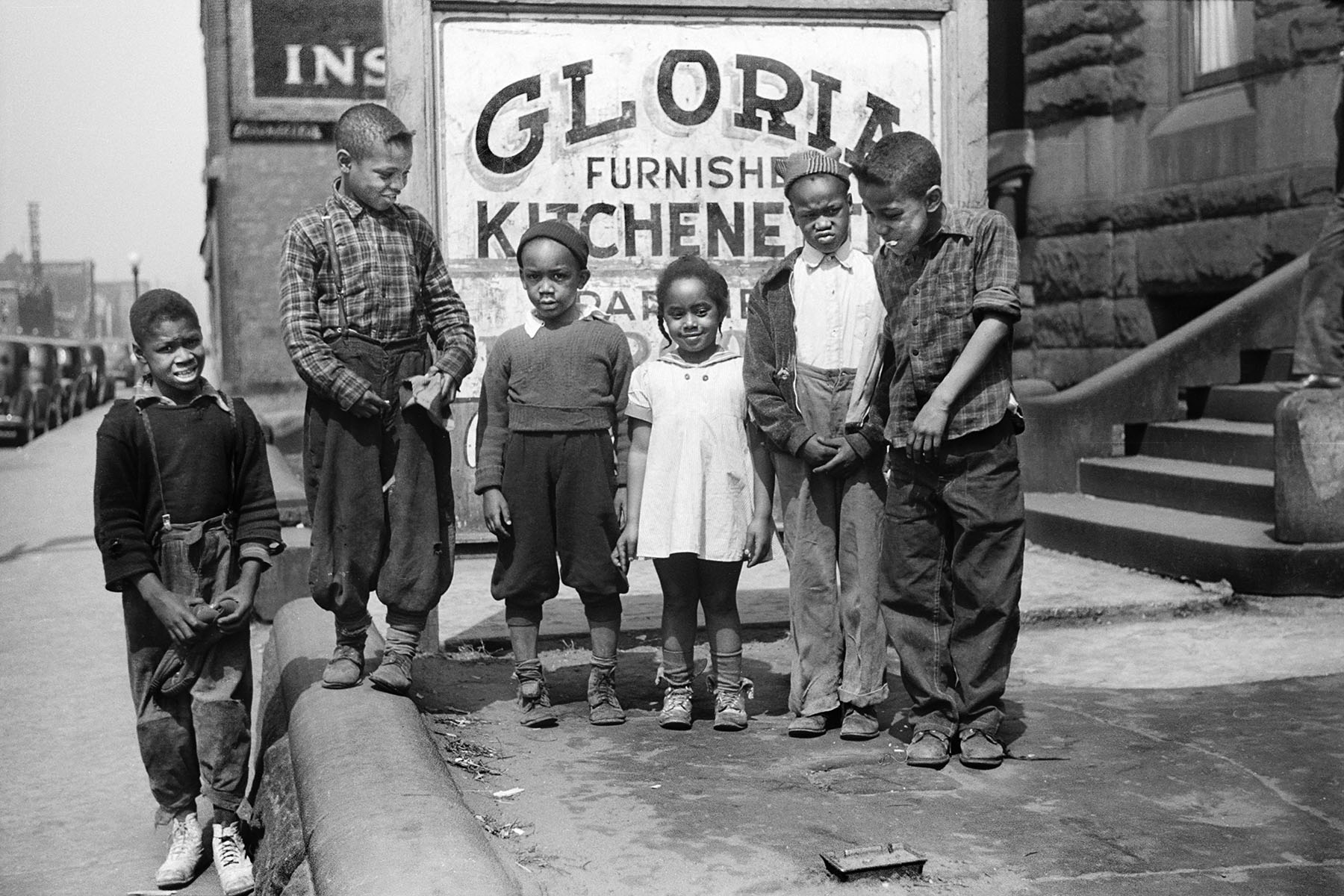

Between 1915 and 1970, during the Great Migration, millions of Black people left the South in droves for northern cities like Chicago to pursue better living conditions and job opportunities and to flee racial violence. The Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper founded by Robert Sengstacke Abbott, was an organ of the migration, urging Black families to leave the tobacco farms and blatant racial terror of the South for urban centers. The paper ran job ads in the classifieds section and reported on the success of migrants who left the South and made it to Chicago. Churches ran ads in the paper, welcoming southerners as new members. The paper also ran editorials with instructions on how to behave and dress in the North to orient the new residents.

A product of the Great Migration himself, Mississippi-born real estate broker Carl Hansberry Sr. was acutely aware of the wave of Black people flooding the city and its limited housing capacity, further compressed by segregation and racially restrictive covenants.

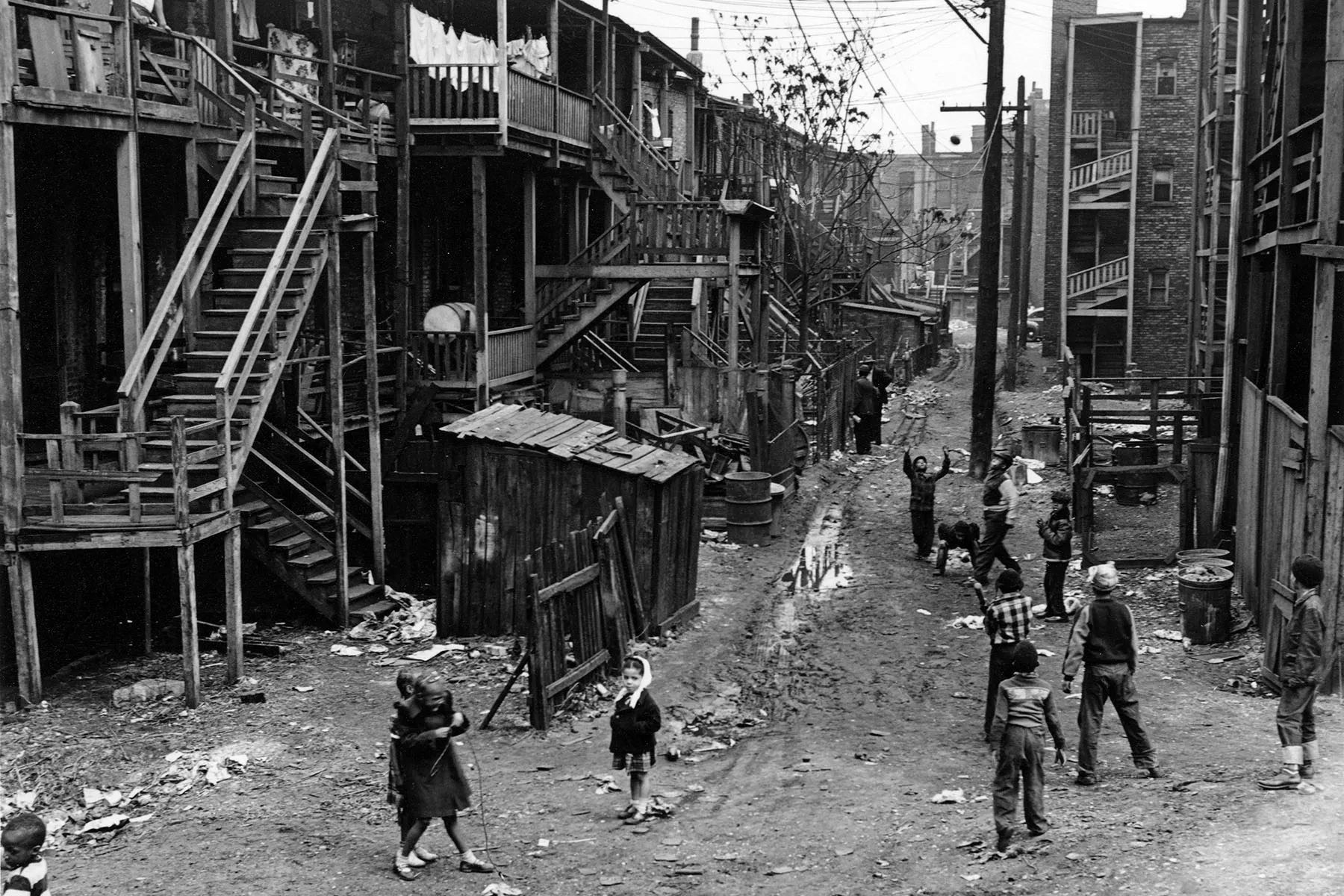

Black Chicagoans settled in parts of the city that came to be known as the Black Belt. The areas began to swell with the oppressive weight of racism, which confined millions of people to a narrow corridor of the city. They could not buy or rent outside of the Black Belt, and they paid much higher rents than any other group for substandard housing.

“These folks migrated up here thinking it was going to be a whole lot better. And they were met with discrimination. They were met with redlining, housing segregation, they were met with a lot of the same things,” Ward said.

Hansberry Sr. took on the fight against restrictive housing practices. In 1937, he purchased a home for his family in Woodlawn, what was then a White neighborhood. After the family moved in, a mob gathered outside the home. Someone threw a brick through a window, narrowly missing 7-year-old Lorraine’s head.

Anna Lee, a White neighbor, took the Hansberrys to court to push them out of the neighborhood. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in the Hansberrys’ favor based on a technicality. It ultimately did not take on racially restrictive covenants, but it did invalidate the covenant for the Woodlawn neighborhood. The decision enabled Chicago’s Black residents to expand eastward and made about 500 more homes available to them, according to a 1940 article in the Chicago Defender.

Hansberry Sr. wrote in the Chicago Defender, following the Supreme Court verdict, that he made the decision to move into Woodlawn as an effort to relieve the congested housing situation.

“I figured the most vulnerable spot to attack the restrictive covenants was where the pressure was the greatest,” he said. “Whenever the test comes, they actually lower property values, and the result is that the owners of property covered by covenants which comes within close proximity to the predominate colored area, find themselves with property on their hands which is no longer desirable to the better paying class of whites, and because of the covenants they are not available to the colored occupants.”

Hansberry Sr. also leveraged his career as a real estate broker. According to author Imani Perry in “Looking for Lorraine,” he would routinely purchase three-unit apartment buildings and divide them into 10 smaller units with partial kitchens attached to the living rooms. Multiple families would share a bathroom. It is that style of kitchenette housing that the family in his daughter’s Broadway play are crammed into.

By his death in 1946, Hansberry was a respected figure in his community for his dedication to civil rights. He was also disillusioned and considered moving his family to Mexico, where he died.

In the years following Carl Hansberry Sr.’s death, the city practiced what it called urban renewal, and what writer James Baldwin famously called “Negro removal.” With a slew of local, and then federal, legislation, about 50,000 families and 18,000 individuals were displaced between 1948 and 1963.

“The legal framework for the national urban renewal effort was forged in the heat generated by the racial struggles waged on Chicago’s South Side,” historian Arnold Hirsch wrote in his book “Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940-1960.” He described the city as “a persistent pioneer in developing concepts and devices that were later incorporated into the federal legislation defining the national renewal effort.”

Urban renewal legislation allowed for the expansion of the city’s power to use eminent domain to seize properties, permitted massive demolition and clearance of properties deemed slums and relocation for families affected by the renewal efforts.

But critics of urban renewal say the name is misleading.

Chicago journalist Mike Royko wrote that urban renewal was “the greatest deceit.” According to Royko, urban renewal during Richard J. Daley’s 21-year reign as mayor had wiped out housing for almost 30,000 low-income families, replacing it with only 11,000 units, most of which were expensive.

Instead of providing better conditions for those families living in neighborhoods deemed slums, the city pushed families to the margins, relegated them to public housing and erased their communities. Housing units like the ones Carl Hansberry Sr. created were razed or taken over by the city.

The urban renewal project began to take off nationally, as well. The 1954 federal Housing Act called for conservation of existing historical structures, building code enforcement and relocation of displaced families.

Building code enforcement came with fines that sometimes reached five figures. In 1960, the Hansberry family paid $22,122 in fines on 12 of their properties. Mamie Hansberry said that the family was often forced to pay the fines out of pocket, as they had a hard time getting banks to loan them the money for the barrage of repairs.

At the time of the Hansberrys’ 1958 lawsuit, the city was pursuing 42 municipal court cases against the family, according to the National Archives. The family had also evicted tenants from 50 apartments to begin renovations, but the Chicago building commissioner refused to give them a permit for the repairs. Allegedly, the building commissioner spoke abusively to Carl Hansberry Jr. and added numerous additional prerequisites for the permit.

Emmett J. Marshall, another Mississippi-born Chicagoan, described the city’s strategy to enforce urban renewal as “find violations or create some,” in a 1962 letter to the editor of the Chicago Defender.

His letter further describes two fates the Hansberry family, like many of the Black families of Chicago, faced both before and after the death of their patriarch.

“As soon as the black home seeker buys a home, one of two things is likely to happen. If he is in or near the suburbs he is likely to be greeted by a bomb-tossing mob, or, if he buys a home well within the confines of the black ghetto, and before his wife can decide in which room she would like to place the twin beds, the rumblings of a motor is heard; a look out the rear door will find a bulldozer has arrived, commanded by a wrecking crew. He may be stunned and dazed to learn that in the name of the much abused law of eminent domain this home too must go. The City, the County, or the State has just decided it needs a park, a playground, or some ‘open green space,’ and out of all the land the Good Lord made, only this spot will do.”

“Uprooted once again, the black home-seeker, trying to decide where now to buy, in his bewilderment must be ever mindful of the sad fact that if the bomb doesn’t get him the bulldozer will.”

Along with the reclamation of properties, a success for the Hansberry family would also reclaim the legacy of Carl Hansberry Sr. and his descendants, correcting the accounts that condemn him as a slumlord.

Official narratives perpetuated by Chicago’s local officials paint the family as slumlords. Alternate narratives, evidenced in the work of Black journalists at the time, paint Hansberry as a “race man,” who pushed back against oppressive rules.

“The late senior Hansberry, in addition to his real estate interests, was a militant fighter for civil rights who turned to politics as a way of campaigning against the second class citizenship of his race,” a 1960 article appearing in the Memphis World stated.

Along with his battle against restrictive covenants, he filed another lawsuit in 1938 against the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway for discrimination, alleging that they charged African Americans first-class fares, but relegated them to third-class passenger cars. The case was ultimately thrown out for lack of jurisdiction. Hansberry Sr. later printed a “know your rights” pamphlet for Black people riding the trains.

Through his lawsuits, business ventures and economic practices, Hansberry Sr. invested in the rights of Black people.

“You can tell throughout Carl’s work that he cared for Black people. He wouldn’t have endangered his family’s life if he didn’t. And the reason why he was under attack was because he was trying to fight against white supremacy and anti-Blackness,” Ward said.

After his Supreme Court win, Hansberry founded his own civil rights organization,

the National Negro Progress Association (NNPA), in 1941.

The NNPA focused on economics, aiming to strengthen and expand Black businesses and job opportunities through the creation of a $1 million fund to provide access to capital for businesses including lumber mills, wholesale stores, department stores and more. Along with supporting Black businesses monetarily, the group aimed to train Black business executives. The group also planned vocational training and rehabilitation for veterans returning from World War II.

“My great-grandfather was prominent and outspoken and built a really good fortune as a young Black man,” Taye Hansberry said. “He was also this really shrewd, intelligent, incredible businessman, father, husband, family man, who also produced one of the most iconic, not just Black writers in America, but writers in America, dare I say the world?’”

That is the legacy she wants to be remembered. And still, she wants restitution.

“I just want it to be clear that there is definitely a way forward and a happy ending for my family and other families without inflicting pain on to other people.”