In 2022, the American Library Association (ALA) recorded the most attempted book bans ever during its history of tracking censorship, and all of the 13 most-challenged books have one thing in common: They contain content deemed sexually explicit.

Last year, 2,571 unique titles were challenged, a spike from 1,858 in 2021, the ALA found. Forty-eight percent of these challenges originated in public libraries, 41 percent in school libraries, 10 percent in schools generally, and 1 percent in higher education libraries and other institutions.

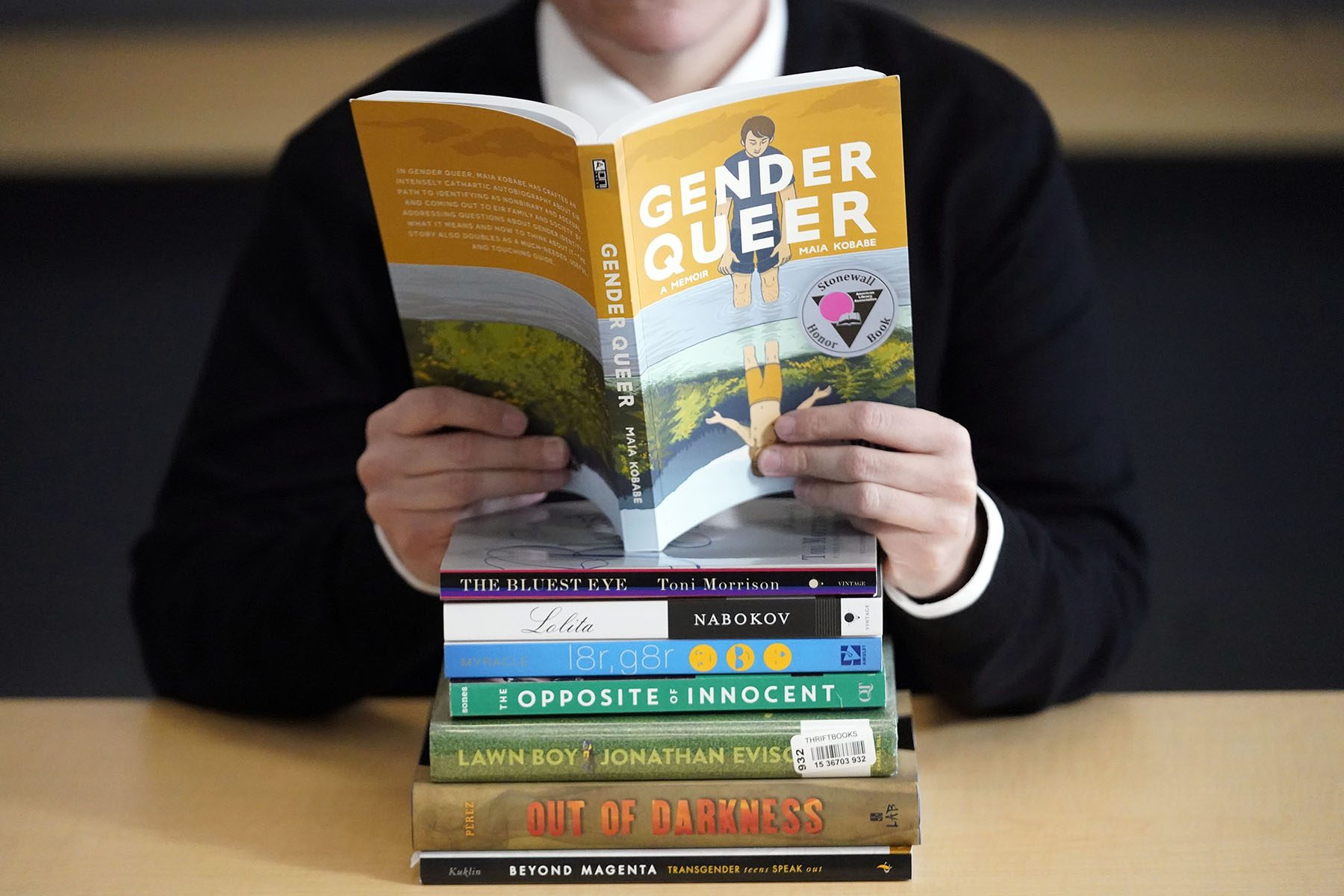

The newly released most-challenged list includes an eclectic mix of titles, many of which also appeared on the 2021 list. Among them are Maia Kobabe’s “Gender Queer” (2019), Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” (1970) and Sherman Alexie’s “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” (2007). Two books — Mike Curato’s “Flamer” (2020) and Sarah J. Maas’s “A Court of Mist and Fury” (2016) — debuted on the list the ALA’s Office of Intellectual Freedom has compiled for more than two decades to draw attention to censorship in libraries and schools. This year’s list reveals once again that books with LGBTQ+ subject matter are top targets of censorship, as seven of the titles address gender and/or sexual identity.

The rise in book bans stems from a movement by politicians and parents’ rights groups to restrict what students read, learn and discuss in school. The effort coincided with the COVID-19 crisis, the start of which forced classes to go virtual, resulting in heightened scrutiny of learning materials and schools becoming the epicenter of the nation’s culture wars.

Thirty percent of 2022 book challenges began with parents, 28 percent with library patrons, 17 percent with political or religious groups, 15 percent with school boards or administrators, 3 percent with librarians or teachers, 3 percent with elected officials, and 4 percent with other individuals. The ALA noted that the most-challenged list is not a complete picture of book censorship, as many cases of attempted bans are not reported to the organization or picked up by the press.

The 19th spoke with ALA President Lessa Kanani’opua Pelayo-Lozada about book banning over the past year. In addition to her role with the ALA, Pelayo-Lozada is the adult services assistant manager for the Palos Verdes Library District in Rolling Hills Estates, California.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Nadra Nittle: How is the 2022 most-challenged books list similar to the year prior?

Lessa Kanani’opua Pelayo-Lozada: Every year the American Library Association publishes the Top 10 most-challenged books of the year. The 2022 list has very similar themes, if not very similar titles, to 2021. Last year, the top books were “Gender Queer,” “Lawn Boy,” “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” “Out of Darkness” and “The Hate U Give.” Those were the top five. What we’re seeing are basically veiled attempts to challenge or restrict LGBTQ content and BIPOC stories under the guise of them being sexually explicit or anti-police or pushing a specific social agenda or moral agenda. Profanity, violence and drug use are also commonly [cited] in book challenges.

And books with sex scenes are now being deemed pornographic. What’s your response to that?

So there’s a very specific definition of pornographic that is used by the Supreme Court and is not covered in the First Amendment. The books that individuals are challenging — they are not taking those scenes into the context of the whole work. They are pulling out individual passages, so when taken into the large context of the actual work, it is not found to be pornographic.

Some of these books on the challenged list, such as “Gender Queer,” have ended up becoming bestsellers. Is that the silver lining here?

I think that [buying these books] is definitely a way to support the cause. I think we do have to be careful of some of the arguments like, “Oh, well, we don’t need it in a school library because somebody can just go by it.” Well, not everybody who needs access to that book can actually go buy it. It’s great for us to be able to bring more attention to these books for folks who may not have known that these types of books existed, but we also need to make sure that they are accessible to everyone.

While several books on the most-challenged list are recent, six were first published over a decade ago. Why do you think that is?

Book challenges are not new, right? We’ve always had book challenges. Books like “The Bluest Eye,” “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Of Mice and Men” — a lot of those have gone on and off the list over the 20-year history that we’ve been providing these lists. It’s often been for the same reasons. It’s just that now we’re seeing it at such a high level and the volume that we’re seeing makes it much more concerning and much more problematic because before it used to be one person would disagree with a book, and they’d be able to have a conversation with the library worker or the librarian or the school and be able to come to an agreement. But now, with these organized efforts, it’s just groups of people trying to silence the voices of many. So when we see these classic books on the list, it just reminds us sometimes of how far we haven’t actually come. Seeing the pushback against it now by the larger public — that’s kind of a hopeful point for me and a recognition that these classics will continue to be available.

The ALA has found that most parents oppose book bans, so why do they keep happening and what can parents do to prevent censorship?

So the reason that they keep happening is because often it’s not actually parents of the children who are in the schools who are going to these libraries that are challenging these books. It is individuals who are part of Moms for Liberty who are just filling out forms and making it seem like there is much more support for this than there actually is.

What parents need to do to be able to protect their family’s right to read is to write to their library directors, school librarians, principals and administrators, to let them know that they appreciate the variety of books in the library and the impact that the availability of those books have on their children, whether or not their children are reflected in the materials that they’re reading. That’s one way.

Another way that parents can help is to run for library and school boards, to be that voice of reason on the board and to not continue allowing the election of individuals who are not upholding their constitutional obligations to their communities when they are elected to these positions and are not coming at it with objective and fair points of views but are trying to push their own moral agendas. They can also buy these books, request these books from their libraries, check these books out of their libraries to make sure that it is being shown that the community wants and needs these kinds of materials.

Your one-year term as ALA president ends in June. What has the past year been like for you?

It’s been a really challenging year. I don’t think that this was the year that I anticipated my presidency being. I really thought that I would be able to focus on library workers and the state of library workers in a post-pandemic world and how we could really apply all of the lessons that we have learned during the pandemic to serving our communities better but, also, on a professional level, making sure that our library workers have the advocacy that they need. While we are still doing that, the main focus has become book bans and book challenges because, in 2022, we saw the highest number of book challenges that the American Library Association has ever seen since we started keeping track of book bans about 20 years ago. So that has been our primary focus — figuring out how to support library workers who are currently experiencing book challenges, who are experiencing actual physical threats and threats to their jobs and preparing those who haven’t yet received book challenges but likely will in the near future.

Can you elaborate on how librarians are being threatened?

In March, there was a bomb threat at a school library in New York [because the collection included “This Book Is Gay”]. There are librarians who have been doxxed. A librarian decided to fight back against groups that were slandering her name and trying to harm her character. There have been library workers who have had armed Proud Boys show up at their drag queen storytimes. Bullets have been found on library bookshelves. There have been very real, visible threats to library workers as well as the emotional and mental health toll that these kinds of things take on our library workers.

Have you seen any signs of hope?

I am ever an optimist. I’m always hopeful that we will get through this, but this is not a short-term fight. This is a long-term fight that we are in, and I just see things continuing to progress, especially as we’re entering an election year. Many politicians are using this as a political wedge and part of a platform for their campaigns. So what we really are emphasizing this year, and I think this is where my hope and optimism comes in, is when we are talking about how to get through this. Library workers cannot do it alone. We have to do it with the public and with those who also support the right to read, which is why we have a campaign called Unite Against Book Bans that provides people who maybe are not as entrenched in this work as we are with the tools to be able to write letters to their editor, to speak up at board meetings, to run for an elected office to be able to support library workers and schools that are going through these challenges.

You’re in Los Angeles County. California hasn’t passed statewide legislation to ban books, but bans have taken place at the local level. Have you observed this?

Yeah, absolutely. The thing about book challenges is it’s not just red states, right? It’s an everyone problem. The ALA polled voters in March of 2022 to see who was against book challenges, and overwhelmingly, the voters who were interviewed — red, blue, conservative, Democrat, liberal, Republican — said that they were against book challenges in public libraries. So it’s an everyone problem.

Is there anything else you’d like to say about the ALA’s work during an era of unprecedented book bans?

One of the reasons I think that these politicians and these organizers are going for libraries right now is because we are trusted institutions in our communities. We, as library workers, often work and live in our same communities. We go to the grocery store; we go to the movies with these individuals. So, we know what our communities want. We have master’s degrees [that have taught us] how to curate and provide diverse collections for our communities that reflect all of the people in our communities, not just those who feel morally superior and who feel like their way is the right way. Many communities think that they’re homogenous, but they just create communities of fear where those who are different are not allowed to speak out. The library is there to truly be inclusive and be there for everyone. So, we continue to be trusted institutions, and we will not let those who think that they have power and control over us continue to dismantle public institutions and erase our community members.