For Women’s History Month, we’re letting women tell their stories in their own words through thoughtful conversations. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

In December 2020, Congress passed legislation enabling the creation of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum (SAWHM) to advance the understanding of women’s contributions throughout American history. An interactive website will precede the museum’s physical presence on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.; a timeline for opening will be set once the SAWHM’s site is officially designated.

In art museums across the United States, only 13 percent of the artists represented in collections are women. A recent study found that between 2008 and 2018, works by women constituted just 11 percent of acquisitions and 14 percent of exhibitions at 26 major American museums. The gender gap extends out of museums and into curricula too. In K-12 social studies curricula nationwide, only 178 women are individually named in state education standards nationwide; Only 15 of these women appear more than 10 times across states. Sixty-three percent of the women named in school state standards for social studies are White.

“As recent as this past year, a study of U.S. monuments across the country has noted that only 8 percent of all statues are actually dedicated to women — and that number includes mermaids and other mythical figures,” Lisa Sasaki, the interim director of the SAWHM, told the 19th. “If you take those kinds of mythical creatures out, that number drops to closer to 6 percent.”

Despite the absence of women’s presence in museums and the ways children learn history, people say they want to see more equality in gender representation — and parents most of all. A recent poll conducted by SAWHM sought to gain more information on what Americans are hoping to get from the American Women’s History Museum. Seventy-three percent of Americans said they would be very likely to visit a museum focused on American women’s history, with parents expressing particular interest: 83 percent of dads and 80 percent of moms said this was a kind of museum they would want to visit with their children. (There were not enough responses from non-binary parents for the results to be statistically significant.)

-

More from The 19th

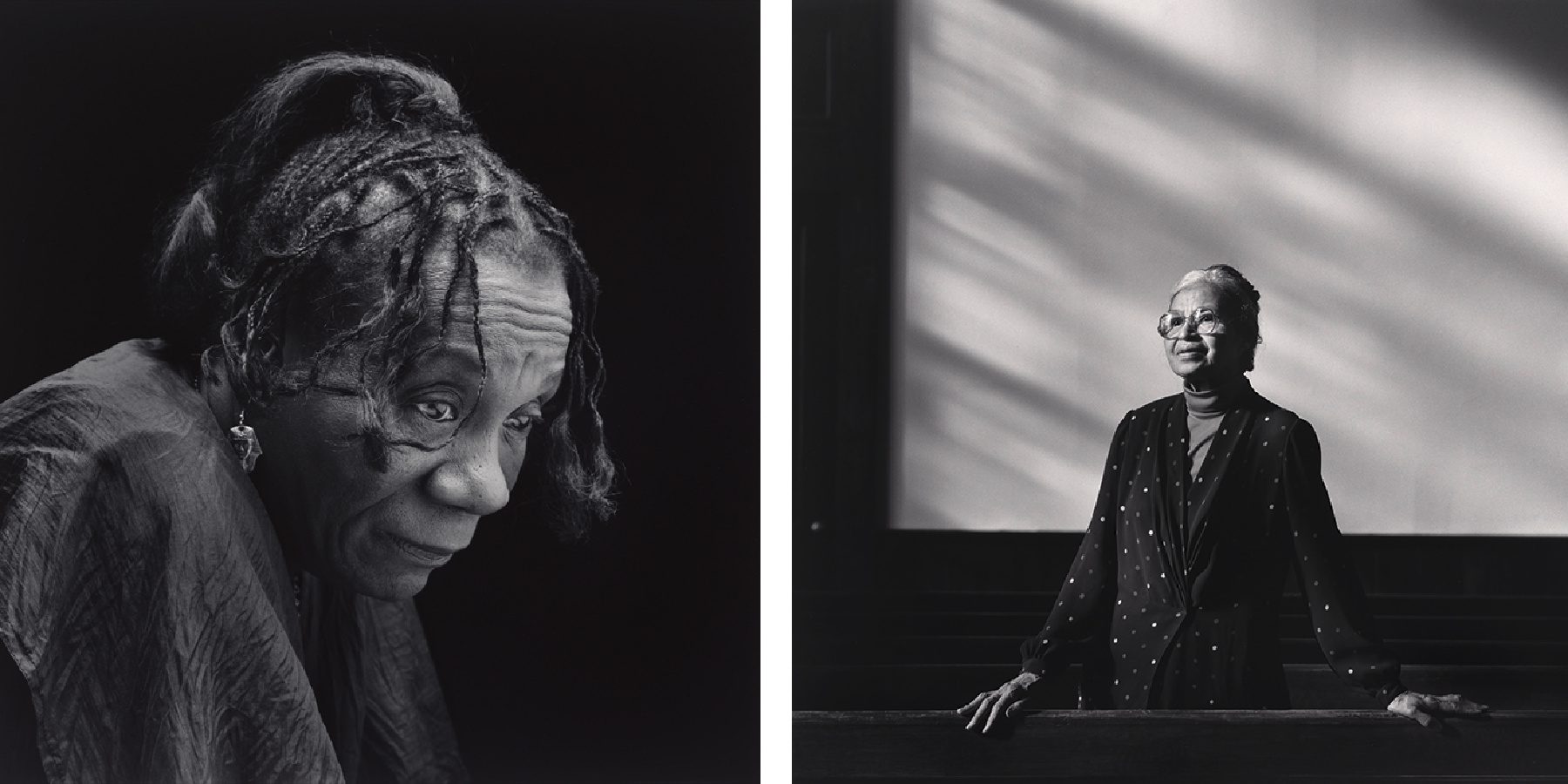

- ‘Moving unapologetically to the forefront’: How an archive is preserving the Black feminist movement

- Friends and mentees remember Judy Heumann, mother of the disability rights movement

- Barbara Johns made civil rights history at 16. Her sister reflects on the US Capitol statue planned in her honor.

Ahead of Women’s History Month, Sasaki spoke with The 19th about the museum’s goals and purpose, what the new SAWHM can do to change perceptions about women, and seeing yourself represented in museum spaces.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jennifer Gerson: How does this museum seek to address the holes in representation that exist when it comes to women and women’s stories?

Lisa Sasaki: Over 20 years ago now, groups of women really noticed the lack of stories being told about women, in particular in Washington, D.C., and, to be honest, nationally.

The National Mall in Washington, D.C., is a location that really tells America’s story, and the fact that women are not represented there is something that needs to be corrected. We’re very excited that Congress has asked us to work on this, to make strides in ensuring that this representation is there. That’s the reason why this is so important: Everybody knows how important it is to be able to see yourself within whatever it is that you’re doing, whether that’s within your own professional industry, whether that’s in history, whether that’s in the day-to-day of American society. It is so incredibly important to see your stories represented.

The place that we have to start off with is an understanding that American women’s stories are not monolithic. Unfortunately, many of the stories told about women today are really one-dimensional. They don’t allow for the many roles, experiences and backgrounds that women have held. We haven’t really allowed for those experiences to be highlighted and explored. So what this museum aims to do is to change that and to tell a multitude of stories through various mediums.

How are you thinking about intersectionality in your approach to telling the stories of American women right now and throughout history?

We have 20 other museums and nine research centers that are all across multiple disciplines, focusing on many different areas. I like to start there by answering why the Smithsonian is the right home for this kind of museum. This facility is so well-positioned to be able to tell this range of stories through these intersectional lenses because we have amazing colleagues in the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the National Museum of the American Latino, the Asian Pacific American Center — as well as places like the Air and Space Museum, the Natural History Museum, the American History Museum.

You start to see this wide range of expertise that we can call upon, and while we are very excited to tell these stories within the context of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum, there are also stories that will be told throughout all of these museums. I think that really adds to our ability to bring people together to learn more about these different aspects of American women’s history. The Smithsonian overall is committed to presenting multiple perspectives that really address the complexity of women’s history in America, and we’re really excited to be able to lead the scholarship to ensure that our exhibitions, our programs and our educational materials not only reflect an inclusive history but an accurate one. Our content aims to reflect the historic contributions of all Americans, today and throughout history.

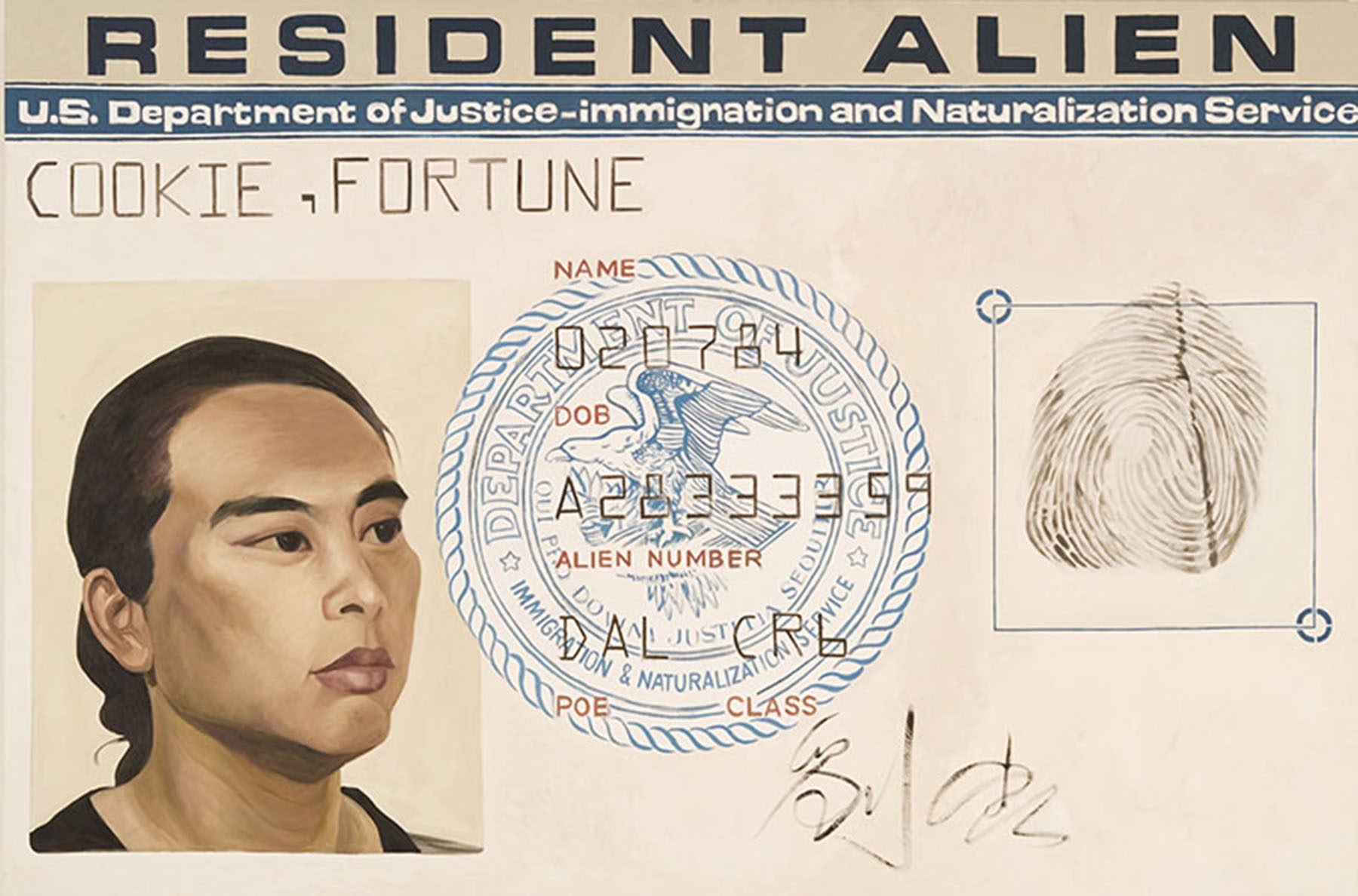

How are you thinking about the framework created by a museum devoted to American women’s history and how it relates to transgender women and people outside of the gender binary?

There’s this larger conversation around gender happening that is incredibly complex, and I think we need to be aware that that complexity exists and that it needs to be examined just as much as the complexity that exists around race. It’s a kind of complexity that comes with a lot of different viewpoints, that defies a singular definition of things. One of the things that I think that the Smithsonian does really well is exploring those kinds of complexities.

In this particular case, the Smithsonian as an institution will be looking now to examine the complexities around gender, and within that, the museum is committed to providing the most inclusive way of approaching this topic. As I mentioned, this is about all American women. What we are not wanting to do here is create some artificial definition of what it means to be a woman, but rather to explore the many, many different aspects of that.

What are you hearing from focus groups about what Americans are really hoping to see in this kind of museum, and how are you thinking about how you can meet people where they are?

There’s a tremendous amount of interest in this topic. Seventy-three percent of people surveyed said they had interest in visiting a museum dedicated to American women’s stories.

We are so excited to hear from people and gather their stories. Our research has shown us that the majority of people say they would be interested in sharing their own stories and experiences with us. But an interesting fact that we dug into a little deeper is that the number of women declined slightly when it comes to interest in sharing personal stories, and we were really curious about that.

We dug into that through focus groups. Interestingly enough, we found that those women weren’t saying that they were no longer interested in sharing their stories, but that over time, they felt that their stories just wouldn’t be of interest, that they hadn’t done anything in their lives that maybe would warrant them sharing their stories.

We would like to change that opinion. We want everybody to feel that their stories are valuable and important. It was really startling to me, this idea that women had a decreased desire to tell their own stories, not because they didn’t have a story to share but because they didn’t think that others would be interested in hearing it. I think we see this attitude reflected in so many areas when it comes to whose history ultimately gets told.

This is really notable when you search in archives around the country — you’re just not seeing archives from women. Part of the reason for that, that many historians and archivists have found in their work, is that women just don’t think that their materials are important enough, that their stories aren’t important enough to warrant being preserved. I think that’s something that really needs to be changed.

What kinds of stories will be highlighted by the museum to help change this idea that everyday women don’t belong in museums? In thinking about the collection, how do you hope to think about display and exhibition creation and the mediums utilized in combating the internalized idea felt by so many women that maybe their lives, experiences and objects aren’t “important” enough to be put on display?

We’ve already started to do that through our website, womenshistory.si.edu. We have had curators from our American Women’s History Museum embedded in museums across the Smithsonian network as part of a pan-institutional initiative, doing research on the other museums’ collections and sharing stories.

One fabulous example that has come up was a story from the Natural History Museum, of a woman who had been cataloging different types of grasses and became the definitive expert on different expert on types of grasses and other botanicals around the world — and was also a suffragist. That’s someone whose work is behind the scenes who you wouldn’t know about but who is so important.

We also found the story of one of the Smithsonian scientists whose study of feathers was instrumental to the design of planes being able to fly more safely. There are all examples that we have, that you can now do a deep-dive on and learn more about these women and their work and histories through the content on our website.

How can a museum, and this museum in particular, engage in the work of combatting that idea that has been internalized by so many women: that their stories are not important, that their daily lives are not important, that their work is not important, that their domestic lives aren’t something significant or worthy of being preserved?

Fundamentally, in our philosophy, how we begin to address this is helping people to understand that this museum is not going to be a Hall of Fame. We already have one of those, and they do an amazing job of presenting what I like to call “the firsts.” It’s of course important to see representation of women of high distinction, but I think what’s even more important to see than the first is maybe the 71st or the 101st.

It’s so important to see all of the women out there that have quietly helped change perceptions around who women are — that is what allows different generations to have a different understanding today of what women can do. I grew up at a time when I was still hearing things like, “Women can’t be firefighters. Women can’t be jet pilots. Women can’t be race car drivers.” We see today that of course that has changed, see generations who have seen those limitations opened up — but I still think that there are so many barriers that continue to exist, that might be a little bit more hidden. It is so important to recognize women’s achievements in the home alongside their achievements made within their professional fields.

We have to combat this idea that women are only worthy of being studied or preserved in history if there’s some kind of first.