We’re answering the “how” and “why” of politics news. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

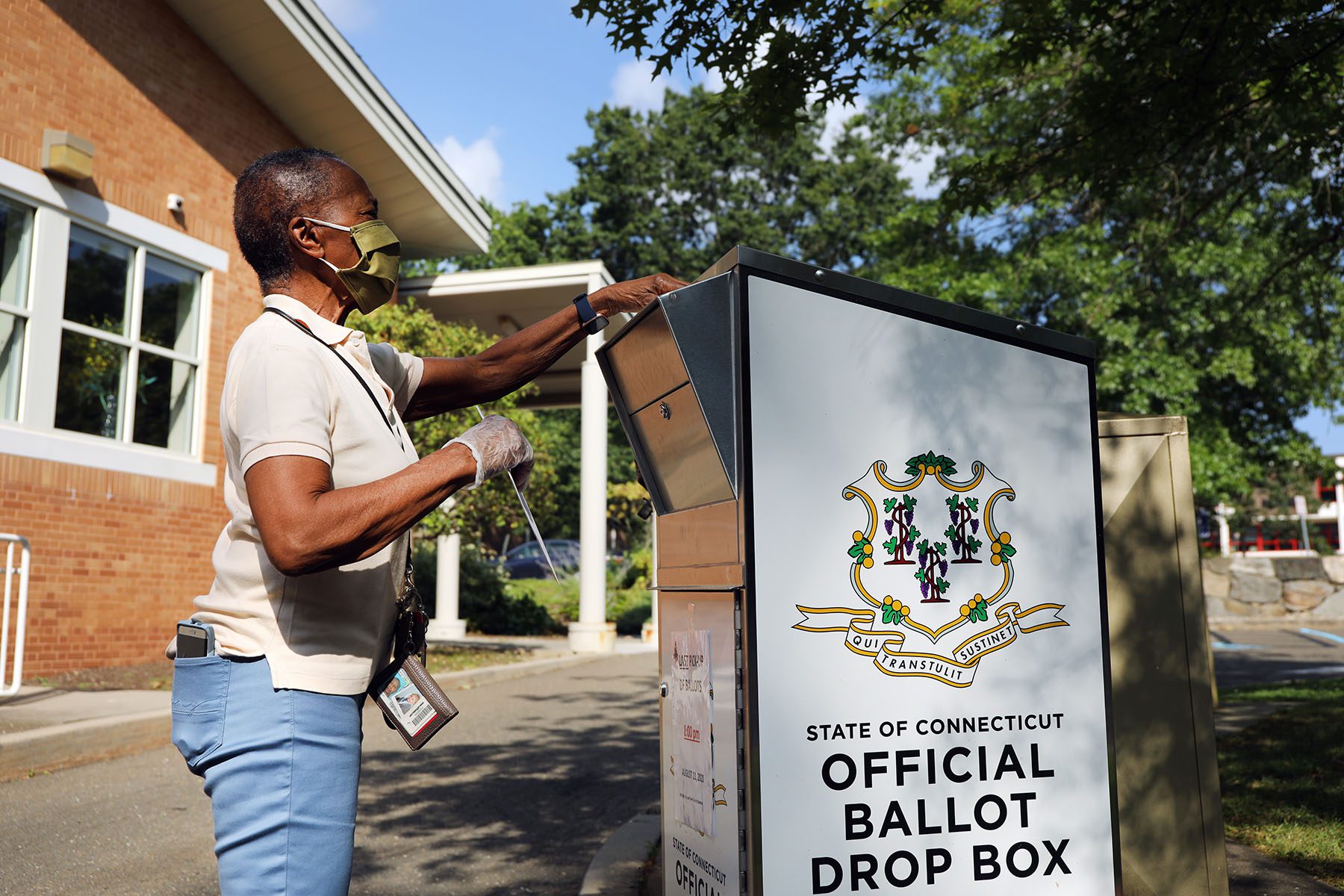

Last November, Connecticut voters made two choices with big implications for how they vote in future elections: They approved a ballot measure to institute early voting, and they elected Stephanie Thomas as their next secretary of state.

Thomas, a Democrat and former state lawmaker who campaigned on expanding voting access, defeated Republican Dominic Rapini, who questioned the 2020 election results and claimed without proof that voter fraud is rampant. In the process, Thomas made history as the first Black person to be elected to the post, which Connecticut officially calls secretary of the state.

Now part of Thomas’ job will be to figure out how to actually implement early voting and get Connecticut off the dwindling list of states without it (leaving just Alabama, Mississippi and New Hampshire). Early voting has been linked to increased turnout for women voters — advocates say it helps caregivers and people who work nontraditional hours, who are disproportionately likely to be women, and all voters from marginalized communities, who may face more barriers with long lines on Election Day.

So far, several competing ideas are floating around the Democratic-controlled legislature, which will have the final say on a bill. The cost of enacting early voting could also be a major factor in negotiations.

While Thomas will not determine what happens, she hopes to play a role in the legislative process. As the former vice chair of a key elections committee, she wants to use her experience at the statehouse to maintain lines of communication with policymakers who will finalize a proposal before it goes to Democratic Gov. Ned Lamont, who previously expressed support for the ballot measure.

“In terms of ballot access, early voting is certainly the number one priority,” Thomas told The 19th.

The early voting proposals in the legislature range from a few days’ length to 14 days. Thomas has expressed support for 10 days of early voting, including two full weekends and flexible hours.

“The number of days is almost one of the least relevant parameters, in my opinion,” she said. “Meaning, if you had seven days, 24 hours — that might be better than 30 days, two hours a day.”

Thomas added: “Very much part of my role is to think about implementation, and what our office can and can’t do and in what time frame — and to make sure that I assess [the legislature’s] priorities correctly and roll out everything in due course. But you can’t always do every single thing at once.”

Patricia Rossi is vice president for advocacy and public affairs for the League of Women Voters (LWV) of Connecticut, which advocated heavily for the early voting ballot measure. She said determining the quality of Connecticut’s early voting will come down to state funding and its ripple effect on polling locations, hours of operation, staffing and other resources.

“Budget is going to be a big issue for anybody who wants to implement early voting,” Rossi said.

Most voting rights advocates also agree that some of the state’s election equipment needs to be updated soon. Thomas has indicated that will be a priority for her as well, and estimated a roughly $25 million price tag to updating the state’s tabulators, which is machinery that helps record election results. (Thomas declined to estimate the cost of early voting without a formalized plan yet from the legislature.)

Rossi said Thomas has met with the LWV and other voting rights groups to discuss priorities for early voting. Rossi said no matter what Thomas does, it will be a lot of juggling.

“The secretary of state has a lot to accomplish in her first year in the post, but we know that she is as firm of a supporter of early voting as we are. And she is as firm of a supporter of voter education as we are,” she said.

Jess Zaccagnino, policy counsel for the ACLU of Connecticut, also wants any early voting plan that considers hours, number of polling locations, and accessibility for the elderly and people with disabilities.

The group supports at least 14 days, with at least one Saturday and one Sunday. She said the group would back even more, noting that 23 is the average number of early voting days in the other 46 states that allow it. Policymakers including Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy also want more days.

More women registered voters have turned out to vote in states with in-person early voting, according to a data analysis by Voting Rights Lab, a nonpartisan organization that tracks voting legislation.

“It hurts working people to not have flexible hours,” said Zaccagnino. “We have to make sure that the actual locations, the polling sites, are equitable and distributed well across the state.”

The ACLU and the LWV are also backing a state-level voting rights bill to protect against voting discrimination. The policy is a state version of the federal John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act that has stalled in Congress. Thomas recently attended a news conference on the policy proposal. There are also efforts in the legislature this year to get another ballot measure to voters that would allow for no-excuse absentee voting.

“We really have the opportunity to make this a session of voting rights,” said Zaccagnino.

Semedrian Smith, deputy executive director for the Democratic Association of Secretaries of State, said the pandemic and 2020 election created a surge in expanded options for voting in states led by both Democrats and Republicans. Now more legislatures are stepping in to make some of these changes permanent.

“We’re seeing these wonderful success stories come through and voters using their voice at the ballot box and clearly demonstrating that they are supportive of pro-democracy initiatives and processes,” she said.

Thomas said whatever advances, it should include a budget that allows for early voting this fall, before the 2024 presidential election, in order to give election workers time to address any issues that come with new rules. Connecticut has 169 municipalities that make up its cities and towns. Nearly half have just one polling location because of population size.

“If we try to pass along the cost to each individual town, it will not have the intended benefits that we would like to see,” she said.

Lamont shared a budget proposal publicly this month that did not include money for early voting. But as one of the first steps in the process, it doesn’t necessarily mean lawmakers won’t attach state money in the end.

Zaccagnino said she was disappointed that early voting was not spelled out in Lamont’s budget. But she hopes upcoming budget hearings will recognize that state funding has to be a part of the equation.

“The governor and the legislature both need to demonstrate that they value democracy and the will of people by fully funding early voting,” she said.

Thomas added that it’s important for the public to remember that voters have a voice in the process in the weeks ahead. She described her office as “one cog in the wheel” that includes other policymakers and real people.

“The people have a real opportunity to help shape what this looks like through the public hearing process, whether they show up in person to testify or submit something in writing,” she said. “For me, this just reminds me that civic engagement is the most important tool that we have in this representative democracy … so I hope we will also hear from [voters] as we decide how it’s shaped.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article said Thomas was formerly the chair of a legislative elections committee; she was vice chair.