Cathy Darling Allen is extra busy right now.

For weeks, she has been preparing to administer elections in Shasta County, a rural conservative community in northern California. But in between ordering ballots and making calls to a hierarchy of election workers, the county clerk and registrar of voters has also been fighting disinformation about the integrity of elections, in an office that she has helped lead for nearly 20 years.

In early October, Darling Allen scheduled a virtual webinar to share facts about the county’s handling of elections, an event in response to disinformation being shared. Weeks earlier, an election denier visited Shasta County and spread debunked election conspiracy theories.

Darling Allen said she would have preferred to use these critical final weeks to better prepare for the logistics of early voting, which kicked off in the state on October 10. Already, some issues have emerged: Her office recently acknowledged an error on ballots in a city of about 6,000 voters, prompting plans for a special election that will cost at least several thousands of dollars.

Darling Allen called the incident “a simple human error” that was exacerbated by the extra time and resources spent addressing conspiracy theories and responding to several records requests by people looking for proof of nefarious activity. The same week Darling Allen’s office was double-checking ballots, she had to attend a meeting over unfounded speculation about the primary election results, she said.

“I absolutely attribute it to the environment in which we’re all working in,” she told The 19th.

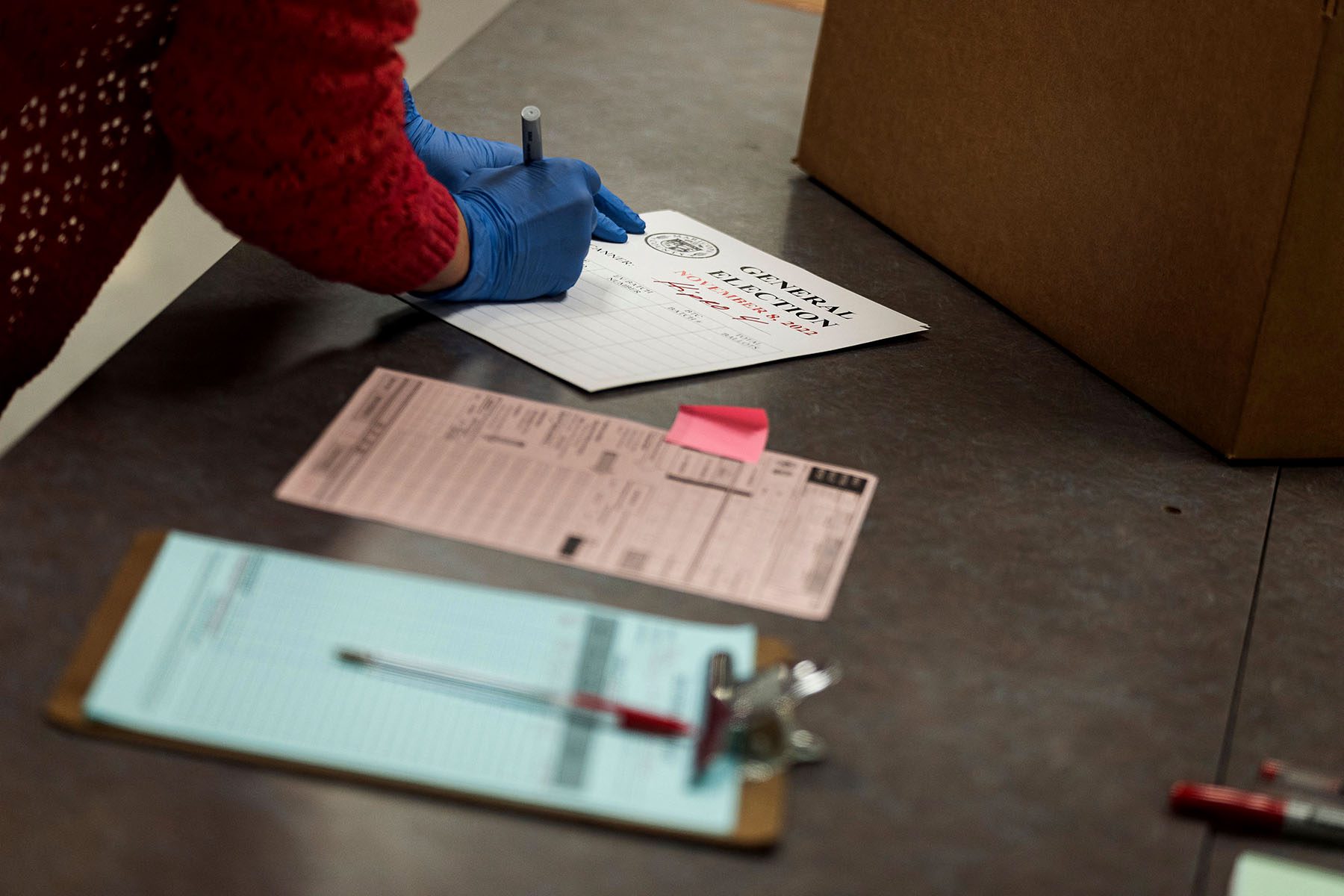

With a week to go before this year’s midterm elections, election workers — a predominantly women-led workforce — are on the front lines of administering early voting around the country. At least 24 million people have cast an early ballot as of Tuesday, according to the University of Florida’s U.S. Elections Project.

So far, the election has been mostly functioning as it should, according to interviews with administrators in several states. Ballots are getting mailed out on time, and voters are getting them back either through the mail, dropboxes or in person.

“Administrative-wise, elections are going like normal,” said Carly Koppes, the Weld County clerk and recorder in northern Colorado. “It’s just all the extra stuff.”

The “extra stuff” is the ongoing effects of the 2020 election, when people including former President Donald Trump lied about widespread fraudulent results despite no proof. While some people have stepped down as election workers in part because of related harassment, the ones left are trying to do their jobs amid unfounded public skepticism. Election workers are still handling phone calls and emails from the public that continue to promote conspiracy theories about elections. It’s too soon to know what that will mean for Election Day voting, but it continues to take up their time.

On the same day that she was ensuring ballots were being distributed for early voting, Koppes called a local radio host to address some misinformation about ballots that was being shared on the program.

“Trying to address the questions and the concerns and get the correct information out there is very, very challenging,” she said. “And it is a seven-days-a-week kind of responsibility.”

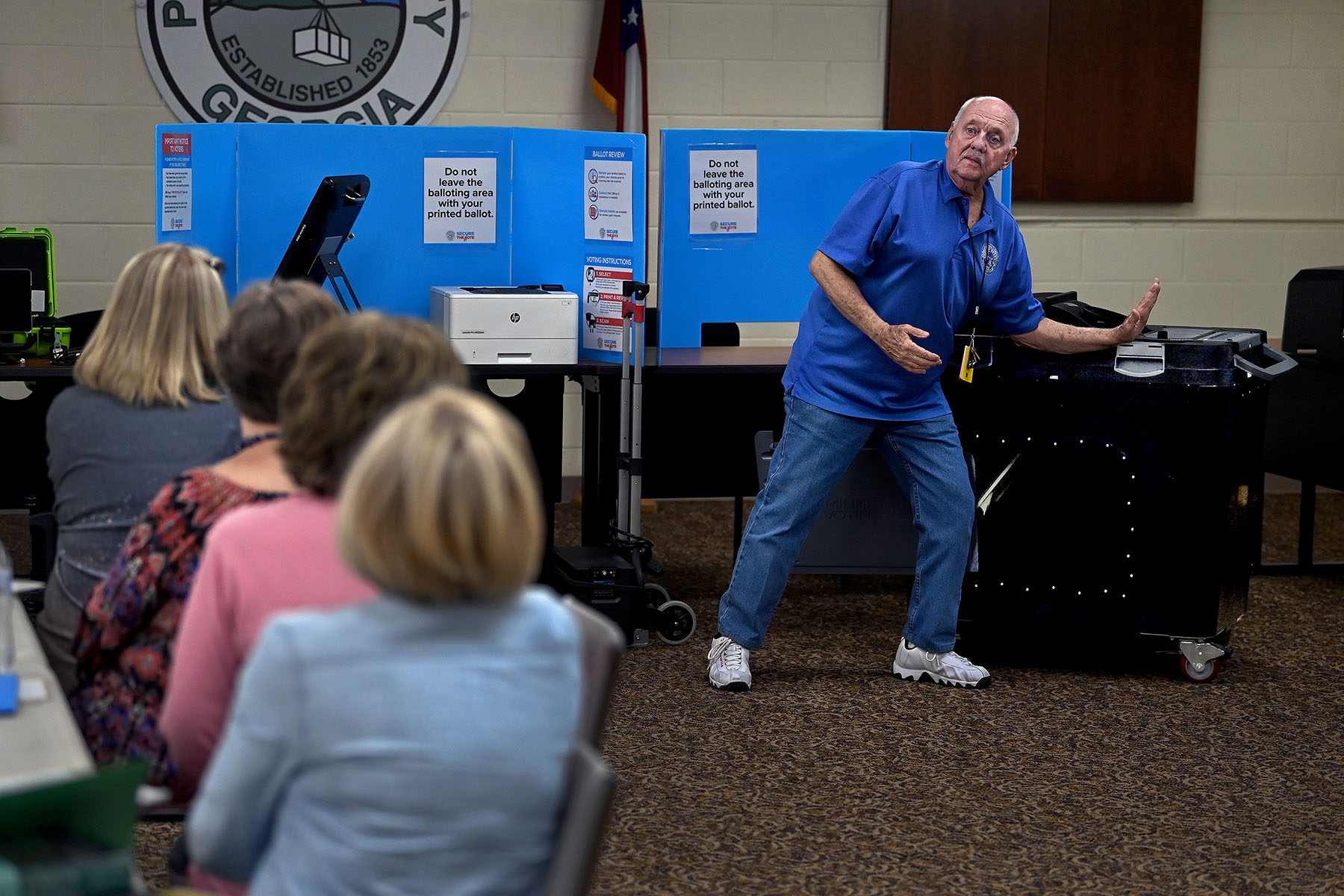

Signs of tension have popped up around the country over the past few months: In Georgia, where a record two million voters are expected to cast ballots ahead of Election Day, individuals and groups for weeks have filed mass challenges to voter registrations, mostly in Atlanta-area counties with large populations of people of color. Election officials have dismissed most of the challenges so far, but a new state law allows for ongoing challenges to pop up.

In Nevada, officials in rural Nye County announced plans this year to hand count election results to address unfounded concerns — a process that can be prone to human error. A state supreme court ruling in late October temporarily put it on hold.

In Arizona, reports emerged of masked and armed individuals intimidating people who were trying to leave ballots at dropboxes in the populous Phoenix area. The Arizona secretary of state’s office has referred some of those cases to law enforcement. On Friday, a federal judge appointed by Trump said barring some of those watchers could violate their constitutional rights.

Hannah Fried, executive director of All Voting is Local, a nonpartisan organization that works to protect voting access, is tracking reports of voting issues in eight states: Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. Her group is also responding to the developments in Arizona by ensuring people know how to report instances of voter intimidation. But she expressed relief that voter intimidation is not more widespread so far. She noted that’s because elections have guardrails.

“The environment of running elections is not a free-for-all,” she said. “And certainly in the last couple of years, states and counties have taken steps to shore up resources and bolster infrastructure that we have to better protect election workers.”

Fried said the days of election workers working quietly behind the scenes has changed since lies about the 2020 election have permeated public perception. The 2020 election is considered the most secure to date.

“This is an important moment to check in. How are they feeling? What is happening for them?” she said. “Bottom line, most election officials are just trying to do their job and do it well.”

Still, it’s still too early to know what conspiracy theories and misperceptions will mean for ballot counting, processing and certification. More than 100 lawsuits have been filed that challenge everything from mail voting to absentee ballots ahead of the midterms, according to The Associated Press. Some states have rules in place that mean vote-counting can take several days or even weeks after Election Day; while a delay in results is not unusual, voting rights groups worry it also has the potential to spark new falsehoods.

Politico has reported efforts that appear underway for conspiracy theorists to encourage poll challengers or watchers — a short-term job during an election, where people with partisan affiliations can monitor and report voting activity — to file complaints to challenge election outcomes in the midterm election.

Barb Byrum oversees elections in Ingham County, a Michigan community that includes Lansing. The former Democratic lawmaker said more organizations have signed up this year as “challengers” who are able to monitor the election.

“I am hopeful that these challengers are being properly trained by the organizations, that they may only make good-faith challenges, and if they disrupt the election process, they will be held accountable,” she said. “So the concern is, if a challenger disrupts the Election Day polling location, they could slow down the process. Slowing down the process could cause lines. Lines could cause someone to opt not to exercise their right to vote.”

This year, candidates running for positions up and down the ballot have said they believe the country’s decentralized election system is rigged. Those people are now seeking office in local and state roles that involve overseeing those same elections, raising the specter of future threats to election integrity from the people who are supposed to ensure it.

Byrum said nearly two dozen of her fellow county clerk colleagues have opted recently not to run for reelection or have resigned or retired early.

“It is unfortunate that through the attacks, the harassment and everything that election professionals have been experiencing over the past few years, that they’re leaving. And that’s very concerning to me,” she said. “Because not only are they taking all that knowledge, but in some cases they’re being replaced by the same people who have been attacking these professionals.”

Fried said it’s important for voters to remember that there are systems in place to address alleged bad actors.

“The message for voters, but also frankly the people who would intimidate them, is that, if you think that you can just roll up and do and say whatever you want to voters to get whatever political outcome you’re seeking, that is not how our system works,” she said. “And there are laws that will stop you from doing that. There are government officials who will take their responsibilities seriously to protect voters. That is the thing that I really want voters to know, that that system is there to have their back.”

In October, Attorney General Merrick Garland said the U.S. Justice Department “will not permit voters to be intimidated” during the midterms.

Byrum said she is not going anywhere. But she said the constant drum of speculation of her work is “death by a thousand cuts.”

“There is a lot going on. That’s usually the case for an election. I mean, elections are never a one-day event and it’s never a quiet time. But it just feels like there are more pulls on my time, and more pulls on resources.”

Darling Allen, who was reelected as county clerk over the summer, also vowed to continue the work. But she had a warning.

“It’s really not a reasonable thing to expect humans to work incessantly for years at higher stress levels without showing some cracks,” she said.