The Supreme Court’s conservative majority has overturned Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 decision that guaranteed the right to an abortion, in a 6-3 decision. The court also overturned Planned Parenthood v. Casey, a 1992 case that in some ways weakened Roe but maintained its foundational abortion rights protection.

But the six justices who agreed to strike down abortion rights in the case known as Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization are starkly divided in terms of what that decision will mean for other major civil rights: the right to contraception, marriage equality and interracial marriage, to name a few.

Since May 2, when Politico published a leaked draft of the opinion, many had speculated that the court’s decision to overturn Roe could lead to the inevitable destruction of those other protections. The right to an abortion is based in part on the same constitutional principles as those other civil rights protections, a notion known as substantive due process.

Both the final decision and the draft opinion compared the Roe decision to cases such as Obergefell v. Hodges, which guaranteed the right to marriage equality; Loving v. Virginia, which protected interracial marriage; Griswold v. Connecticut, which established the right for married couples to use contraception; and Lawrence v. Texas, which prohibited states from banning sexual relations between people of the same sex.

But the court’s final decision and its three concurrences — authored by Justices Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts, respectively — show a court that is, at the very least, not fully united on how to approach other rights now considered sacrosanct by many Americans. And it shows further fissures in how the court’s conservatives will approach future questions of abortion rights.

The final decision is very similar to the draft opinion. It retains its citations of the much-criticized 17th-century English legal scholar Matthew Hale, who is responsible for the so-called “marital rape” exemption. It also retains inflammatory language such as the word “abortionist,” a term that historically referred to people who helped perform illegal abortions in non-medical settings, and is now used by abortion rights opponents to deride the physicians who help terminate pregnancies.

In its main opinion, authored by Justice Samuel Alito, the court’s majority went out of its way to argue that the right to an abortion is fundamentally different from other rights. Striking down the right to an abortion, the majority argued at multiple points, does not mean the court will also necessarily eliminate other protections — though it did not argue that the court will maintain those rights if they are in fact challenged. (Alito dissented in Obergefell, the most recent of those cases to be decided. And in her 2020 confirmation hearings, Justice Amy Coney Barrett famously refused to answer whether Griswold had been correctly decided.)

-

Read Next:

“Rights regarding contraception and same-sex relationships are inherently different from the right to abortion because the latter (as we have stressed) uniquely involves what Roe and Casey termed ‘potential life,’” the decision reads. “Therefore, a right to abortion cannot be justified by a purported analogy to the rights recognized in those other cases or by ‘appeals to a broader right to autonomy.’ It is hard to see how we could be clearer.”

But separate writings reveal that not all the court’s conservatives agree.

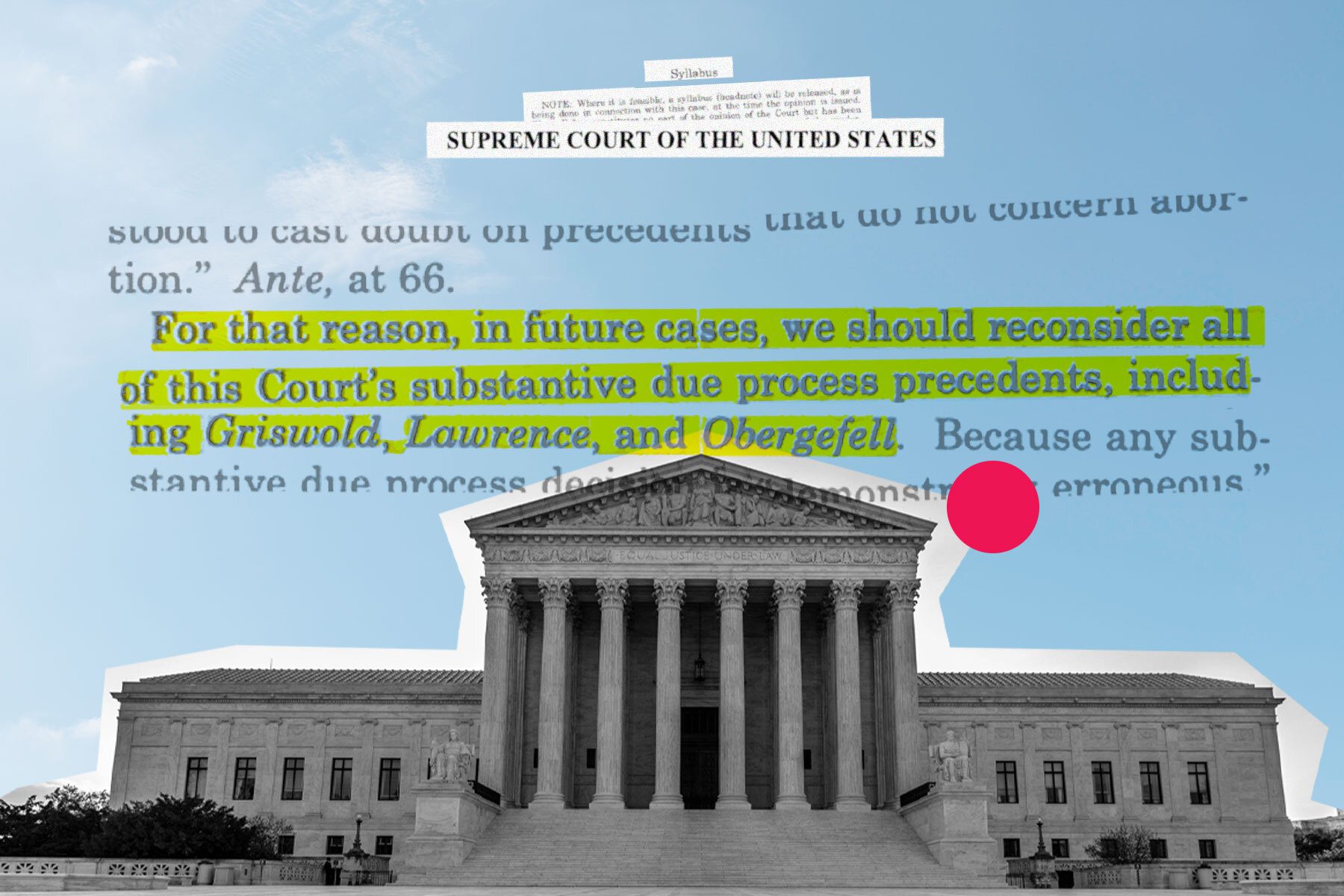

In a concurring opinion, Thomas argued that while he agreed with the rationale to overturn Roe, he also embraces a legal theory that strikes down other protections as well. At play is a legal notion called “substantive due process” — the idea that the Constitution’s due process protections extend to protecting other basic rights as well. That notion is the basis for many court decisions enshrining civil rights not explicitly enumerated in the Constitution.

The court’s majority opinion does not weigh in on the question of whether the Constitution does in fact guarantee the right to “substantive due process.” But in his concurring opinion, Thomas argued that the principle should ultimately be discarded — and the cases relying on that principle reconsidered.

Though the court did not weigh in on cases such as Griswold, Loving, Obergfell or Lawrence, Thomas suggested that Friday’s ruling should result in it revisiting and likely overturning those cases as well.

“We should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell,” Thomas wrote. “Because any substantive due process decision is ‘demonstrably erroneous,’ we have a duty to ‘correct the error’ established in those precedents.”

In their dissent, the court’s three liberal justices made a similar point, also suggesting that the end of Roe will ultimately result in a court undoing those other protections. It is not clear yet if any cases challenging those protections are in the works or might make their way to the high court in the coming years.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who had been considered by some to be a potential swing vote in this decision, embraced the court’s reasoning in his concurring opinion. He did not weigh in on how this decision affects other rights, or on whether the idea of substantive due process should be preserved. Instead, his writing sought to cast the Dobbs decision as a move to weaken the court’s influence and return power to the states.

“To be sure, this Court has held that the Constitution protects unenumerated rights that are deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition, and implicit in the concept of ordered liberty,” Kavanaugh wrote. “But a right to abortion is not deeply rooted in American history and tradition, as the Court today thoroughly explains.”

Kavanaugh also argued that it is not clear how the court will weigh in on future questions of abortion rights. But he suggested that he would not endorse a state trying to, for instance, prohibit its residents from seeking abortions in other states if they cannot legally access one at home. Lawmakers in some states, such as Missouri and Louisiana, have already considered legislation that would do precisely that.

With Roe overturned, 13 states have laws on the books that would ban virtually all abortions. In three states, those laws take effect immediately. Others will require some action from their state governments, and others will take 30 days to kick in. Still more states have laws banning abortion as early as six weeks into pregnancy, and governments in a handful of states are expected to soon pass legislation restricting access.