In 2020, a viral photo taken at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, pointed to the enduring invisibility of women of color in the climate movement. Vanessa Nakate, a Black Ugandan climate activist, had posed for a photo with other notable climate activists, all White women, only to be cropped out of the final version that was widely shared by The Associated Press.

Like Greta Thunberg, who was also in the picture, Nakate had become famous for embarking on her own solitary strike, hers in front of the Parliament of Uganda to protest climate inaction. She had also founded her own youth climate organization and was invited to speak at COP25, a conference where global leaders convene to discuss climate change. But in an instant she — along with her climate work — was erased.

“You didn’t just erase a photo,” she later tweeted about the incident. “You erased a continent.”

AP’s executive editor publicly apologized to Nakate. Her image soon made its way to another important platform: Wikipedia. It was added by Afrocrowd, a nonprofit that seeks to add more people of African descent to Wikipedia, which remains one of the top visited websites in the world.

While uploading a photo may seem like a small act, it’s part of a broader effort to utilize Wikipedia’s anyone-can-edit model to write people back into society’s historical and ongoing story. In this way, recognition is being given where it’s due, changing how society collectively views different identities, professions and regions of the world. This year, digital activists are using it to write women and LGBTQ+ people back into climate work.

“It impacts who is recognized as being an expert, who is recognized for their achievements, and it’s also a passive way to change the face of science,” said Farah Qaiser, who is on the leadership team of 500 Women Scientists, a nonprofit that aims to close the gender gap in the field and online. “So often women and other marginalized scientists aren’t recognized or overlooked for their achievements. So with Wikipedia editing, we’re rewriting women and other marginalized groups back into history.”

Women make up less than 19 percent of all biographies on Wikipedia. But in recent years, several digital activist groups have formed to tackle the issue. This year, one such group, Women in Red — composed of a group of editors aimed at turning Wikipedia’s red links, meaning there isn’t an active article page, to blue “live” links — is focusing its year-long initiative on adding more women to climate-related entries. Collectively organizations are chipping away at the invisibility of women, women of color and LGTBQ+ people, and they’re doing it one editor, one biography and one image at a time.

Rosie Stephenson-Goodknight, the cofounder of Women in Red, a volunteer-run initiative, has been writing Wikipedia entries since 2007. Initially her focus wasn’t on gender. She wrote about whatever fascinated her at the time. “I just enjoyed the research and the writing,” she said. “I enjoyed working towards this common goal of the sum of all notable human knowledge.”

But over the years she became more aware of the lack of entries about women. So she started writing them herself — to date she’s written over 1700. It’s a task made difficult by the dearth of information about many women on the internet.

“Men’s biographies are low-hanging fruit. There’s so much information out there. They’re easy to write,” she said. Women’s biographies, on the other hand? “There’s so much less.”

That information is important because in order for a biography to qualify for Wikipedia, it needs to meet what is known as a “notability” criteria. That usually has to be proven by using other citable sources from the internet, things like accolades and awards, New York Times obituaries and media articles.

“Wikipedia can only really reflect those sources and society at large,” Qaiser said. She continued: “It’s easier to sit down and create and edit pages, but dismantling all those broader systemic inequities? Well, that’s a forever problem.”

Writing women and LGBTQ+ people back into history, particularly in the climate sphere, is challenging for reasons outside of what information is available on the internet. If Wikipedia is, at its purest, a reflection of bias in society then there are a whole host of reasons why there aren’t more women or LGBTQ+ climate scientists to begin with.

“The systemic inequities that exist in the broader world are also impacting who even qualifies and meets the notability criteria,” said Qaiser.

For example, a 2019 survey about gender bias by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a global consortium that produces climate assessments which are authored by hundreds of scientists, found that more than a third of those surveyed said they felt men authors dominated discussions in their working groups. Furthermore, 38 percent of women said they saw someone else take credit for a woman’s idea and nearly twice as many women as men cited child care responsibilities as getting in the way of participating in the IPCC.

Globally, just 30 percent of science researchers are women, according to UNESCO, and when women do successfully ascend the ranks, their contributions to science receive less credit than men, and they are less likely to be nominated for awards than men. Other studies have shown that women are also less likely to be quoted than men in science reporting.

All these factors play a role in who meets the notability criteria for the website. It’s why Qaiser, who has hosted over a dozen events known as edit-a-thons, which are focused on bringing together new and old editors alike to add women and LGBTQ+ biographies on Wikipedia, co-wrote a column in Nature in May listing ways academic institutions could help fight the gender bias on Wikipedia. The piece suggested asking university media departments to write more articles about women’s achievements, which could provide some of the factual heft needed to bolster a notability argument, and asking institutions to provide photos that can be used on Wikipedia.

“If we’re going to write these biographies, we can’t write them if society doesn’t provide us with content,” Stephenson-Goodnight said.

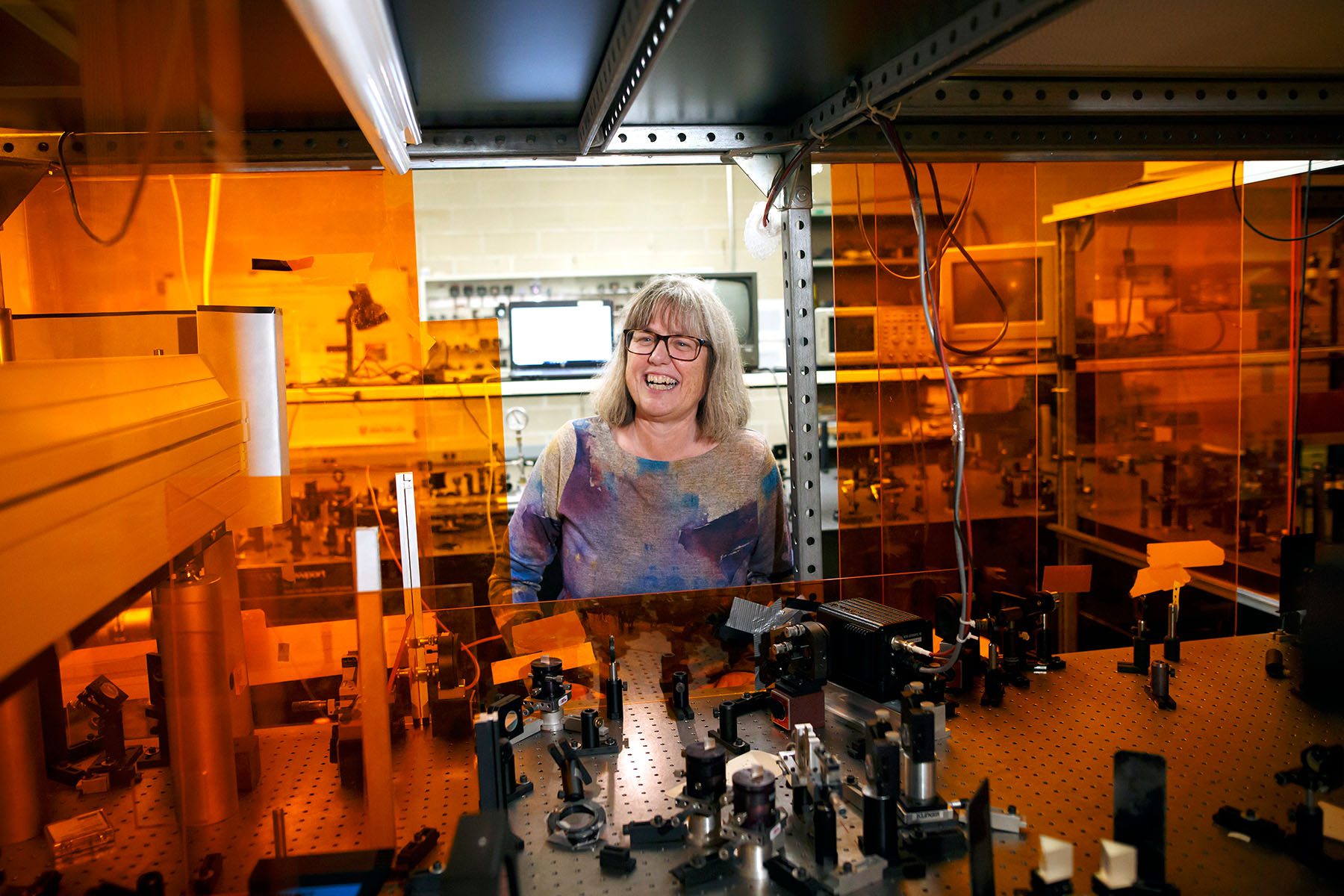

Even then, it’s not always enough. Famously, Donna Strickland, a Canadian physicist, had her biography nominated for deletion by an editor years earlier for not meeting the notability requirement. After a user submitted a new biography, that submission was also rejected. A few months later, she went on to win the Nobel Prize in physics.

She was already the past president of the Optical Society (now Optica), a leading scientific organization, among other accolades that would qualify as “notable,” Stephenson-Goodnight said. “If Donna Strickland had been a 59-year-old man, instead of a 59-year-old woman, would her biography when it was first written … been promoted to be in Wikipedia?” she said. “We’ll never know.”

A study published last year found that women’s biographies were more often nominated for deletion than biographies written about men. (Most of Wikipedia is written and edited by men — they make up approximately 85 percent of contributors.)

Of the women biographies that do make it through the deletion gauntlet, many do not have images. Only 20 percent of images that include people, found in Wikimedia Commons, depict women, said Mariana Fossatti, the decolonizing Wikipedia coordinator for the global nonprofit Whose Knowledge. The organization focuses on bolstering the online representation of marginalized communities, which Fossatti pointed out makes up the majority of the global population.

Fossatti, who is based in Uruguay, said that increasing representation on Wikipedia also increased visibility on other content providers like Google, which pulls from the site. “So if you have inequalities and a colonial perspective biasing Wikipedia, that bias spreads across the internet.”

Currently Wikipedia is heavily skewed toward Western thought and history because a majority of editors are White men based in the global North, she said. “We know that knowledge is based on the long history of colonization.”

It points to the importance of Nakate’s case, Fossatti said. Her deletion from that photo taken at the World Economic Forum “is a symptom of what is happening with climate change [work],” Fossatti said, “[where] young Black and brown people from the global South are unknown or invisible.”

But unlike historical archives of the past, there is a potential for Wikipedia to be more inclusive and reflective of society.

“If people can find a representation of say a nurse or a librarian or a doctor or software engineer and that person, that face, is a woman, or a woman from Latin America, for instance, that makes a lot of difference,” Fossatti said.