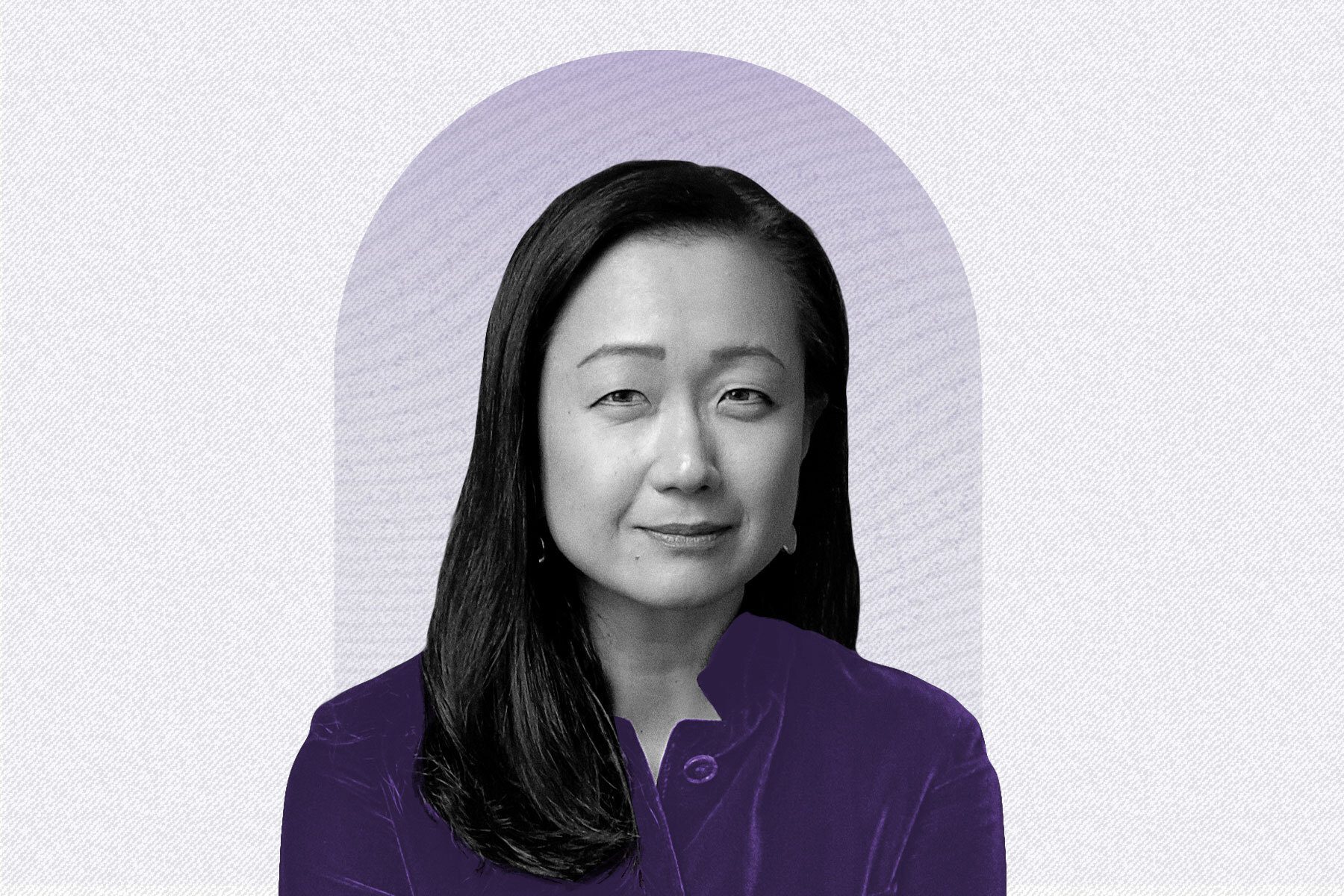

Min Jin Lee’s novels tell the stories of women at specific moments in time, both historically and personally. The common thread in all of her work is how characters come to see themselves and understand how gender serves as an intermediary tool within larger social transactions of power. As a popular, critically acclaimed author and public figure, Lee regularly writes about her experiences as a Korean American, immigrant, woman and artist and her opinions on current events tend to deeply affect readers of many differently held identities.

For Asian-American and Pacific Islander Heritage month, Lee — whose novel Pachinko was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2017, and has been adapted into a streaming series that just had its finale on Apple TV — spoke with The 19th about how she thinks about the intersections of gender, power, politics and the way we live now as we lean into our own identities and stake them out in our own communities, online, in real life, and on the page.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jennifer Gerson: It’s the start of AAPI Heritage Month in the year 2022 — what does that mean right now? AAPI people have historically been through so much in this country, so what does celebrating this month look like given that history in America?

Min Jin Lee: Thank you for recognizing the context of that. The context is really the most important thing about Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians, who are in this incredibly huge tent of what we call “Asian Americans.” And because it’s such a huge tent, we have such a varying history. We also have many individuals in this tent who aren’t even aware that there is “a month.”

I also want to include those who are LGBTQI as well as trans folks and adoptees. I also think about multiracial people right now and that’s really exciting to think about including them as such. [All of these groups] have been excluded traditionally from this tent, and I want to say, “Come on in! Let’s party!”

I could complain and say, “No, May is not enough.” But instead, I think we should start with the fact that there is a May and there is a movement, and it is important and growing.

It feels like your voice has become the front one of this movement of Asian and Asian-American writers who are saying, “Yes we are writers and our work needs to be evaluated as such — but have you heard about these other things happening in the world?” How does gender intersect with this dynamic?

I have been so profoundly influenced by the feminists that I’ve studied with, namely bell hooks, and then all the writers that she introduced me to as a student. And I think that the work that Kimberlé Crenshaw and Tarana Burke have done recently really influenced me as a woman and as a woman of color.

I’m a global feminist, as a mere matter of fact. In the same way that I can’t leave my gender or my race at home, I don’t leave the world at home when I think about politics and the things that are going on in the United States. I’m American, but I’m also Korean-American. I’m also Asian-American, which is a political identity. So how can I forget Asia and how can I forget the plight of women in Asia when I speak about anything? When I think about the systems of patriarchy which are really limiting the choices of girls and women, I also think about how the role of gender is so culturally specific and changing.

Gen Z and millennials have taught us that gender fluidity is something that we all should really think about — and I think that’s a good thing! I want to really respect gender fluidity and I want to really respect gender specificity and culture.

What role do you think novelists have and need to have in reflecting back on the times we’re living through?

I believe that the novel can change the world.

This may seem completely preposterous, but I believe that storytelling is a powerful way of changing things. That whenever we have a great deal of information and are asking ourselves, “What do we do?” — this question is answered by trying to understand what happened. [We do that by] writing the story of what we think has happened.

My model of fiction has always been the 19th and early 20th-century social novels, because they’re novels of ideas. That’s the reason why I have to be in the world. I have to engage constantly and really listen to the changing tides. And then, my response to that has to be this final product of a story that I make from everything that I’m taking in.

I’m profoundly glad that millennials and Gen Z have twisted my ear and have served as my teachers because it’s their world right now. Boomers and Gen X? We are receding. We have to live in a way and produce things in a way that can be of service to the next generation.

Do you feel like there is a wave of progressivism that is happening in the world of writing and art that is in dialogue with what we’re seeing happen politically right now?

When I wrote and published my first novel, “Free Food for Millionaires,” it was 2007. It’s a novel about capitalism. And here’s a spoiler alert: My main character refuses to work in an investment bank. When it came out, many people said to me, “That’s a terrible ending! How could she choose to walk away from this kind of premium, white-collar job!” Recently there’s been this upsurge of interest in this book and now people are saying, “Oh of course the moral choice would be to honor her very rich creativity.” I think I’ve been trying to argue that for a very long time.

As for the work of my peers, the peers I admire right now who are writing fiction are really engaging with the changing times, with technology and isolation and alienation and with the technocracy that’s occurring over our lives. I’m somebody who is very pro-technology and very anti-technocracy. It’s a very different thing to say that I value the fact that my computer can do this and my phone can do that. And yet I refuse to be a tool of these companies and that’s what’s happening.

Do you feel like we’re in this moment where Asian and Asian-American writers are not only getting the attention they have long been denied to them because of certain identities, but also leading a charge for what fiction can be and how that intersects with activism?

Right now we’re only getting a taste of what’s to come or what can come. I think the political power of Asians and Asian Americans is growing, and I think it’s going to grow more only if we really recognize just how diverse we are because, as I previously stated, it is an enormously large tent.

One of the things that I routinely have to do, which does not make me any friends, is that I raise my hand and say, “Let’s not make generalizations about Asian-American fathers or Asian-American mothers.” And very often, the person I am saying that to is not a non-Asian or non-Asian-American person. I will routinely say, “I know you are a Korean woman, but before you talk about Korean dads, I want you to really think that through. How many Korean dads do you know?” And usually it’s one. And I’ll say to them, “Ok so maybe we’re talking about just your dad and your dad may be fantastic or your dad may be a total jerk or your dad may be just your dad. But let’s be more specific.”

The integration of more and more specific voices gives us a greater sense of humanity and gives a greater power to our community.

This drive for specificity feels really important within your own work. With the way you use your voice as a public figure now, how do you feel like you use social media and Twitter especially to call attention to the need for specificity?

I think social media is a very, very, very powerful tool. I think we’re only just understanding a fractional idea of the power it has — for good and for evil.

Whether I like it or not, whatever I say, people will go, “Oh all Korean people think this!” and I can jump up and down and say, “No! Min Jin Lee thinks this!” And they will still say, “No this must be what all Korean people think!” As someone who has studied quite a bit of history and the way that propaganda can work, I am that much more respectful of that which I can say and that which I cannot say.

Given the way that your work focuses on the lives of women in very specific moments in history, what are you thinking about as you see the events of today regarding Roe and reproductive rights?

I’m shocked and I’m angry. One thing I will say, though, is that I do not feel a sense of despair and I do not want to give in to cynicism. The one thing that history can keep teaching us about activism and positive change is that we must constantly work out of love, not hatred and not despair. We have to be very mindful of the fact that if Roe v. Wade is overturned, well-off women and girls and persons who can carry a pregnancy to term who have economic power will absolutely be able to access safe and legal abortion here or elsewhere.

As a practicing Christian who goes to church every Sunday, I do not believe that we should overturn Roe v. Wade at all. To me, doing so is not an act of love.

Me saying this is something that takes on some risk, but it is a risk I am willing to take because we are living in a nation that ties health insurance to certain kinds of employment. And we do not have universal child care, and child care is certainly not affordable to the average woman. Therefore, we are saying, “If you are poor and if you are without rights, if you are without access, if you’re living in a household in which you are afraid to seek abortion outside of your state because you may have controlling parents — if you are these things, then you are out of luck.” I do not think that this is in any way philosophically or religiously an act of love.

As a writer who is unabashed about calling attention to identities, what do you hope people take away from your novels?

I think one of the things that we’ve done in this country which is quite a shame is that Asians and Asian Americans are simply not known. One of the things I thought I would do in my social realistic novels is to call attention to the different kinds of people that I know and love and admire and dislike. I wanted you to know us. I want you to think, “Oh, they’re no different than the other people you’ve asked me to know through fiction.” I know a great deal about Russians and French people and Jewish people and Muslims and people from Africa and people from Latin America. Why? Because I’ve read novels and I’ve read memoirs that have come from those spaces. And I’m so glad to have done so. I would like for you to know the people that I know and love and respect. I think to do so is a good thing.