The people kept showing up at the small Northern California office where Natalie Adona and her co-workers help run elections. Three days in a row, they came to try to push a petition for recall elections, refusing to wear masks despite a mandate and physically pushing their way into the office, according to legal documents.

Adona and her colleagues asked for a restraining order against the three people, worried about the trio who they say kept showing up to harass them at their jobs. A judge granted it, then later extended it for one of the people, finding “clear and convincing evidence” that the same person “engaged in unlawful violence or made a credible threat of violence.” An attorney for the trio has denied wrongdoing.

The elections office briefly shut down walk-ins. Adona, who is an assistant clerk-recorder for the Nevada County Elections Office, said she has experienced several panic attacks. She still worries about her colleagues.

“It was a really unfortunate incident that led to me and my staff feeling pretty afraid,” Adona told The 19th. “Certainly, I think that having a restraining order is an extreme way to settle a problem that I would have liked to have sort of settled by other means. But the circumstances and our county counsel felt it appropriate to go in that direction.”

Across the country, election administrators such as Adona are facing increasing harassment and threats of violence ahead of the next midterm election — a lasting effect of the lies told by former President Donald Trump that the 2020 presidential election was rigged against him. (It was not, according to multiple courts and Trump’s own administration.)

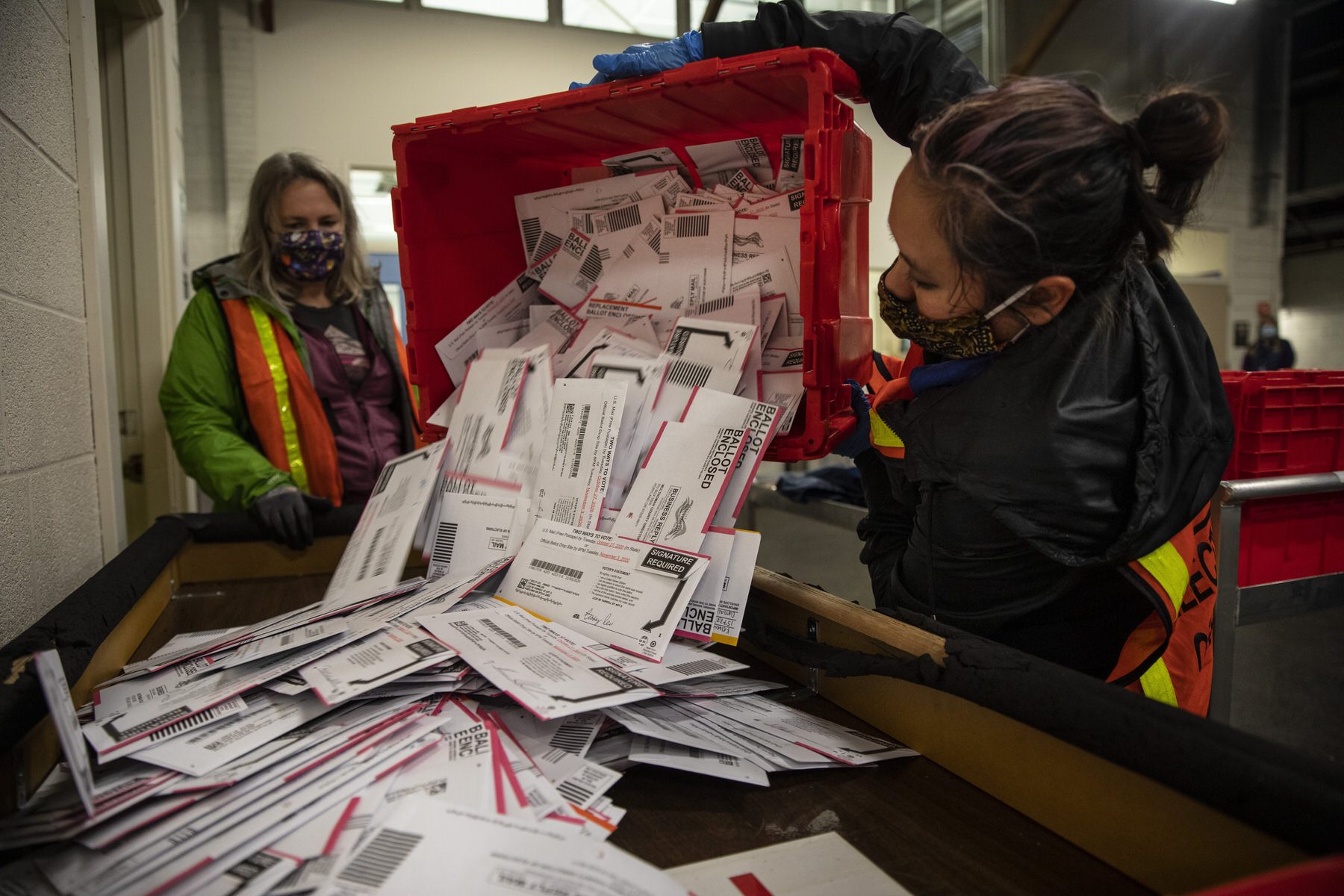

Most of those election workers — nearly 80 percent, according to survey data released last year from the nonpartisan Democracy Fund — are women. But while some states are passing laws that decrease the power of election officials, others are considering legislation designed to protect them against these increasing threats.

Oregon’s governor is expected to sign a bill into law in April that will expand protections for election administrators in the state. Under the bill, someone accused of threatening or harassing an election worker could face a misdemeanor charge that includes up to a year in jail or more than $6,200 in fees. The legislation would also allow election workers to hide their home addresses from some public records.

Ben Morris, a spokesperson for Oregon Secretary of State Shemia Fagan, noted the bill’s unanimous approval in the state Senate shows that election workers’ safety is not partisan.

“We’re sending a really clear message to people who may seek to interfere in elections that those actions won’t change the outcome of the election. Instead, they’ll be met with penalties,” he said.

Several states are considering related proposals. In Maine, a bill has been introduced that would add penalties for threatening an election worker. Legislation out of Minnesota would create civil and criminal penalties for interfering with an election official’s work, prohibiting intimidation, disseminating personal information about an election official and knowingly making false allegations about them. A Washington state bill would add prison time and a $10,000 fine if a person harasses an election worker.

In California, a bill would keep election workers’ home addresses private under a confidentiality program that helps survivors of domestic violence and employees who work at reproductive health care facilities.

A bill in New Mexico that would have also added some penalties for harassing election workers did not advance this session. But Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver said she is taking administrative action, in the form of more state and federal law enforcement partnerships aimed at improving physical security at the polls and ensuring election workers have more safety training.

“We’re living in a world now where threats of physical violence against election officials are more commonplace,” she told The 19th. “And so when we become aware of an issue we have to take the appropriate action where and when we can.”

Election worker protection bills come as Republican-led statehouses are passing bills that include new civil and criminal penalties for election workers. At least seven states enacted legislation last year that penalizes election officials. At least five states agreed to remove some election workers’ power to oversee elections in a nonpartisan manner.

Liz Avore is vice president of policy and law at the Voting Rights Lab, a nonpartisan group that tracks voting legislation. She warned that those Republican-backed bills, particularly those that remove power from longtime election workers, set the stage for institutional knowledge to be forced out of the profession.

“Legislation that interferes with the administration of our elections not only puts our democracy at risk — it targets a predominantly women-led workforce of election administrators, stripping them of their authority and creating a dangerous atmosphere of criminalization and intimidation,” Avore said.

Election administration is broadly defined work; several municipal government jobs — auditors, registrars — traditionally fall under the category. Adona’s job is a year-round position that in her case includes other tasks related to maintaining vital records. Ballot counters or poll workers are often temporary gigs that exist just around an election. Secretary of state offices vary, but often it’s an elected role that oversees elections for a state.

There is no centralized data collection about threats against election workers. But polling of nearly 600 election workers by the Brennan Center for Justice shows the increasing threats of violence for them. The data, released in early March, showed:

- 1 in 6 local election officials have reported experiencing threats because of their job.

- More than 3 in 4 local election officials say they feel that threats against them have increased in recent years.

- Nearly 1 in 3 local election officials say they know of at least one election worker who left their job at least in part because of fears for their safety, increased threats or intimidation.

- 3 in 5 local election officials say they are concerned that threats and harassment will make it harder to retain or recruit election workers.

Liz Howard, senior counsel for the Brennan Center for Justice’s Democracy Program, said organizers rely on anecdotal stories to measure the rise in harassment against election workers.

“We don’t know how many threats have been launched against election officials in Wisconsin or Arizona or Iowa,” she said. “But our survey, for instance, indicates that more than half of the election officials who do receive threats don’t report them.”

Some election workers and experts agree that state-level policy only goes so far without addressing the root cause of the threats, including Trump’s “Big Lie” about widespread fraudulent voting in the 2020 election. Some of Trump’s supporters are now running for local and statewide election seats, setting the stage for voting rights to be a key issue going into the next election.

Amber McReynolds is a leading voting expert who has promoted vote-by-mail and serves on the U.S. Postal Service’s Board of Governors. She also previously helped run elections in Colorado. She said that after the 2020 election, she hired private security to monitor her home after receiving online vitriol that included threats against her family.

“The core reason why people are getting harassed and getting death threats is because there were lies and conspiracies spread about the election process,” said McReynolds. “So I also think it’s important that we go to the core issue and hold those people accountable.”

She said the arena of voting rights advocacy is filled with women, many of whom have gotten threats, especially when they make public appearances.

“I know other women who have been harassed and targeted to the point where we get told, ‘Well, lay low or have a lower profile,’” she said. “Well, really?”

Chris Walker, an elections administrator in southern Oregon who has worked in county government for more than 20 years in the state, said she’d never faced the level of threats she has experienced since the 2020 election. After the presidential election, someone graffitied big white letters across the street from her office. The message: “Vote [sic] don’t work. Next time bullets.”

Walker, who is the Jackson County clerk, said the experience shook her.

“When you come to your office and see something like that — it was probably, I would say, eight- to 10-foot lettering on that parking lot directly across the street — that just drains you,” she said.

Walker said while the state’s new legislation is helpful, she also wants more funding for security infrastructure that can boost physical protections around election workers. She emphasized the importance of state-run elections that are distinct from federal oversight — her local county helps pay for its elections through a mix of revenue streams, including fees related to vital records. But she noted the increasing costs around printing, pamphlets, equipment and licensing. The office has tapped federal funds for some security upgrades.

“At what point does that all break without some sort of funding mechanism for the local jurisdictions?” she said.

According to the latest Brennan Center survey on election workers, nearly 80 percent think the federal government is either doing “nothing” to support them or is taking some steps but “not doing enough.”

The U.S. Department of Justice launched a law enforcement task force last summer to better address threats against election workers and others associated with the electoral process. This week, the Biden administration released a budget proposal that calls for spending $10 billion over the next decade on election infrastructure, including expanding vote-by-mail and making ballots postage-free.

Experts say Congress can further expand election worker protections and approve more funding for security infrastructure. They also believe more public education about elections is needed to demystify the process. Some want social media platforms to better respond to misinformation and disinformation about elections that can ricochet across the internet.

Walker said that safety concerns are never far from her mind but that she will not be deterred from doing her job.

“Elections are bigger than us as individuals,” she said. “You’re doing a job for democracy — for our democratic republic.”

Adona added that she too is committed to election work, a job she believes she was born to do. Adona is now running to replace her boss, who plans to not seek reelection and has endorsed her. But Adona said policymakers and society cannot rely on that kind of goodwill to last if there are no consequences for harassment and threats of violence.

“If we’re not going to punish certain types of behavior, then we need to be prepared for a slew of retirements,” she said.