For the first time in two decades, the United States was not at war on September 11 — the anniversary of the day that launched the country into its longest war.

The attacks changed the trajectory of a generation of people, and hundreds of thousands of women were among those who fought, first in Afghanistan and then Iraq. The 20th anniversary of 9/11, coming on the heels of the end of formal combat in Afghanistan, led many to stop and reflect.

Their memories are vivid. Katherine Rowe was sitting in her seventh grade science class when the Twin Towers fell in 2001. Her father was in the military, and she grew up on a military base and attended a nearby school. She remembers it took her two and a half hours to get back to the base that day due to increased security measures.

“My classmates who weren’t in a military family just drove home early that day,” Rowe said. “But for me, how I left home and how I returned completely changed — almost like living in an airport.”

The years after the attacks had a profound impact on her whole family.

“It’s like our whole world shifted,” said Rowe, who later joined the Army and served in Afghanistan. “We went from a military built off training cycles and preparation to do it again the next year to one that was focused on training and preparation to deploy to war.”

Rowe is one of several women veterans who shared their reflections on 9/11 with The 19th and discussed how the attacks ultimately led them to serve in the armed forces.

Another veteran, Julie, asked not to have her last name published because she is still on active duty. She was a high school senior, sitting in a humanities class, when the first tower was hit. Classes continued, and she was in calculus when the second tower collapsed. Before that moment, Julie was college-bound with a plan to study theater — a coach at the Juilliard School of Music in New York had even shown interest in her.

“I completely pivoted my life in response to 9/11,” said Julie, who is now 37. “Something I’ve learned about myself is I need to act when bad things happen. So I saw this all unfolding and felt this overwhelming sense of need to do something.”

Because her grandfather had served in the Air Force, Julie decided to follow in his footsteps. She joined the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), a college program that prepares young adults, and then went on active duty after graduating.

During more than 15 years in service, she traveled all over the world — from Central America to the Middle East — to assist with strategy, planning and command and control operations. For most of her life, she watched friends and loved ones sacrifice their lives for their country. Then, as the war ended, she worked fruitlessly to evacuate the families of Afghan interpreters that had served alongside American troops.

While the rest of the country marked this year’s 9/11 anniversary, Julie spent the weekend secluded in nature to be alone with her thoughts.

“As we approach the 20-year point, I’m wondering what my life would look like if I hadn’t joined,” Julie said. “I wonder if my spirit of service was wasted. I wonder if the lives of people I know who killed themselves after serving were wasted.”

Bernadette Fruge, 51, echoed Julie’s thoughts. Fruge served in the Army and Military Police force from 1998 to 2003, and then in Iraq for five months. Fruge said she thought about how the outcome could’ve been different, especially at home.

“We had the opportunity to come together as a country to face evil, and instead we have turned on one another,” she wrote to The 19th.

Na’ilah Amaru, a 39-year-old Army veteran, said that September 11 is always a difficult day, but that this year felt particularly heavy. Amaru, a Black and Indigenous woman, said she’s been reflecting on her love for her country but also the ways in which it falls short.

“Patriotism has become a political tool, weaponizing Black and Brown bodies,” Amaru said, adding that women veterans are often erased from war narratives altogether. “That can cause so much harm for Americans who look like me, and that irony has not lost itself on me.”

Amaru enlisted when she was 18 and served for four years, including one combat tour in Iraq where she was often separated from other soldiers because of her gender.

“I was 21 when I was in Iraq, fighting for democracy, liberation and trying to bring all the ideals of America into a new country,” Amaru said. Still, after all this time, she said, “we have not fully realized those ideals here at home.”

I wonder if my spirit of service was wasted.

Julie, an active-duty member of the Air Force who was spurred to join the military after the 9/11 attacks

Was the forever war worth it? Amaru said the answer was complicated.

“American soldiers lost their lives,” she said. “And I never want to say their sacrifice wasn’t worth it. But as someone who has been on the ground and watched from afar for the last 17 years, we have to be honest about how we’ve failed, what we could and should have done better for our soldiers returning home, for the soldiers who didn’t make it back and our allies who stood beside us for 20 years.”

Rowe, too, has taken a lot of time to reflect.

“I have had lots of emotions recently, but the one that sticks out is knowing how important my veteran community is to me,” Rowe said. “We have a generation of veterans that deployed multiple times, where 23- and 24-year-olds were asked to directly engage with the Afghan people and make decisions that could have had serious consequences.”

Rowe, who is now 32, said she had never planned on joining the Army. But then, as a teenager, she attended the funeral of Capt. Kimberly Hampton — the first woman pilot to be killed in Iraq — in South Carolina in 2004. The pilot’s “selfless service” stuck with her.

Rowe chose to sign up for Army ROTC and joined the military in 2008.

“I looked at it as an opportunity to serve my country — something that has been in my family since the Revolutionary War,” she said.

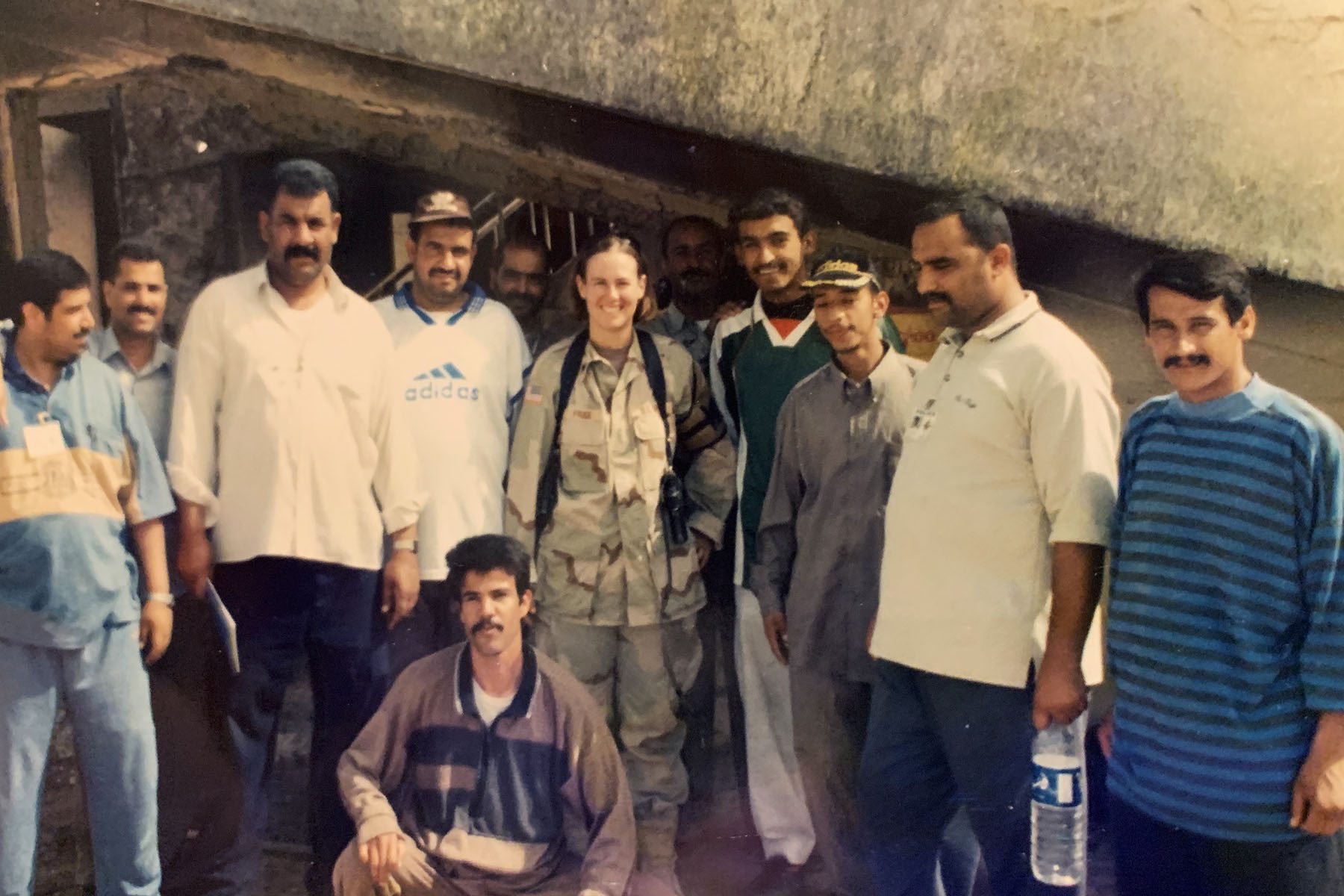

By 23, she was in Afghanistan — six months out of college and leading telecommunications management for 30,000 users. The pressure of that deployment in 2012 shaped the rest of her time in the military, she said, and still affects her today. Rowe said her seven years on active duty took her to Afghanistan and South Korea — half a world away from her dad, sister and other family members.

Rowe left the Army after seven years with the rank of captain. Now, as an MBA graduate and civilian, she is focused on helping veterans apply their skills to the civilian world and transition successfully to places that make sense for them.

“There are too many stereotypes about who we are as people,” Rowe said. “And often as a woman veteran, I am invisible until I talk about my time in the military. It’s important that our society shifts perspective on what veterans are capable of. We are the most diverse population of people within this country.”

While she’s sad to see what’s happened in Afghanistan, Rowe said U.S. efforts were not in vain. She knows that U.S. troops helped people by building schools, infrastructure and helping ensure Internet access was available.

Julie also looks back on her work in Afghanistan and sees seeds of hope.

“I am clinging to the idea that we created enough breathing room for women to create a new generation of activists and leaders who will be able to serve their country better than the U.S. ever could,” she said.