Nursing parents have been known to refer to their breast milk as “liquid gold” — precious drops that can sustain a baby’s life and prevent infection. In a global pandemic, that phrase might ring even more true for those who are passing their own antibodies from the COVID-19 vaccine to children who aren’t old enough to get the shot.

With research showing that vaccine antibodies travel through breast milk, the already complicated world of nursing a baby has, like everything over the past 16 months, become more complex.

The first stories I saw on the topic quipped about black markets for obtaining vaccinated breast milk or examined whether moms who’d had the shot should sneak pumped milk into older kids’ cereal. As I embark on my own journey as a vaccinated, nursing mom and dig into the science, I’m finding that it’s not so clear cut.

This is more than an academic exercise. My daughter, nearly 10 months, is starting to wean on her own. I’ve got a freezer full of milk for when I go back to in-person work as a professor at USC Annenberg, but the majority of it I pumped long before I got my Pfizer jab. My questions swirled:

Is there a difference between pumped milk, frozen milk, and milk straight from the source?

If I mix the pre-vaccinated milk with milk I pumped after March 3, is it less effective?

If so, what ratio should I aim for?

Or worse, should I ditch the pre-March milk altogether?

What if she only gets one bottle a day?

In other words, how much milk is enough milk to protect Matilda?

When Google led me nowhere, I started to ask the experts.

The bottom line from studies and experts who closely research lactation and infection is that antibodies are in breast milk. What happens next remains a bit of a mystery: Scientists don’t know if the antibodies translate to immunity from COVID-19, or if they even make it to a baby’s bloodstream. Still, they are quick to say the milk offers some form of protection.

“I cannot tell you the magic amount of milk that is going to do this, but I can tell you that reasonably … the more milk the better, the more milk, the more exposure to antibodies,” said Rebecca Powell, a human milk immunologist who leads a research program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“That doesn’t mean if you’re supplementing that it’s not going to have a protective effect,” she said. “Some milk exposure is going to be better than no milk exposure.”

When the pandemic began she knew that research on all aspects of COVID-19, immunity and breast milk would be necessary. Powell, a mother of three, is a microbiologist and immunologist by training who breastfed her own kids. That led her to her work, which focused on flu and HIV pre-pandemic. Research shows, for example, nursing parents with flu immunity have measurable antibodies in their milk, she said, and those babies are much less likely to contract the flu during the first six months.

While everyone I spoke with was steadfast that breastfeeding is more likely to protect children from (any) infection and encouraged all lactating people to do so, they said transferring antibodies is not the same as if the child received a vaccination directly.

The simplest explanation I got, and without including all the acronyms here, is that the molecules of what’s known as secretory IGA (SIgA) protecting the body from toxins are large, and a child’s digestive system probably is unable to break them down enough to prompt any benefit. It’s a similar argument author Emily Oster laid out in “Expecting Better” about certain prescription drugs. Some are considered safe for pregnant people because the size of the molecules means they can’t pass to the fetus. (Oster did not respond to my request for an interview.)

The antibody response for vaccinated nursing parents is “robust, and stronger than what you get with natural infection,” according to Christina Chambers, a perinatal epidemiologist, UC San Diego professor and director of the Mommy’s Milk Human Milk Research Biorepository. That antibody response also lasts more than a month or two, she said, based on her program’s study of milk from about 1,200 vaccinated women who provided their samples.

The research did not find anyone with a serious adverse reaction to the vaccine, though lactating mothers did report a short-term reduction in their milk supply that returned to normal after about 72 hours post-shot, Chambers said. That’s a common response to vaccines, and doctors recommend the vaccine for all who can get it.

The study also asked the moms to document any adverse effects in their infants, and very low numbers of people reported problems from any of the vaccines, she said. The findings all point to antibodies getting to the baby. What the research does not show, however, is how much protection breastfeeding provides because it’s not clear what is getting into the bloodstream, she said. There are theories that the milk simply being in the child’s mouth can protect them, but no research to measure or confirm it for certain.

How much milk is enough? “Not a clue,” Chambers said.

She said she has been asked by lactating moms if they should give breast milk to their 5-year-old or a high-risk grandparent. “Not a clue what the answer is,” she repeated, and, “It will be hard to answer the question.”

I tell Chambers about my weaning dilemma. She told me that the health care workers who run the newborn nursery at her hospital said this is the last time you want to be weaning a child.

If someone is vaccinated, “we think there is good reason to continue to breastfeed to provide some protection for the baby, but that has not been proven yet, and we don’t have enough information to say that the vaccination would provide more protection if the mother is breastfeeding exclusively instead of feeding fewer times in a day,” Chambers said.

Are the antibodies still there if the milk has been frozen? There would be a slight decline in antibodies from a single thawing of frozen milk, Powell told me, but not enough to concern her.

I told both Chambers and Powell about something our doula told me when I was pregnant with my son in 2016: Every time you pick up the baby to nurse, you should take a big up-close inhale. That will prompt your body to make the right antibodies for the baby in that moment. In other words, if the kid’s body is about to show the signs of a cold, your own milk can help fight off that specific cold.

While Powell said it “sounds a bit fanciful as a scientist,” she added that actually, the baby’s saliva sends a signal to the breast to “change the milk.”

Chambers also suggested there’s something to it. The hypothesis, she explained, is that saliva produced from a baby nursing can prompt the parent to start to produce antibodies in response to an oncoming infection.

But the hypothesis, like so many related to breast milk, still needs to be tested. That’s one reason everyone I spoke with decried the lack of substantial research on the topic.

“We know so little about this thing that 99 percent of the population is supposed to be fed entirely for the first six months of their life,” Chambers said. Her own research relies on lactating people willing to donate milk for study. Over the course of the pandemic 7,000 people have contacted the center to contribute pumped breast milk to science, she said. “We have been overwhelmed.”

As I sat down to write this, I had one month until my return to campus. That means that the curse (and blessing) of working from home with my family day in and day out will come to an end. I opened the freezer and started trying to do the math.

Matilda nurses four times per day, give or take a cranky afternoon. Sometimes I weigh her in between to figure out how much milk she’s getting, and it’s usually between 2.5 and 5 ounces per session.

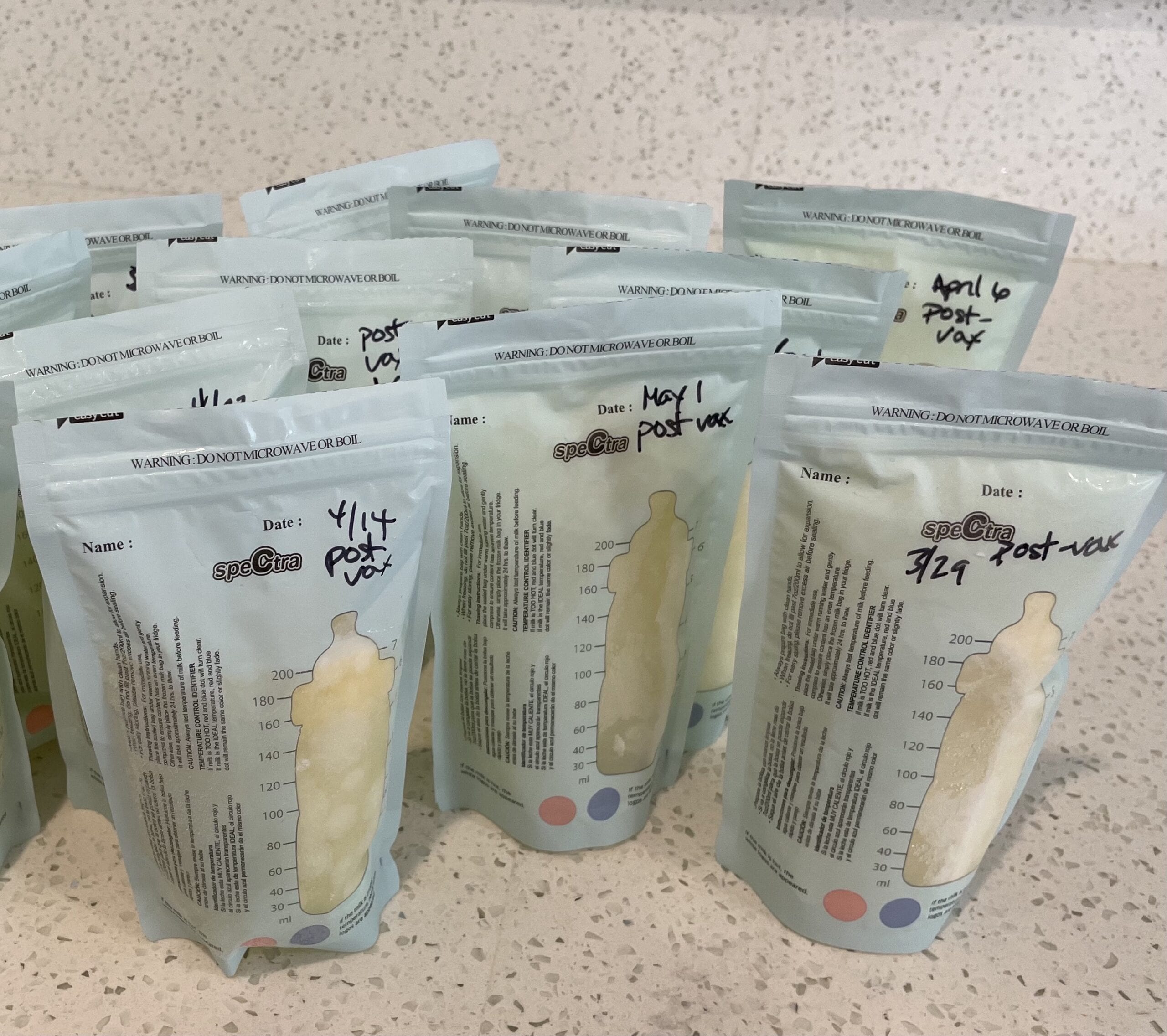

As I inventory the sealed bags of pumped milk, all labeled with the week they were pumped, or the critical words “post-vax,” my heart starts to feel heavy. If I pump during the work day, I can probably get Matilda to her first birthday. But can I stretch it until babies are eligible for the vaccine? Is it even worth it?

One of the Facebook mom groups I’m in has had several threads pondering how long to continue nursing in this pandemic era.

“I’m still breastfeeding at 20 months and that damn vaccine is the main reason I am still powering through,” wrote Deana Speck. Now, she’s at 23 months, and still going, Speck told me via Messenger.

Alice Fountain, 37, of South Pasadena in Southern California, extended breastfeeding longer for her toddler son after she was vaccinated “on the minor small chance that he might be able to get a little bit of antibodies,” she told me in an interview. Fountain had responded to the other mom that she was in a similar situation with her son, who turns 3 in October. When we spoke, she urged everyone to get vaccinated and trust in science.

“I don’t care what it was — 1 percent, 50 percent less likely to get severe symptoms — if there might be some health benefits or a fight against COVID then I would continue to do it,” Fountain said.

“This is one of the number one questions we’re getting,” said Andrea Ippolito, the founder of Simplifed, a breastfeeding support company and network of lactation consultants who help new parents via telehealth. “Moms one or two years into their journey wonder if they should keep it up.”

A breastfeeding mom herself, Ippolito, 37, said she is mostly pumping because she has suffered from mastitis, a painful infection usually caused by a blocked milk duct. She wants to make sure her 2-month-old continues to get protection, but might have stopped in different circumstances.

Lactation consultants recommend “if you can and if you’re able to … continue to breastfeed the research suggests it is potentially protective against COVID-19,” she said.

Still, she said it’s a conundrum for moms because babies “need to be continually receiving that milk that has the antibodies. It would need to be constant,” said Ippolito, also a faculty member in the engineering department at Cornell University.

I ask her my million-dollar question: How much is enough?

“What the research shows is that we don’t know the answer to that question,” she said. “A mostly breastfed baby is still getting antibodies, we don’t know what levels.”

As I interviewed these experts, I kept waiting for someone to tell me what to do. My best friend, a family medicine doctor at Kaiser, didn’t hesitate: “It’s time to stop.” My mom, who notices Matilda’s little tooth breaking through on the bottom gum, says the same. “Get ready to wean,” she tells me.

With my son, I had no choice but to stop breastfeeding. I went back to work at the Los Angeles Times in the first year of the Trump administration. I barely saw Maxwell, missing all the milestones and frantically pumping between meetings in my office with a sign on the door telling people I wasn’t available. It didn’t take long for my frozen supply to run out and my body to call it quits.

As I prepare for this big decision, I realize it’s not so different from my family’s choice to stay home, wear masks and lay low for the past 16 months. If there’s even a slim chance I can protect our little girl from illness, shouldn’t I do it?

My reasons I would stop feel so selfish. Sometimes it keeps me up at night. If I wean her, my body can feel like mine again. I might even be able to lose the rest of the baby weight. Pumping is the worst. I’ll get more sleep, since either parent can get up at 5:45 a.m. on a Saturday with a bottle.

Powell, of Mt. Sinai, helped me feel a little better about it.

“There are many other ways you can protect your child from COVID before they can get vaccinated themselves,” she said. “Don’t drive yourself crazy for this relatively small effect.”