This article was updated on May 25 after Darnella Frazier issued a statement on the anniversary of George Floyd’s death.

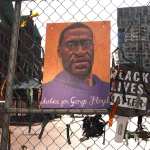

In May 2020, the world’s attention turned to Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed by a police officer. After Floyd’s death came a summer of protests and, nearly a year later, three convictions for Derek Chauvin, the former police officer who murdered Floyd.

Somewhere amid all of this chaos was Darnella Frazier, who was 17 when she captured Floyd’s final pleas for help on camera — footage that would serve as primary evidence in the trial against Chauvin.

Frazier testified at the trial, sworn in just days after her 18th birthday along with three other girls. She told the jury in emotional testimony that she stays up at night “apologizing and apologizing to George Floyd for not doing more.”

On Tuesday, Frazier said the following in a public statement:

“I didn’t know this man from a can of paint, but I knew his life mattered. I knew that he was in pain. I knew that he was another Black man in danger with no power.”

This sense of responsibility is common for Black girls, experts said.

BraVada Garrett-Akinsanya, a licensed clinical psychologist and expert in racial trauma, said in many ways, Frazier’s thoughts are not a surprise.

“I think that expression sits in our community very widely,” Garrett-Akinsanya said. “And the girls who experience these traumatic experiences, they really don’t have a lot of places where they feel safe in the community or outside.”

For young Black people, and young Black women and girls in particular, the mental health impacts of being a bystander to police violence are far-reaching. Mental health professionals have noticed an increase in the severity of mental health conditions among Black women and girls who witness police violence, even through video. To tackle it, experts are calling for increased trained mental health professionals in the field of racial trauma and specific spaces for Black girls to heal.

In the long term, the effects of witnessing police violence can rewire the brain.

Frazier also spoke to these psychological changes in her statement.

“I couldn’t sleep properly for weeks,” she wrote. “I used to shake so bad at night my mom had to rock me to sleep.”

She continued: “Having panic and anxiety attacks every time I seen a police car, not knowing who to trust because a lot of people are evil with bad intentions. I hold that weight.”

Garrett-Akinsanya says media exposure to the murder of Black people at the hands of the police can cause the body to live in a sort of fight or flight state; it cannot actually rest if the individual is constantly being re-traumatized. This sense of fear can be heightened for Black girls, who doubly feel the strain being a girl and being Black, Garrett-Akinsanya said. Studies show that Black women and girls experience higher rates of rape and sexual assault, for example.

“The impact of trauma on brain development, on the way we engage in thoughts, feelings and behaviors is very hurtful,” she said. “The reason we can’t heal is because the trauma keeps coming.”

And that trauma is generational, Garrett-Akinsanya said. As a consequence, Black girls must deal with their own trauma while also navigating the impacts on their mothers, aunts or grandmothers.

Such a dynamic can lend itself to one having a “negative sense of value.”

“When it comes to our Black bodies as women, we internalize that lack of value and [that] impacts our behavior,” she said.

Maryam Jernigan — an expert in the area of Black youth mental health — says the side effects of witnessing police brutality can manifest as anything from physical numbness to depression and anxiety.

“The more you’re witnessing, the more that you’re hearing about, the more that you’re watching videos of violence against individuals that you self identify with, it can decrease one’s own sense of safety and, quite frankly, impact one’s own sense of mental health,” Jernigan said.

Black mental health experts call on a system in which Black girls are listened to and given the chance to express their complex emotions.

“Without replenishment and healing and recovery, there is just more of a propensity for harm to happen long term,” said Akua K. Boateng, a licensed psychologist and expert in racial trauma. “So we counteract that by creating spaces for people to heal, for girls to have what has been taken away by inequitable systems.”

Boateng said she noticed a correlation between the increase in widespread content involving incidents of racial trauma — like the Chauvin trial — and the physical reactions of pain for her clients. Even she felt an increase in chest pain, body aches, insomnia and disordered eating after hearing stories of police violence against Black people.

Creating healing spaces for Black girls will take work, though, said Jernigan, who has trained thousands of mental health professionals in the field of racial trauma.

“Research actually demonstrates that when we are silent about the realities of how race and racism shows up in the lives of Black girls, it’s actually to their detriment,” Jernigan said. “How are you really cultivating and curating an environment of inclusion, that really is intentional about understanding systemic racism, as well as interpersonal racism.”

But it starts with humanizing Black girls and their experiences, Garrett-Akinsanya said, understanding their “mind, body and spirits.”

“The girls we raise and love, they need to dance to their own sounds and their own beats, their own power, their own patterns,” Garrett-Akinsanya said. “And they will be successful.”