Maria Fernandez in Houston was picking up her teenage son when she saw him sitting alone in a hoodie — his favorite clothing — listening to music. The boy, who will be 18 in June, wasn’t paying attention to his surroundings.

“My heart stopped,” the 55-year-old said. “And I just thought, ‘Oh my God, how many times have we had this conversation?”

Fernandez’s two sons are Afro-Latino. Around the country, mothers have watched repeatedly as police violence unfolds against people who look like their Black and Brown children.

The trial of Derek Chauvin — the former Minneapolis police officer who was convicted in the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 — added another layer of emotion to a country already beleaguered by racial unrest. On Tuesday, moments before a woman-majority jury found Chauvin guilty on three counts, a Black teenage girl was fatally shot by a police officer in Columbus, Ohio. Police released video footage that showed three girls in a brawl — one wielding a knife — and an officer firing his weapon multiple times after yelling, “Get down! Get down!” The teenager, identified by county officials as Ma’Khia Bryant, was taken to a nearby hospital, and died of her injuries.

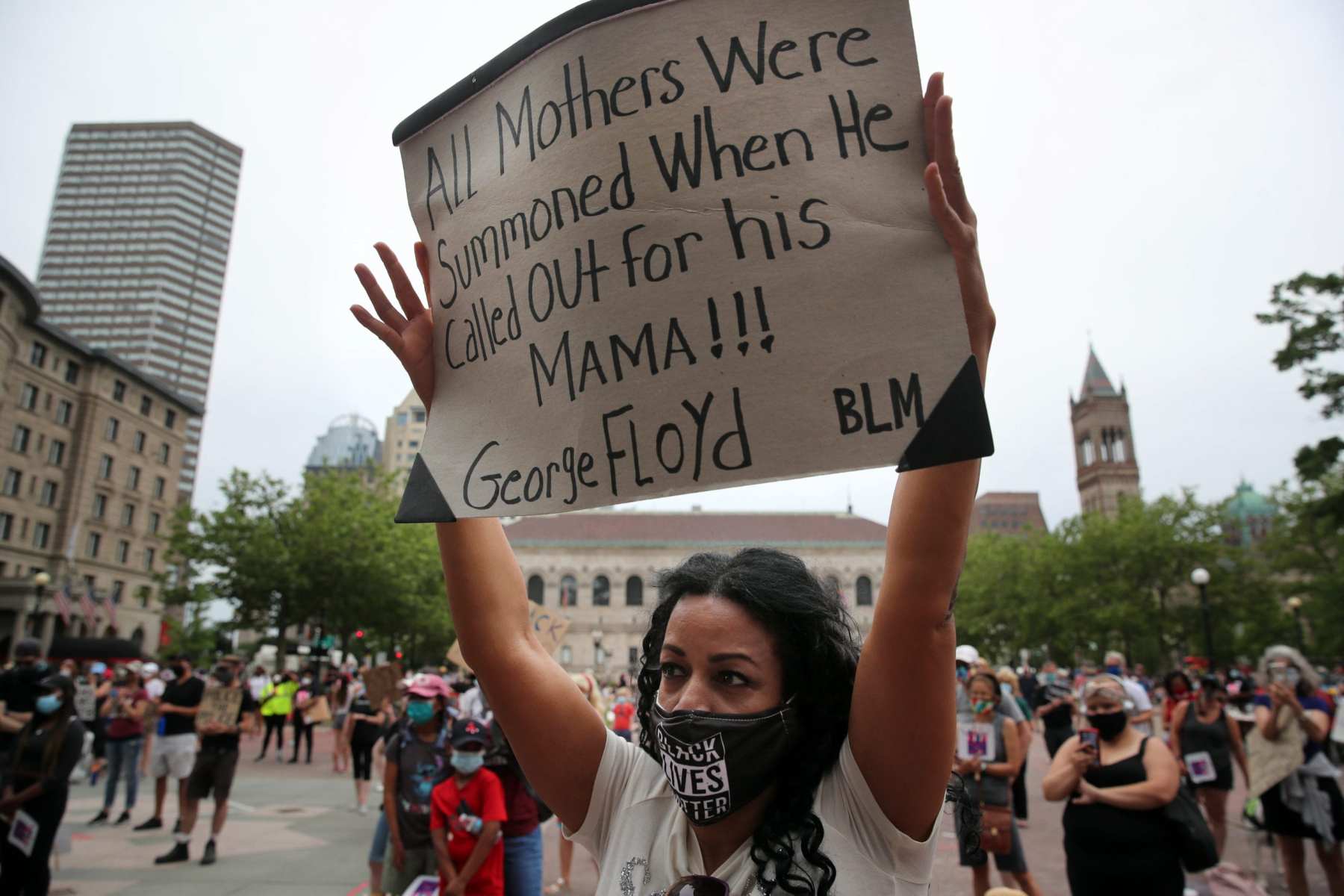

Fernandez said she sometimes thinks of the fact that the 46-year-old Floyd called out for his mother before he was killed.

“As a mother, it’s heart wrenching,” she said. “It’s really difficult to think that people in power can do this.”

Floyd’s death sparked a wave of protests and marches against racial injustice in America and put a renewed focus on the country’s long and fraught legacy of racism and violence against Black people.

In some ways, the outrage and feelings of helplessness aren’t new to mothers of people of color, who are more likely to be killed by police officers than White people are. In 2021 alone, at least 93 people of color — including 13-year-old Adam Toledo in Chicago and 20-year-old Daunte Wright, who was killed mid-April less than 15 miles from where Floyd died — have been fatally shot by a police officer, according to the Washington Post. (An additional 70 people’s race was listed as “unknown.”) Bombarded with this backdrop of police brutality, some experts argue that, for mothers of Black children, the violence is a reproductive issue.

Jennifer Driver is the senior director for reproductive rights for the State Innovation Exchange (SiX), an organization that works with state lawmakers to pass what they describe as progressive public policy. She said reproductive health is the idea of having the right to decide when and how to become a parent and how to parent your child safely. She said women with children of color view motherhood through a unique lens.

“That threat of police violence or police brutality in communities is something that many communities of color have to consider before even just deciding on whether or not they’re going to become a parent,” Driver said. “In a way that I’m not sure that their White counterparts even have to think about.”

Rachel Hardeman, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota, co-authored a 2017 article in the American Journal of Public Health that investigated the links between police brutality and poor health outcomes among Black people. Black women in the United States — when compared with their White counterparts — are twice as likely to experience a preterm birth, a low birth weight infant or the death of a child before age 1.

“My earlier research assessing racialized police violence as a form of stress for Black women of reproductive age demonstrates that the unpredictable but persistent possibility of racialized police violence in one’s community is a debilitating burden disproportionately borne by Black women and their families,” Hardeman said in a statement.

This month, Hardeman launched a five-year study funded by a $1.8 million grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development — the first of its kind — to investigate the association between racialized police violence and the health of Black infants.

For generations, mothers have given their children of color “the talk” on how to behave around police officers, especially during traffic stops.

“There’s a point at which young Black men are told that basically their childhood is truncated,” said Felice Gray-Kemp, a 52-year-old mother in Connecticut who has an 11-year-old Black son. “Because you go from this innocuous little bubbling lump of love to a future convict in the eyes of society, in the eyes of policing.”

Fernandez, who is Latina, said she’s had the talk with both of her sons, and she keeps an open line of communication over the issue of police brutality whenever a high-profile death dominates the news.

“I just think it’s a shame that their childhoods have to deal with this, that they have to understand how to deal with it, have to feel less than, even though they are truly loved and in a good environment,” she said. “But they have to feel less than when they go outside.”

Dr. Jamila Perritt, an OB/GYN and president of Physicians for Reproductive Health, said she sees a direct correlation between the trauma of police violence and reproductive health.

“It’s something that has been ever present for me, as a parent, and certainly something that I remember being present [for], as I was parented as a child,” she said. “That concern and the realization, that there are forces outside of us, and our sort of safe space, that we can’t protect them from.”

Gray-Kemp is preparing to give her son the talk before he enters middle school next year. She said he is an “extraordinarily high-functioning autistic” boy, and she feels like she’ll need to take extra precautions. She has done role playing with her son so he knows what to do if he has an interaction with a law enforcement officer.

“He’s so high functioning, his challenges are not evident. And so him moving a little slower might be taken as him being uppity when actually he’s processing as he goes,” she said.

Gray-Kemp said there are times when the logic of her precautions have stressed her out. But she also wants to highlight the joy of being a parent, especially to a boy she described as her best friend.

“Having the luxury of time, resources, maturity and being an older parent makes being a mother — an act that I never thought I wanted — the most glorious and delicious thing,” she said. “And I refuse to have this moment, or any moment, detract from me and my husband and my son’s experience of that.”

Perritt said that as her own Black son ages, she feels a “significant sense of urgency” for the world to be better than it is. She also believes in highlighting the resiliency of mothers and children of color instead of just focusing on their pain.

“Knowing that I’m turning him out into a world that is unsafe for him, terrifies me,” she said. “And so thinking about, ‘How do I manage that?’ And also not have him grow up to be a fearful person. I want him to be big, and bold, and take chances. I want him to live a full life and not live shrouded in the fear and hate.”

Gray-Kemp hopes that the hyper awareness of this moment means that women and parents of White children are having more conversations about how to be good people and allies.

“There’s this opportunity for intersectionality that I think is unique to this moment. Because you see White and other non-Black allies marching, saying, ‘I see you,’” she said. “… We want for our children the same freedoms, and consequences when they mess up, as everyone else. Why is that so hard to see? Why does a [White] kid who does a prank get to go home with a police escort, but we can’t play on a playground without being shot and killed by cops?”