Working with first-time voters stands out among Hildie Brooks’ favorite memories as a poll worker.

As people left her Arizona polling place with an “I voted” sticker, Brooks and her co-workers would throw mini celebrations, letting out a “woo!” or sometimes applauding.

“We didn’t pull out streamers or anything like that. But we would honor that person,” the 67-year-old said. “To me, that’s what it’s about. It’s the unity of everybody participating in the democratic process of voting.”

Brooks has been a poll worker for more than a decade. But the retired middle school teacher is worried about the potential health effects that COVID-19 has on people her age — she has barely left her home since March. Because of the pandemic, she won’t be a poll worker this year.

“It’s very disappointing,” she said. “I look forward to it so much. Just the thrill and the honor of working at a polling location.”

Across the country, women like Brooks — who experts estimate have made up the bulk of poll workers — are taking a step back from the seasonal work that has long been critical to running America’s decentralized election system. Some election groups have warned of a growing shortage of poll workers, with long lines during the primaries in states like Georgia and Wisconsin putting a spotlight on their absence.

Age data reported for 53 percent of poll workers in 2016 showed that 32 percent were between the ages of 61 and 70 and 24 percent were 71 and older. There is no comprehensive data on the gender of poll workers, but researchers believe that women have led the charge.

“There isn’t much systematic research that definitively shows that poll workers have been largely female, but I think the reason for that is because it sort of goes without saying,” said Mitchell Brown, a political science professor at Auburn University who has extensively researched election administration.

Sarah Courtney, a spokesperson for the League of Women Voters, agreed that the underreporting of who is serving as poll workers highlights a reality about women in elections: “We’re just really taken for granted.”

Since Brooks is sitting this year out, she asked her 38-year-old daughter Erica to sign up. There’s a familial connection to the job for Brooks: When she was a young girl growing up in California, her mother was a poll worker. She hopes Erica will carry on the tradition. After an initial conversation with her daughter, Brooks mentioned it again on a call, and followed up with a text message in the family group chat.

Erica, a graphic designer, was impressed by her mother’s tenacity.

“I’ve always really admired her dedication to working the polls. She’s always talked about it as something that she really enjoys doing,” Erica said. “And I’ve always thought, ‘Yeah, someday when I’ve retired and I have extra time on my hands, that would be a fun thing to do.’ So when she brought it up I thought, ‘Oh, I guess maybe now is the time.’”

Already, young women have begun to take up the mantle of becoming poll workers. Mallory Rogers showed up at her Georgia polling location at 6 a.m. for the start of a nearly 14-hour shift during the June primary. Almost immediately there were several challenges: A set of new voting machines were not working properly, and some voters showed up in person after not receiving an absentee ballot at home, creating questions about proper protocols. It all culminated in long lines.

“It was a really stressful day,” the 17-year-old said. “But it was also really, really empowering to help people vote.”

When Rogers shared her experience with her 71-year-old grandmother, she told her granddaughter that she herself had been a poll worker.

“It’s empowering to know my grandma has done this,” Rogers said. “I’m carrying on a legacy.”

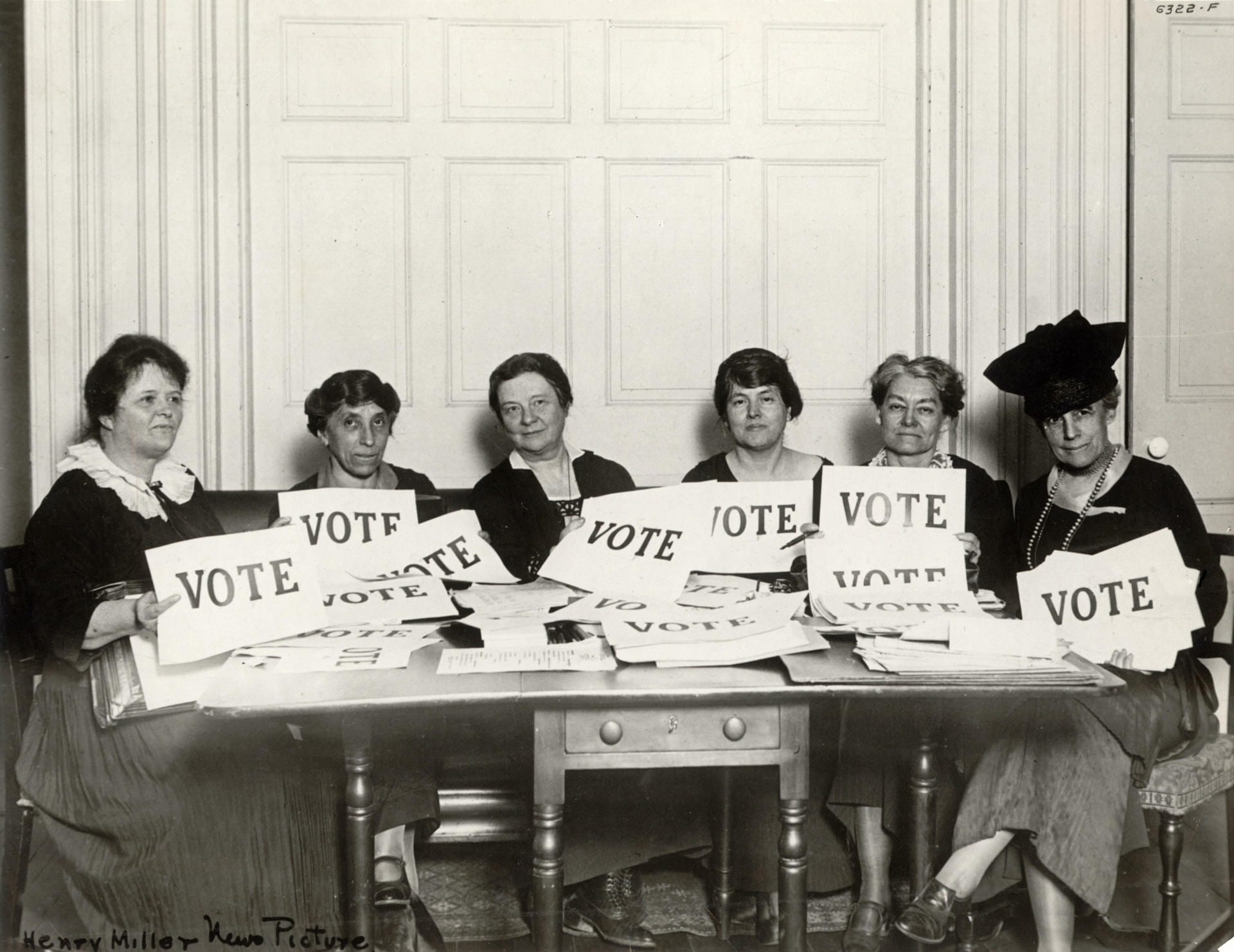

It’s difficult to know exactly when and how women became so linked to the elections system that Americans know today. There appears to be limited historic data readily available, but women have been at the forefront of civic engagement.

The 1920 ratification of the 19th Amendment, which effectively granted White women the right to vote, led women to run expansive education efforts to increase the number of women registering to vote. This included mock plays featuring women as election clerks. The League of Women Voters, the voting rights group founded six months before ratification, held “schools of citizenship” to train women in civic duties ahead of the fall elections. The lessons, according to a newspaper clipping, would specialize in “practical politics, the American system of government and the machinery of elections.”

Courtney said the organization’s educational outreach today includes organizing hundreds of candidate debates and forums around the country.

“Every area of this work, every level, women are powering elections,” she said.

Brown, the professor, noted that for decades, working the polls on Election Day may have been viewed as a clerical-style job that could fall to women.

“They’re given a small stipend for the time period that they do their work. And what that stipend is varies depending on where you are,” she said. “But it’s certainly not enough to live off of. And so it becomes essentially volunteer labor.”

As states added election policies, the need grew for officials to help administer them. Over time, it resulted in a codified election system with different rules depending on the state, with women predominantly running them.

Women often also lead the administrative side of elections year round. The typical local election official (LEO) is most likely a White woman between the ages of 50 and 64 years old making about $50,000 annually, according to a 2019 report from Democracy Fund, a nonpartisan voter advocacy group. LEOs are much more likely to be male as the election jurisdiction size increases, according to the report. In those instances, the men tend to be younger than 50 and earn higher salaries.

Tammy Patrick, a senior advisor at Democracy Fund said women’s power in election administration appears to still have limitations. Most secretaries of states, often the top statewide position for overseeing elections, are men.

“I think that that’s also another element to this, is that glass ceiling that pervades not only the size of a jurisdiction, which also equates with more pay, larger budgets, larger staff, all these other things,” she said. “But even from the jurisdictional local level to the state level, that can also be another barrier that women are still breaking through.”

Patrick, who used to train poll workers in Arizona, said it’s hard to quantify the scope of women’s roles in elections. But as the temporary poll worker system (with different rules and requirements by state) was created, women helped lead its implementation.

“It’s definitely the case that I have seen women playing a very prominent role across the country in both recruiting poll workers, training poll workers and then being poll workers,” she said.

More than 900,000 poll workers helped operate more than 116,000 polling places during the 2016 election, according to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. In 2018, a midterm year, more than 600,000 poll workers staffed more than 200,000 polling places, according to the commission. States reported deploying an average of eight poll workers per polling place on Election Day.

Poll workers will continue to play a critical role in this year’s general election. Although the pandemic has led to a record number of requests to vote by mail, experts still expect high turnout for in-person voting.

After reports of long lines during the primaries, Power the Polls launched this summer with a goal of recruiting 250,000 people to sign up as poll workers. It has partnered with more than 100 groups, including LeBron James’s More Than A Vote.

In just a few months, more than 670,000 people have signed up through the site to begin the process of becoming poll workers.

Among the dynamics leading to a spike in interest is that, in many instances, it’s a paying job during a time of record unemployment.

“That’s a good way for them to pay bills,” said Chris Hollins, the clerk of Harris County in Texas, the state’s most populous county. The county is paying $17 an hour, at minimum, to poll workers.

Hollins said election officials have received nearly 40,000 applications for more than 11,000 slots.

“We haven’t had any issues,” he said. “In fact, we’ve had a good problem, the opposite problem. There are so many people applying that we’re actually having to turn people away at this point.”

In 2016, more than two-thirds of poll workers were 61 years or older, according to limited data compiled by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. The pandemic has laid bare the lopsided reliance on older Americans to run elections.

Organizers for Power the Polls estimate more than 60 percent of people who have signed up to be a poll worker through the site are under the age of 50, and nearly 40 percent are under the age of 35.

Robert Brandon is president of Fair Elections Center, the nonprofit that helped launch Power the Polls and does advocacy work around mail-in voting. He said young people will create a new network of poll workers for decades.

“It is a whole new generation of poll workers, which to me is the thing that we ultimately want. Not that we don’t like the people that were working before, they’re great,” he said. “But we need more diversity. We need more tech-savvy people. We need more bilingual options. And the one positive of this pandemic-driven surge of interest in poll working is we’re going to see that.”

Ella Gantman is among a group of Princeton University students who helped develop the Poll Hero Project, an initiative aimed at signing up college and high school students to be poll workers. The group says it has recruited more than 30,000 people to sign up to be poll workers, including 19,000 who are 16 and 17 years old.

“It’s Gen Z reaching out to Gen Z in order to create a tangible change within our generation,” she said.

Gantman has seen the data that shows young people typically vote 20 to 30 percentage points lower than older voters. But as they increasingly become a larger slice of the eligible voting electorate, Gantman, who was born in 2001, thinks Generation Z will turn out to vote in powerful numbers. She noted that her generation grew up in the era of endless school shootings, leading to a new level of activism to address issues like gun violence. Young people are also credited with driving solutions around climate change.

“Young people really do have so much power, but that power hasn’t necessarily been reflected in numbers yet because we haven’t had literally the right to do so,” the 19-year-old said about voting in a presidential election. “I really hope that this year we can prove some people wrong.”

An expansive infrastructure for poll workers has long been missing, often leaving poll worker recruitment efforts up to officials in states and counties. A report about the 2018 election noted that “recruiting poll workers continues to be a challenge for many states and jurisdictions, with nearly 70 percent of responding jurisdictions reporting that it was “very difficult” or “somewhat difficult” to obtain a sufficient number of poll workers.”

In 2018, Fair Elections Center launched Work Elections to create a more centralized resource of information for poll workers. Its site, which at the time featured information for nine states, included details like age and training requirements to be a poll worker. In the run-up to the 2020 election, Fair Elections Center partnered with several groups to promote an expanded database of poll worker information for most states through Power The Polls.

“The systems are not set up to make this easy,” said Erika Soto Lamb, vice president of social impact strategy for MTV and Comedy Central, among the companies working together this year to promote poll worker recruitment through Power the Polls. “The collaboration that’s happening now between civic engagement organizations and brands and influencers has been really powerful. That partnership is what is allowing us to attract attention and to do it in a way that then connects to the local election administrators.”

Sarah Skaleski became a poll worker through Power the Polls for the first time during the August primary in Michigan, where the 18-year-old lives. During a roughly 16-hour shift during the primary, Skaleski helped voters make sure they were at the right polling place, helped people receive their ballots and ensured COVID-related safety guidelines were being followed. That election was also her first time voting. The high school senior used her lunch break to bike over to her assigned polling location to cast a ballot.

“It was really interesting just to see how much went into every little detail of the election and how much was put in place to make sure that everyone could vote,” she said.

She plans to be a poll worker on Election Day. She feels so strongly about being a poll worker that she has recruited her parents and 16-year-old sister to work on Election Day, too. They haven’t sorted out how they’ll get to their early morning assignments if they’re stationed in different locations. Skaleski might bike again to work.

“It’ll be like the first election that we’re not all together,” she said. “But it’ll be worth it.”

The culmination of organic, word-of-mouth encouragement from people like Skaleski and multiple voting organizations and businesses working together to promote a national recruitment effort has led to a massive interest in being a poll worker this year.

But more poll workers are needed. Earlier this month, groups that track poll worker recruitment efforts through public data announced that 485 counties across eight battleground states (Arizona, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin) are still at high risk for poll worker shortages.

“There’s a huge need,” said Quentin Palfrey, chair of the Voter Protection Corps, a group that helped release the data along with Carnegie Mellon University. “The point of this tool is to give the best available, data-informed information about the places that we see as being at high risk for not having enough poll workers and to help local officials and local groups and others direct the resources of the places where there’s the greatest need for help.”

Palfrey estimates that one million poll workers would be the most effective way for the general election this year to run as smoothly as possible. It’s unclear when comprehensive data on the number of poll workers in 2020 will be available.

Still, though the number of people interested in being poll workers has made organizers hopeful, it has also led to confusion. Some people have shared on social media that they’ve yet to hear from election officials about their inquiry to be a poll worker.

Soto Lamb with MTV and Comedy Central noted that organizers have started to ask people to stay patient, in part because some election officials wait until closer to Election Day to reach out.

“Election officials are further behind schedule because it’s overwhelming, and things have gotten more complicated in the pandemic … we sounded the alarm bell, we’ve captured a lot of people and we are sticking with them throughout the process,” Soto Lamb said. “But yes at the end of the day, the connection is made with the local election administrators and it is no doubt a complicated job that they are overseeing right now.”

One of those caught in limbo include Erica Brooks. After making her inquiry about being a poll worker in Arizona, Erica said she received a lengthy email about the process and rules in her respective county. Then silence. She checked in several more times before an election official told her directly that the county had received thousands of inquiries for poll worker shifts. She’s on a waiting list in case a slot becomes available. The election official asked her if she’d be willing to do clean-up work on election night instead. Brooks said she’s happy to fold chairs or sweep floors. She just wants to help.