Rev. Al Sharpton’s words rode the heat waves over Washington, D.C., hitting Brigette Brantley with the force of six months of pain, a lifetime of inequality.

Sharpton addressed tens of thousands of protesters on Friday from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, the same spot where, 57 years earlier, Martin Luther King Jr. had delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech. But his words were meant for all Americans.

“We need to have a conversation about your racism, about your bigotry, about your hate, about how you would put your knee on our neck while we cried for our lives.”

In the audience, tears spilled from Brantley’s eyes.

The social studies teacher from the Bronx organized two buses to travel from her neighborhood with 38 students and parents four hours to D.C. to stand here, shoulder to shoulder with them, and watch history unfold.

Her heart pounded in her chest as she listened.

Ever since a video of Brantley speaking to a local reporter during a Black Lives Matter protest in June went viral, she has collected more than $55,000 in donations to travel across the country to witness the protests herself. But coronavirus got in the way of those plans, so Brantley put her energy into planning this trip to D.C., the first time many of the children would be visiting the capital.

It was one of the few things that kept her going after her teaching contract wasn’t renewed for another school year, while she wondered how she’d feed her 8-year-old son or the times when the anxiety paralyzed her.

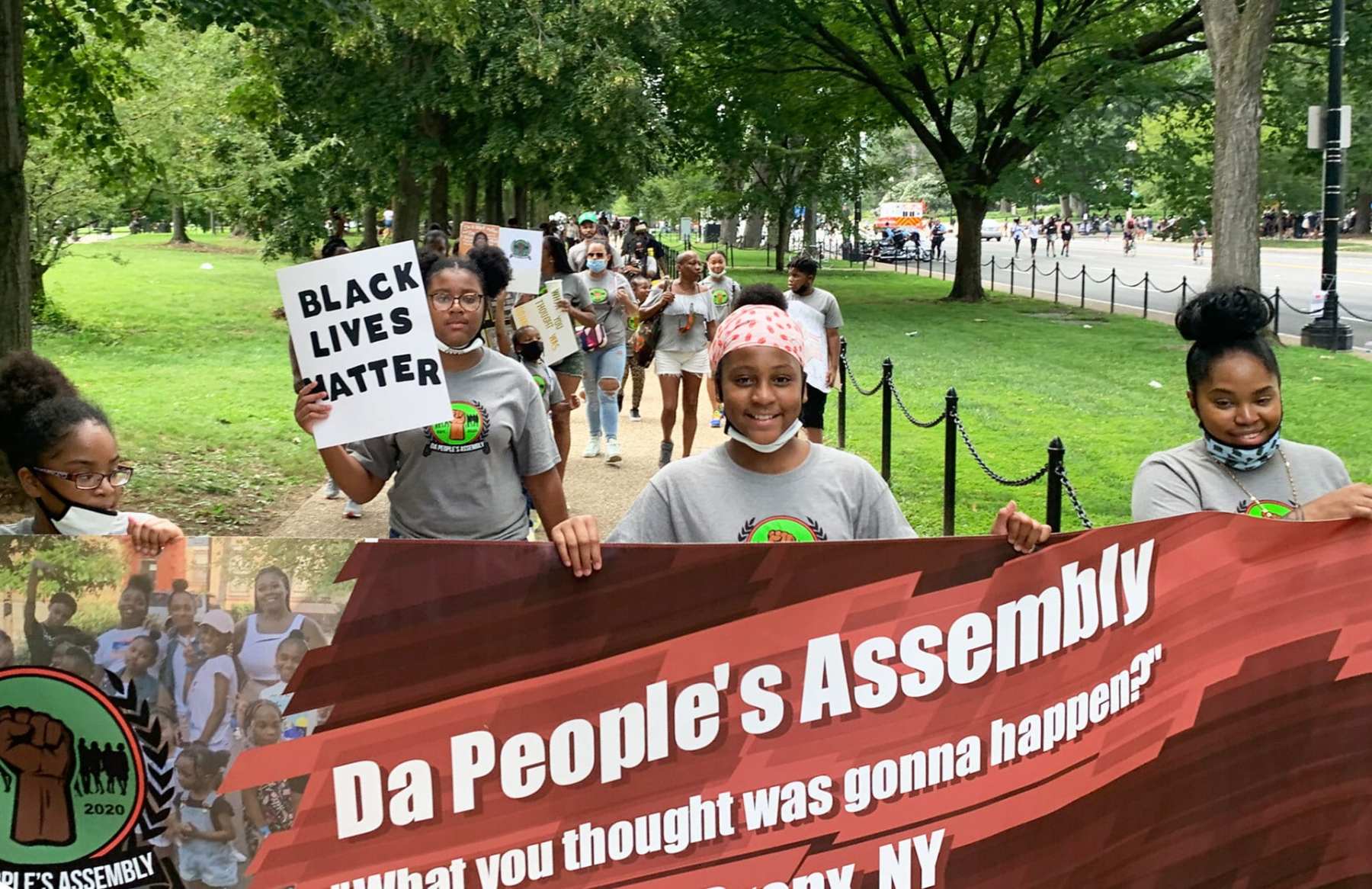

When Friday finally came, the assembled group set out early in the morning, before the sun peeked through the buildings in New York, all of them wearing gray shirts with the logo of a fist in the air and the name of Brantley’s organization, “Da People’s Assembly.” Brantley, 30, started the organization this summer to provide community activities for children of color who were interested in learning about social justice.

Some of them were young, elementary school-age kids who looked at the trip as a chance to leave New York. They marveled at the Washington Monument because it was bigger, they said, than it looked in the Spider-Man movie from three summers ago. They carried bright pink posters with “MY LIFE MATTERS” spelled out in marker and glitter.

As they walked through the throng of people, her son, Jesiah, asked, “Why can’t they understand we just want to live? Why do we have to march? Why do we have to make signs? Why can’t they just do what they’re supposed to do?”

Brantley didn’t have an answer right away. But another man walking by piped in: “You know why they don’t have the answer yet? Because you’re not up to the White House yet.”

The interaction was why Brantley had come to D.C. She wanted to feel hopeful again.

As she watched the kids spread out and eat their lunch on the lawn, Brantley tuned out the voices and took it in. The kids were making TikToks and cleaning after themselves. They were using teacher call-outs — “If you hear me, clap once!” — and chatting about what they’d do next time they were in town.

“It gave me that classroom experience I’ve been missing the last couple of months,” she said.

After sending applications out all summer, she has three job interviews this week for teaching and tutoring positions. It’s less than she used to make teaching middle school social studies, but it’s a start.

On the drive home, the energy in the bus was different. Something had clicked for the kids.

They spent the drive listing all the things they wanted do next: A fashion show fundraiser for Black Lives Matter, a trip to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in D.C., a promotional video done in the style of Marvel’s Avengers. Brantley could stand in the middle, they told her, and say “Da People’s Assembly assemble,” just like in the movie.

She laughed and promised to write down their ideas.

Before they arrived home, the group stopped at a rest stop on Interstate 95 named for Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden — the Biden Welcome Center, near Newark in Delaware. In line for Popeyes, Brantley spotted a face she had only ever seen before on TV: Korey Wise, one of the exonerated Central Park Five.

Wise, who spent 14 years in prison for a crime he did not commit, is now a civil rights activist. He had been at the march earlier that day.

“Mr. Korey Wise,” Brantley said, approaching him.

“I know you’ve been asked to take a lot of pictures,” she said, “you and I know how us New Yorkers are, once we get our cameras out, we ready to go.”

He smiled at her from under a black New York Yankees cap. “Where are you from?”

The Bronx, she told him.

“I could tell,” he said, agreeing to the photo.

Brantley then told him how her father and uncles had watched his case unfold. She told him she was a social studies teacher — “the real social studies, where I’m telling it from our perspective, our history.” And she introduced him to her activism work, to the group whose name she had printed on her shirt.

They were still “babies in the social activism world,” she said, but he seemed pleased.

Then her nephew Jarrid walked up.

“Are you Korey Wise?” the 13-year-old asked.

Wise and Brantley exchanged a look.

“Are you Korey Wise?” Wise responded.

“No,” Jarrid said, “but I could have been a Korey Wise.”