On Monday, at one end of the National Mall, Donald Trump will be sworn in for a second time as president after running a racist and misogynist campaign supported by half of American voters.

Monday marks a very different legacy, as well, that of Martin Luther King Jr., whose words and actions more than six decades ago on the opposite end of the Mall helped usher in a freer, more just and equal society for all Americans.

For only the third time in history, the King holiday will coincide with Inauguration Day. It’s a stark reminder of the duality of our democracy and the choices we can make about what to celebrate and who we want to be.

“What better day for this to occur than the King holiday, because that means now people get to see this major contrast,” said Bernice A. King, the civil rights leader’s youngest daughter and CEO of The King Center, the nonviolence institute founded by her mother shortly after her father’s assassination.

“Instead of being consumed with whatever that day is going to be about, from [Trump’s] perspective, people will also get an opportunity to hear about the real vision for our world that’s steeped in humanity and what it means to be a compassionate nation,” King said. “I think it’s great from that perspective and it gives people an outlet to do something on a day that could’ve been extremely challenging.”

On August 28, 1963, King stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, looking out onto the diverse crowd of faces stretching back toward the Washington Monument and positing that America had not yet made democracy real for all of her people.

“When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir,” King said. “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note. … But we refuse to believe the bank of justice is bankrupt.”

King urged his government to finally make America great and end the scourge of systemic racism. He spoke of the “fierce urgency of now” and a faith that could “hew out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.”

The latter phrase is among the words etched into the King Memorial that was dedicated in 2011, on the 48th anniversary of the March on Washington. The stone monument is carved into a statue of King, arms folded, staring intently across the Tidal Basin into the horizon.

It stands among memorials to the American presidents who have helped to frame our democracy and perfect our union, juxtaposed between the authors of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, and the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln.

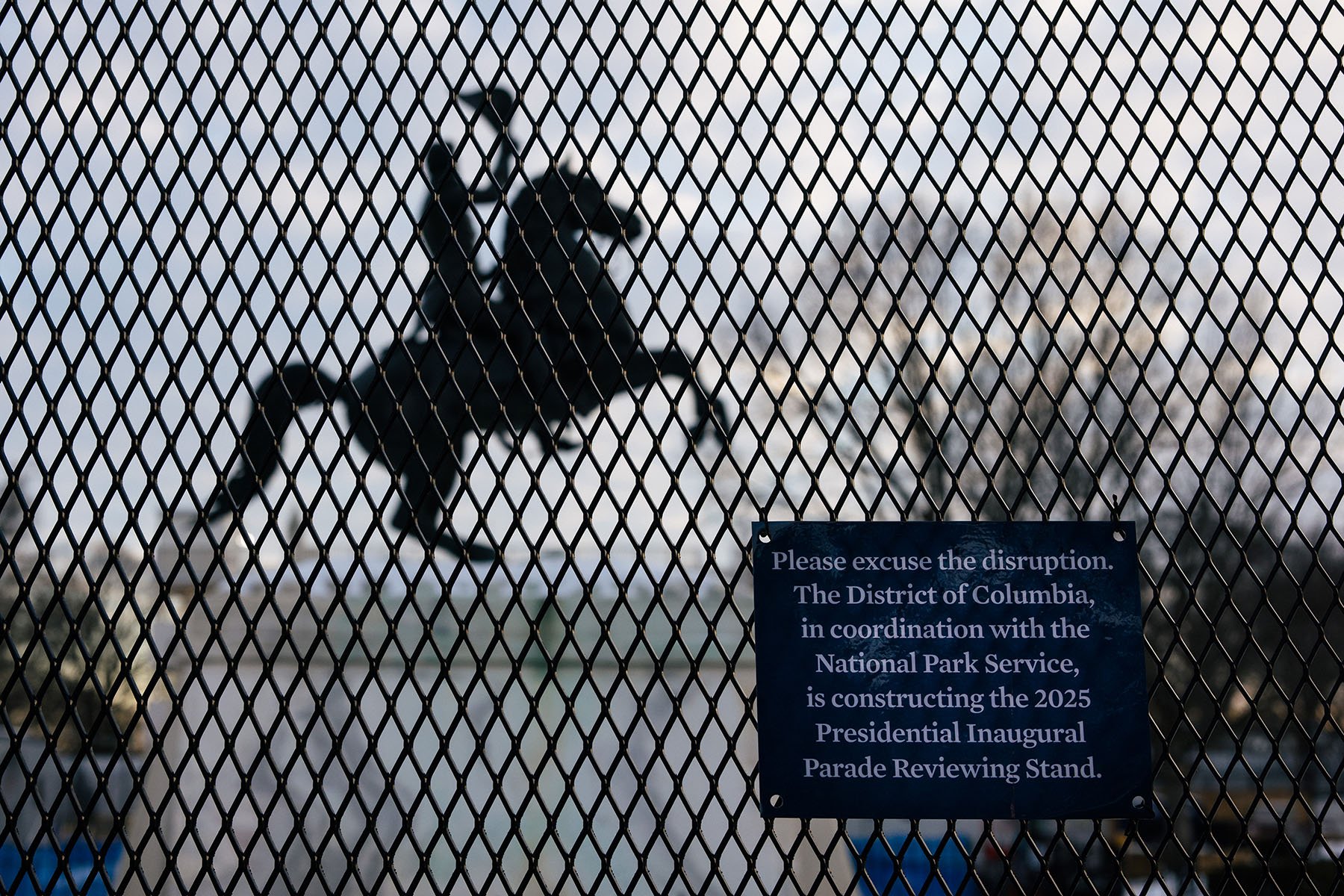

On a recent winter day in Washington, those words also seemed frozen, the barricaded Capitol in the distance a sign of caution at a time of uncertainty in our politics. As the sun rises on a chilly Monday in the capital, King’s words will share the spotlight with a president, both echoing across the National Mall and our two Americas.

Both Barack Obama and Bill Clinton — one born nearly a decade before the start of the Civil Rights Movement and the other born several years into the era, who went on to become the country’s first Black president — gave their second inaugural addresses on the King holiday, and both invoked King in their remarks.

In 1997, Clinton called King’s 1968 speech “words that moved the conscience of a nation,” and said King’s dream was the American Dream.

“His quest is our quest: the ceaseless striving to live out our true creed,” Clinton said. “Our history has been built on such dreams and labors. And by our dreams and labors we will redeem the promise of America in the 21st century.”

Obama wove King’s story into the American story of multiracial, multigendered social justice and progress, telling the audience: “We, the people, declare today that the most evident of truths — that all of us are created equal — is the star that guides us still; just as it guided our forebears through Seneca Falls, and Selma, and Stonewall; just as it guided all those men and women, sung and unsung, who left footprints along this great Mall, to hear a preacher say that we cannot walk alone; to hear a King proclaim that our individual freedom is inextricably bound to the freedom of every soul on Earth.”

Eight years ago in his first inaugural address, Trump called for the end of “American carnage” in his pledge to “Make America Great Again.” It was a message that sounded race- and gender-neutral, but in policy has targeted immigrants; restricted women’s access to reproductive care; demonized transgender Americans; and weaponized diversity, history and masculinity.

On Monday, he’ll take the oath of office in the building where he helped unleash carnage four years ago. After losing the 2020 election, Trump questioned the results — particularly in states where Black voters were crucial to Democratic victory — and encouraged his supporters to disrupt the election certification process at the U.S. Capitol. They did, in a violent attack that is a sharp contrast to King’s calls for nonviolence.

The title of King’s last book posed a question, “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?”

Many Americans will choose community on Monday, observing the King holiday through countless service projects that will address the kinds of issues King championed during his life, from housing, to poverty, to hunger.

His leadership persisted even in the face of opposition — a lesson for Americans living today, Bernice King said, adding that continuing to seek common ground on policy solutions should happen no matter who the president is.

The dichotomy between Trump’s and King’s actions will be on display far beyond Monday; how voters, elected officials and others respond to that gap will be the work of the next four years, not just one day.

King’s strategy of nonviolent resistance was also about collective action, which he called every American to join at the March on Washington.

Monday will be a reminder of the choice Americans made last year and the choices ahead of us, our nation’s ongoing struggle between chaos or community. That includes whether politicians try to heal the country or exploit divisions along lines of race, gender and nationality — whether, in the words of King, we “learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.”