In 1984, she was too new. In 2008, she was too inexperienced.

In 2020, will it be “third time’s a charm” or “three strikes, you’re out” for a woman vice president?

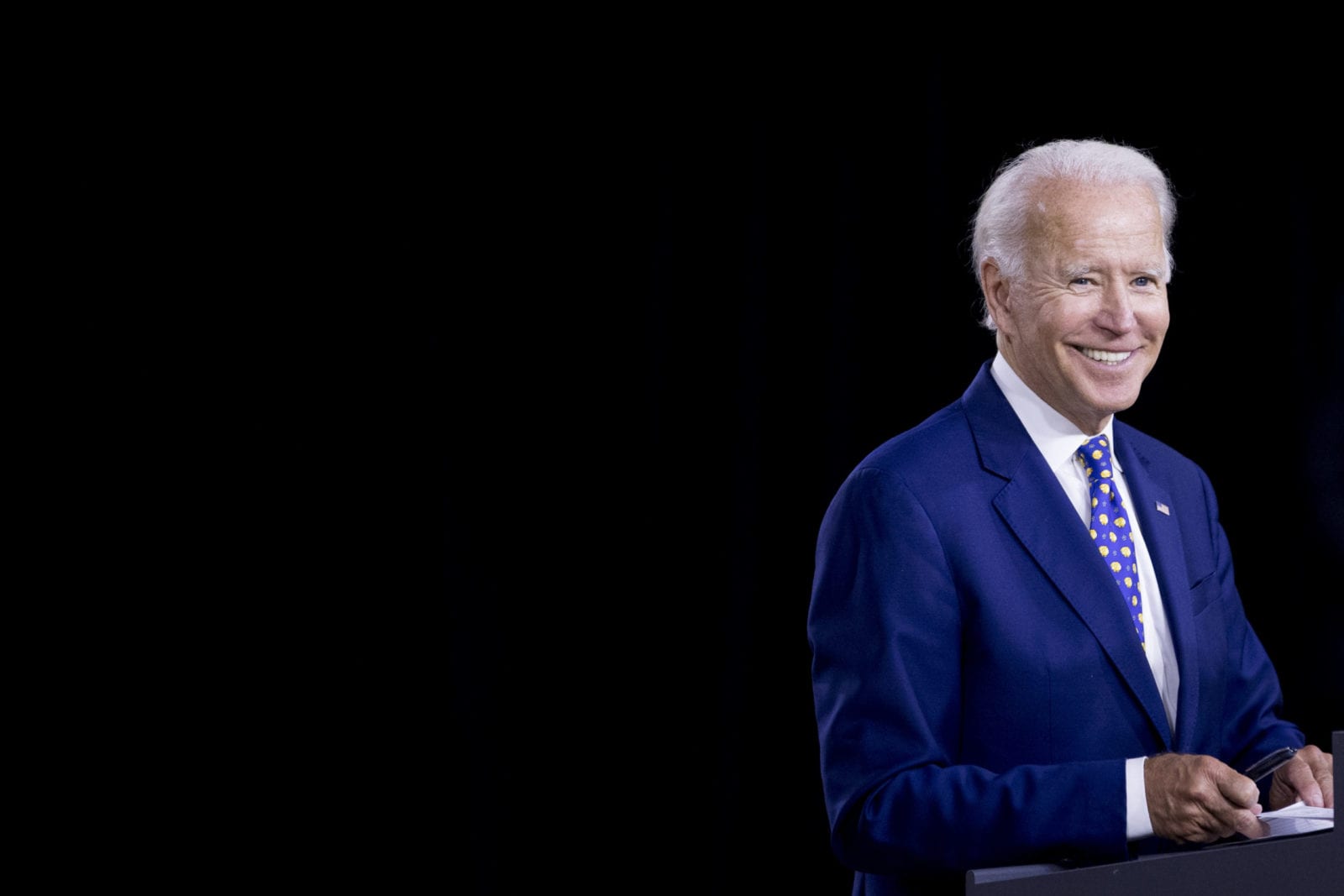

While still campaigning to become the Democratic nominee this spring, Biden pledged to choose a woman as his running mate, exciting the millions of voters who make up the majority of the electorate. The decision, which is expected to be announced as soon as this week, will take on outsize significance, not only because the pandemic has dried up the typical firehose of campaign news, but because of the hushed acknowledgement that this could be a legacy pick for the White, male septuagenarian.

“This is the moment we’ve all been waiting for,” said Donna Brazile, who was a 24-year-old staffer on Democrat Walter Mondale’s 1984 campaign when he chose U.S. Rep Geraldine Ferraro of New York as his running mate, putting a woman on the ticket of a major party for the first time. “We no longer have to knock on doors and encourage women to run; women are stepping up to lead. This feels different.”

The momentum for women in politics has been building for decades, it but took on an added sense of urgency in 2016, when Hillary Clinton made history as the first woman to be the U.S. presidential nominee of a major political party. It further swelled when the 2018 midterms ushered in the largest number of women ever elected to Congress, and California Democrat Nancy Pelosi — elected the first woman speaker of the House in 2007 — reclaimed the gavel.

In the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, it reached a crescendo: A record six women stood for the nomination, and while none broke through this cycle, they all sparked a conversation around the gendered coding in the term “electability,” the idea of selecting a candidate most likely to win the race.

But just as there has never been a woman president of the United States, there has never been a woman vice president — which brings us to this moment. In a year that marks the centennial of women’s suffrage, honoring the ratification of the 19th Amendment, this election presents an opportunity to again make history.

The stakes for the vice presidency seem higher than they’ve ever been, and Biden’s choice could influence what and who we perceive as presidential, said Kelly Dittmar, director of research at the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University.

“The implications of that are that citizens might stop questioning as much the ability or qualifications of women for presidential office,” Dittmar said. “If she’s already in this office and second in line to power, does that change biases around whether a woman can or should do the job, or whether she could win an election? That’s part of the impact.”

Only two women have ever been chosen as running mates for the two major parties: former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, the unconventional and calamitous pick by Republican John McCain in 2008, and Ferraro in 1984.

“In 1984, it sent a message to women that things are possible, that there is a place for them in the executive office, and that gave them hope,” said Alyssa Mastromonaco, who was part of the vice presidential selection process for Democratic nominees John Kerry in 2004 and Barack Obama in 2008.

“Since it was the first time, people understood when it didn’t happen, but now, this is it,” Mastromonaco continued. “There’s a feeling that this woman has to be the woman that gets it across the finish line — otherwise, the story is that a woman couldn’t get it done again.”

Vice presidential candidates rarely prove an effective victory strategy — the conventional wisdom around the selection is “do no harm.” Rather, they are often discussed in terms of what they can bring to a campaign: battleground or swing state appeal, enthusiasm, connections to key constituencies.

Biden’s purported short list has included a diverse number of talented, capable and qualified women for the role, from mayors and governors to senators and those who had never held statewide or even elected office. Among them are at least four Black women: Sen. Kamala Harris, former National Security Advisor Susan Rice, and Reps. Karen Bass and Val Demings.

As Brazile notes, that’s a sea change from a generation ago, when women like Shirley Chisholm, the first Black candidate for a major party’s nomination and the first woman to seek the Democratic Party’s nomination in 1972, lamented that no Black women were in contention for the No. 2 slot.

The call for a Black woman on the ticket has grown louder amid the national reckoning on race, as some voters and observers say Biden needs someone whose lived experience reflects the current social and political moment — and who can help to unite the country.

“We’re at that inflection point that everyone continues to talk about, where the country is ready to turn the page, with not just a woman, but also perhaps a Black woman,” Brazile said.

To choose a Black woman as his running mate, which would also be a first, means more than the promise of a Supreme Court or cabinet nomination — decisions that are essentially recommendations. For many Black women voters in particular, picking a Black woman to join him on the ticket is a signal that Biden recognizes the contributions of the most loyal and consistent voting bloc in the Democratic Party.

“I do think it matters to have someone on the ticket that sends a message to people that this woman looks like America,” Mastromonaco said. “That’s something Trump’s ticket is never going to do. And what they have to show is utter competence, by having someone on the ticket who is deadly serious and has proven they can lead and manage. It’s a bigger deal than ever before, because, literally, the public health is in the balance.”

The election was already considered by many to be the most consequential in modern politics, but 2020 has taken on an added sense of urgency with the dual pandemics of coronavirus and systemic racism. If elected, Biden and his governing partner face the challenge of healing the country on multiple fronts.

Regardless of his decision, the woman who could become vice president will contribute to the progress of all women in politics, said Dittmar.

“This was overdue,” she said. “Women have been the heart of the Democratic Party, which claims to value inclusivity. It will become increasingly hard for a Democratic nominee to present an all-male, all-White ticket to the public.”